- 134 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Twenty years after Gordon Sturrock and the late Professor Perry Else's 'Colorado Paper' introduced the Play Cycle, this theory of play now supports professional playwork practice, training and education. The Play Cycle: Theory, Research and Application is the first book of its kind to explain the theoretical concept of the Play Cycle, supported by recent research, and how it can be used as an observational method for anyone who works with children in a play context.

The book investigates the understandings of the Play Cycle within the playwork field over the last 20 years, and its future application. It addresses each aspect of the Play Cycle (metalude, play cue, play return, play frame, loop and flow and annihilation) and combines the theoretical aspect of the Play Cycle with empirical research evidence. The book also provides an observational tool for people to observe and record play cycles.

This book will appeal to playworkers, teachers, play therapists and professionals working in other contexts with children, such as hospitals and prisons. It will support practitioners and students in learning about play and provide lecturers and trainers with a new innovative teaching and training aide.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

A review of the Play Cycle

Introduction

A (very) brief overview of the ‘Colorado Paper’

Playwork and playworkers

- All children and young people need to play. The impulse to play is innate. Play is a biological, psychological and social necessity, and is fundamental to the healthy development and wellbeing of individuals and communities.

- Play is a process that is freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated. That is, children and young people determine and control the content and intent of their play, by following their own instincts, ideas and interests, in their own way for their own reasons.

- The prime focus and essence of playwork is to support and facilitate the play process and this should inform the development of play policy, strategy, training and education.

- For playworkers, the play process takes precedence and playworkers act as advocates for play when engaging with adult led agendas.

- The role of the playworker is to support all children and young people in the creation of a space in which they can play.

- The playworker’s response to children and young people playing is based on a sound up to date knowledge of the play process, and reflective practice.

- Playworkers recognise their own impact on the play space and also the impact of children and young people’s play on the playworker.

- Playworkers choose an intervention style that enables children and young people to extend their play. All playworker intervention must balance risk with the developmental benefit and well being of children.(PPSG, 2005)

The six elements of the Play Cycle

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 A review of the Play Cycle

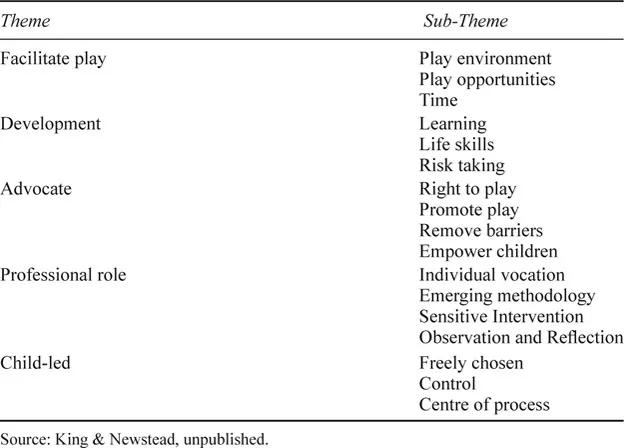

- 2 Playworker’s understanding of the Play Cycle

- 3 Beyond the intrinsic

- 4 Transactional analysis and the ludic third (TALT): a model of functionally fluent reflective play practice

- 5 The Play Cycle Observation Method (PCOM)

- 6 Conclusion

- References

- Index