- 524 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Population and World Food Supplies

About this book

Originally published in 1954. This great work surveys the distribution of the world's population and the food production of all countries chosen as important by reason of either their demands on the world food market or their contributions to it. The author concludes that the more advanced countries can be reasonably assured of food supplies for an indefinite period. The less advanced countries can no longer rely on self-contained systems: they must seek co-operation with the advanced countries to supply them with the appliances needed for a more highly developed agriculture. This book at the time gave statesmen and their scientific advisers, agriculturalists and agricultural economists an invaluable new instrument.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Population and World Food Supplies by E. John Russell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 11

THE FOOD EXPORTERS: I. THE UNITED STATES, CANADA

The United States

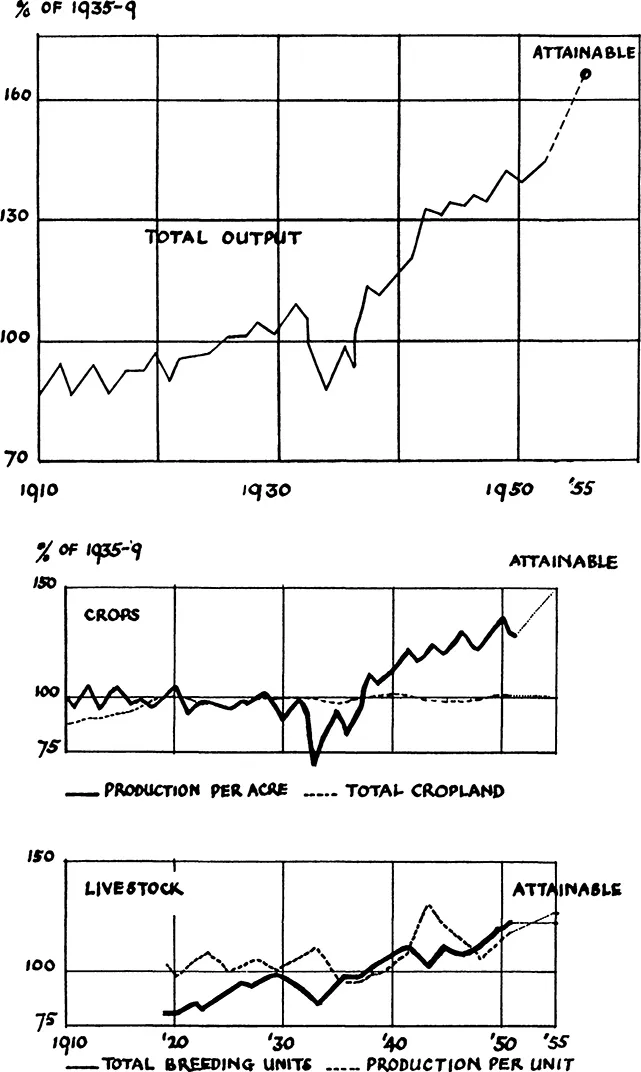

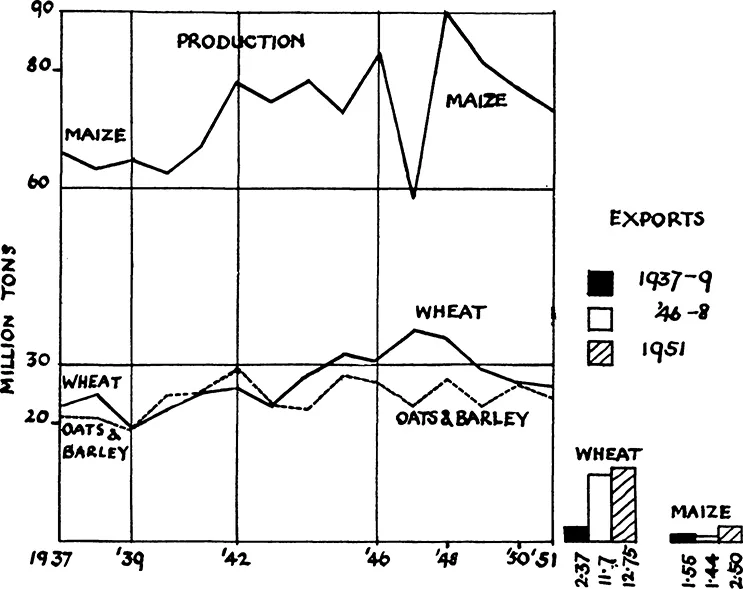

The agriculture of the United States may be regarded as a major balancing factor in making up the food supplies of the free world. It is remarkably flexible, and the great development of industry and the ease of transfer from one activity to another, together with the ingenuity of the farmers and of their advisers, make expansions and contractions much easier than in most other countries. The late 19th century and the early years of this century saw a large expansion of output from the farms and ranches; between 1900 and 1904 it rose by 42 per cent to a value of nearly $5 thousand million: an “unthinkable aggregate” as the Secretary to the Department of Agriculture put it.1 Yet the curve of production has steadily continued to rise, broken only by years of severe drought—especially 1934 and 1936—and still further output is anticipated (Fig. 17). But the position in regard to exports has changed a good deal. The early period had been one of large export of grain, especially wheat, and also of meat, at prices which, though very favourable to an industrial population, put many of our farmers out of business. They were, of course, equally unattractive to the American farmers. Fortunately their home demand was expanding greatly with the enormous development of industry, and so exports fell off rapidly from 1920 to 1932 and remained at a low level till 1944 when they rose rapidly (Fig. 18).2 Other food exports followed a similar course.

The needs of the allies during the war, however, and the distressful condition of Europe after the war, aroused deep sympathy, and tremendous efforts were made to increase food production. Output of grain was almost doubled, giving large surpluses for export, while the production and export of bacon, pork and lard increased so much that there was now an overall export surplus of meat instead of a net import. Large quantities of eggs, milk products, vegetables, potatoes and dried fruits were exported also. More significant still, the output of oil seeds, especially soya bean, increased so greatly that the United States instead of competing with a hungry Europe for African vegetable oil actually became an exporter—a position which if it is maintained will profoundly affect the supply of margarine for the European countries. The only foods imported on any large scale were sugar, certain fruits and canned fish.

1 Rpt. Sec. Dept. Agric., U.S.A., Washington D.C., 1904.

2 From Foreign Agricultural Situation, p. 21.

Perhaps even more important than the export of food has been the devising of new methods, especially combinations of methods, and appliances for solving difficult agricultural problems. The knowledge and experience gained is freely put at the disposal of other countries and has been widely drawn upon for dealing with such serious difficulties as soil erosion, salt and alkali troubles on irrigated land, mechanization and other problems.

FIG. 17. —Expansion of agricultural output in the United States: pre-war to post-war period (from Ag. Information Bull. No. 88, U.S.D.A. 1952).

FIG. 18. —Production and exports of grain. U.S.A. 1937-1951 (data from C.E.C. Reports, Grain Crops, 1953, and from F.A.O. Stat. Year Book, 1951).

The great expanse of the country and the wide range of climatic conditions allow the growth of practically all crops, but large home markets—and also the psychology of the American farmer—favour standardization and economy of working, and in consequence there is much specialized farming, based, however, on its suitability to the conditions. The result is a highly complex agriculture which I shall not attempt to describe, nor is this necessary as it has been so fully done before.1

1 See especially the Year Books of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture.

The hundredth meridian which runs from the Mexican border through Omaha to the Dakotas divides the country into two great divisions: the mountainous region of the west, and the great plains of the centre and the south, broken in the east by the Appalachian mountains. The rainfall in the eastern regions is good and well distributed, but farther west it is less and there may be long periods with little or none; the mountainous west has great areas of desert. The greater part of the cropping is in the eastern division. The climate of the north-east—the New England States and the lake region— is something like that of Great Britain except that the winters are much colder and their coming and going more abrupt: this is a region of grass and fruit trees; much dairying is practised here and also in Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota in the lake region. The north-central region includes the wheat-growing States of the Dakotas and east Montana; farther to the south is another block of wheat-growing country in Kansas, Oklahoma and north Texas; in between comes Nebraska where wheat is less important. The main central region is the maize belt, but the farmers early learned the advantage of selling the corn as meat, and much animal husbandry is practised for which other feed grains and forage are grown also. Store cattle are bought from the west, fattened, and sent to Chicago and other packing centres; large numbers of pigs are raised also. Many of the farms are very productive. This region includes much of Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana and western Ohio. In the east central region, including the Virginias, Kentucky, Tennessee, there is more general farming, including tobacco growing, and to the south is the great block of cotton-growing States stretching from South Carolina to Louisiana. The remarkable peninsula of Florida is largely horticultural.

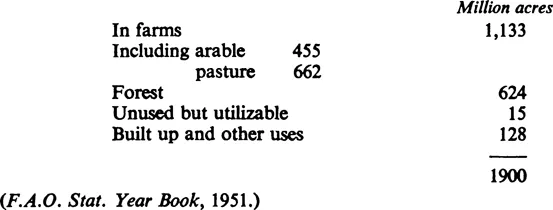

The total land area is 1,900 million acres, but of this only about 60 per cent is farmland and less than half that is described as “improved.” The utilization is as follows:

The farmland rose from 987 million acres in 1930 to 1,141 milhon acres in 1945 as the result of the increasing demand for food, but some of this area proved unsuitable and has been abandoned.

The farmland was in 1950 divided into 5,384 holdings; for some years the number has been falling and the average size of the farms increasing:

1930 | 1940 | 1945 | 1950 | |

Number of farms, millions | 6·289 | 6·097 | 5·859 | 5·384 (1) |

Average size, acres | 157 | 174 | 199 | 210 |

Farm population, millions | 29·45 | 29·05 | 24·34 | 24·43 |

(1) About 200,000 of the fall in number since 1945 is due to a change in definition of a farm.

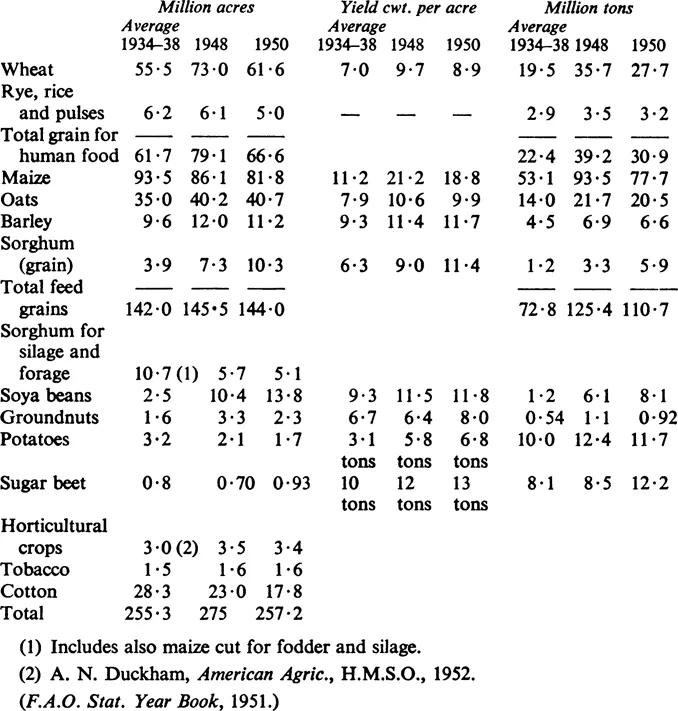

Of the 455 million acres classed as arable land, about 255 million were in the chief tillage crops before the war; this was raised to 280 million acres for a time after the war but has since returned to its old level. The areas and production of the principal crops are given in Table LXXXVIII. The remaining arable land (about 200 million acres) is taken up by fallows, rotation grasses and various other crops: the total for the 52 principal crops was in 1950, 339 million acres, but this was lower than in any year since 1941. There are no fodder root crops1 or kales, and folding in the English sense is not done.

TABLE LXXXVIII. Areas and production of chief crops, United States

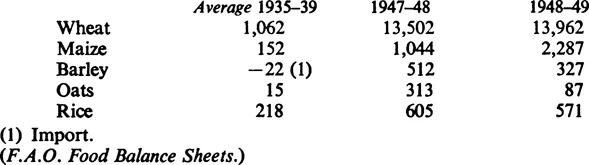

Striking changes in area and output of the chief crops resulted from the war and post-war food situation. Twenty million acres were added to the area of tillage crops in 1948 and 5 million acres formerly in cotton went into food crops; in 1949 a further 5 million acres of land was brought in to restore the cotton acres without trenching on the area of food crops. The production of wheat and of maize went up by more than 80 per cent and the net exports were, in thousand tons:

1 This absence of root crops has long been characteristic of American agriculture. When Sir Henry Gilbert visited the States in 1882 he expressed surprise that such useful crops should not be grown but he adds: “I was told that no American would bend his back to hand hoe.”

The great increase in production which made these huge exports possible had resulted partly from increased acreages, but partly, and in the case of maize entirely, from increased yields per acre: a new feature in American agriculture. Yield statistics go back to the 1870’s: they showed little change till the mid-1930’s, improvements in some directions being offset by deterioration in others.

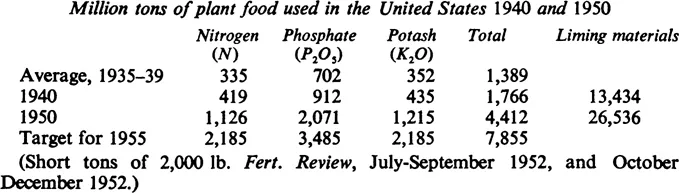

Among the chief factors in bringing about these recent increases in yields have been the use of improved varieties, of better cultural practices, the greatly increased consumption of fertilizers which more than doubled between 1940 and 1950:

It is estimated that much more fertilizer could be used with advantage, and a high target has been set for 1955. The United States is self-contained for nitrogen and phosphate, having immense deposits of rock phosphate estimated at 13-3 thousand million long tons.1 Fertilizers are used most extensively in the eastern half of the States, especially east of the line joining Chicago and the Mississippi delta. Little has hitherto been used in the wheat belt, but more is now being applied.

American farmers are very ready to adopt drastic chemical treatment against pests and diseases.

Another important factor in the increased production has been the spread of more prolific varieties. The new hybrid maize and sorghum varieties in particular have proved remarkably successful, giving 25 per cent or more higher yield than the old ones. Moreover, their value is not confined to the United States: already they or others obtained by similar methods have proved useful in other countries also.2

1 Fert. Rev., April-June 1952.

2 For an account of hybrid maize see E. S. Bunting, World Crops, 1950, Vol. 2, p. 5.

Neither fertilizers nor improved varieties could have been fully effective without the recent great increase in mechanization. The number of tractors rose from 2-21 millions in 1944 to 3-94 millions in 1951, and special implements were widely used for particular purposes such as lifting of sugar beet even when their use involved some reduction in plant population. The resulting increased speed of working ensured better sowing conditions in the short spring and reduced harvest losses in the short autumn. There are of course fewer horses on the farms; the number fell from 10·6 millions in 1939 to 4·8 millions in 1951, and of mules from 4·2 millions to 2·0 millions: incidentally liberating some 55 million acres previously used for growing their food. But the farmer has become almost completely dependent on petrol coming from outside the farm instead of supplying his own power as before, and it is impossible to foresee what might happen if troubles come.

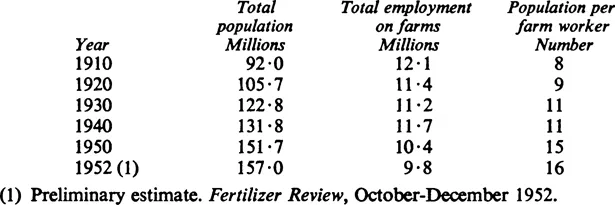

As a result of these various improvements there has been a great increase in output per man-hour which has gone far to counteract the drift from the land that has been so pronounced since 1941: the farm population, which had then been 29 millions, having fallen to 24·4 millions by 1950, and the total number of workers fell from 11·7 millions in 1940 to 10*4 millions in 1950 and still fewer in 1952 (Table LXXXIX).

TABLE LXXXIX. United States Population and total employment on U.S. farms

Their ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Illustrations

- I The Problem: Feeding the World’s Population

- II The United Kingdom. Eire

- III Methods of Increasing Food Production

- IV Northern Europe’s Intensive producers: The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Finland

- V France; the peasant producers of the Mediterranean lands: Spain, Portugal, Italy, Israel, Egypt

- VI Africa’s Southern Regions: the White Man’s Farming

- VII Africa: the Central Regions: Eastern Group; African Peasant and European Farming

- VIII Africa: the Central Regions: Western Group; African Peasant Farming

- IX Asia. India and Pakistan; Problems of Growing Population

- X Asia. China, Japan, Indonesia and the Rice Exporting Countries

- XI The Food Exporters: (1) The United States, Canada

- XII The Food Exporters: (2) Australia, New Zealand

- XIII Potential Suppliers: the South American Countries

- XIV Trends in Food Production

- LIST OF FIGURES

- INDEX