- 426 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Empirical Poverty Research in a Comparative Perspective

About this book

First published in 1998, this books considers defining the concept of poverty as a collective issue through an empitrical view point on an international scale. Looking to define 'poverty' by compiling case studies by academics writing from viewpoints in a variety of individual countries.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Empirical Poverty Research in a Comparative Perspective by Hans Jurgen Andreß in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Economic Conditions. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Conceptual issues

Rethinking poverty in a dynamic perspective

Robert Walker

This chapter begins with the sociologically familiar, moves on to consider the less familiar and concludes with the as yet unknown. In doing so, the aim is to contribute to the understanding of the nature of poverty, while simultaneously making links of both a theoretical and substantive nature with other chapters in this volume.

Throughout the paper judicious use is made of the statistics and experience of a number of different countries. Except in rare instances, direct comparisons are not intended nor should it be inferred that poverty is precisely the same everywhere irrespective of social context. On the other hand, there are some eternal verities which are the logical consequence of specified assumptions and others which relate to the shared experience of being poor.

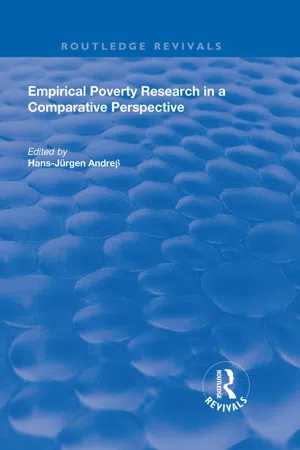

1 Questioning old style poverty measurement

Commencing with the familiar, Figure 1 presents now quite old Eurostat data on the incidence of poverty in Europe in the first half of the 1980s. The measure of poverty used is based on income and, being set at 40 per cent of the European Community average, is severe. The diagram reveals that at that time poverty was much lower in the geographical and economic core of Europe and falling, and higher and rising in the peripheral areas. (The reasons for this pattern fall beyond the scope of this chapter but possibly reflect the restructuring inherent in the increasing economic integration of Europe (Cross 1993).)

Figure 1 Individuals with income below 40 per cent of community average (1980–85)

Source: Commission of the European Countries 1991

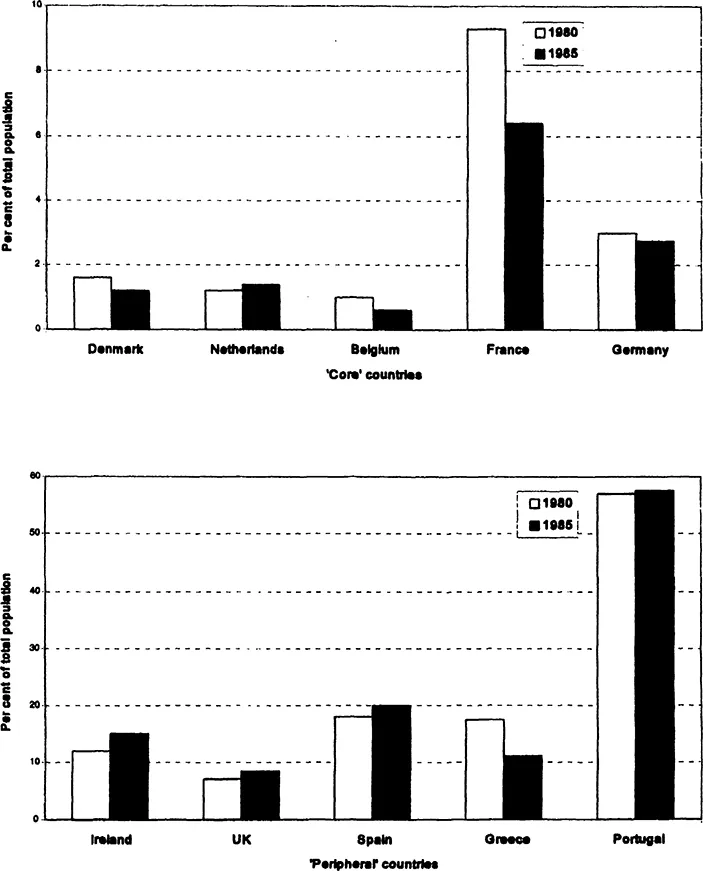

Figure 2, which unfortunately excludes Germany takes an expenditure based measure for 1988 with poverty thresholds set at 50 per cent of national household expenditure. Despite the difference in definitions,[1] the statistics show broadly the same geographical pattern. Moreover, as can be seen from Figure 2, the incidence of poverty was noticeably higher among women than among men, especially in the European periphery.

Figure 2 Poverty* in risk groups for Euro II (1988) - female headed

* Defined as 50 per cent of national average equivalent expenditure

Source: Eurostat 1991

Source: Eurostat 1991

These statistics are not without substantive significance and were very important politically: the furore that these and similar figures provoked in certain countries led to the erasure of the term ‘poverty’ from the European political lexicon (Room 1995). However, they reveal very little about either the nature or distribution of poverty. That this is so can be illustrated by the following thought experiment. Imagine an intelligent Alien visiting Earth with a mission to learn about poverty; and consider the questions that such a creature would ask. One could expect at least the following:

- What is the nature of poverty, what does it mean to the people who experience it?

- How many experience it?

- How long does it last?

- How severe is it?

The fact that Figures 1 and 2 contain insufficient information with which to answer this basic set of questions is not in itself surprising. More telling is the difficulty of identifying any study that contains answers to all of these questions and the small number of studies that ever address the issues of severity and duration. Moreover, as we shall show below, failure to answer a single one of these questions means that the answers given to at least two of the others will be partial and potentially misleading.

If the Alien had a truly investigative frame of mind it might also be expected to ask ‘What causes poverty?’ and even ‘What can be done about it?’. The remainder of this chapter touches briefly on each of these questions, though not quite in the same order. Readers more accustomed to taking a static rather than a dynamic view of poverty might expect the definition or meaning of poverty to be discussed ahead of measurement. However, a direct consequence of making time explicit in the measurement of poverty is to trigger a reappraisal of conventional assumptions about the nature of poverty.

2 Measurement: How many poor people are there?

Poverty is usually defined in terms of a shortfall in resources relative to a legitimate set of needs. Clearly much has been written about the appropriate definitions of resources and needs although the debate about the rights and wrongs remains vigorous (Citro and Michael 1995; Poverty Summit 1992; Bradshaw 1993). Less has been said about the choice of the accounting period over which resources and needs are measured, although this can radically affect the recorded level of poverty.

2.1 The accounting period

Lengthening the accounting period has the effect of reducing the cross-sectional poverty rate. This happens because averaging over time evens out the temporary mismatches between income and needs, lessens the degree of dispersion in the population and, hence, reduces the proportion of individuals appearing in the tails of the income to needs distribution. The consequences of changing the accounting period can be considerable and depend on the stability of people’s needs and the volatility of income flows. Measures of poverty will be more sensitive to the choice of accounting period in situations where circumstances are less stable. Given the recent development of a flexible labour market across Europe creating more precarious employment, one can presume that measures have become increasingly susceptible to the choice of accounting period.

As the accounting period is extended so the resultant estimates of poverty asymptotically approach the level of permanent poverty. This is because the shortfalls in income received by people who experience the shortest spells of poverty are the first to be offset by the higher income received during more prosperous periods. Also, the longer the accounting period, the more the characteristics of people counted as poor reflect those of persons who are in the midst of a very long spell.

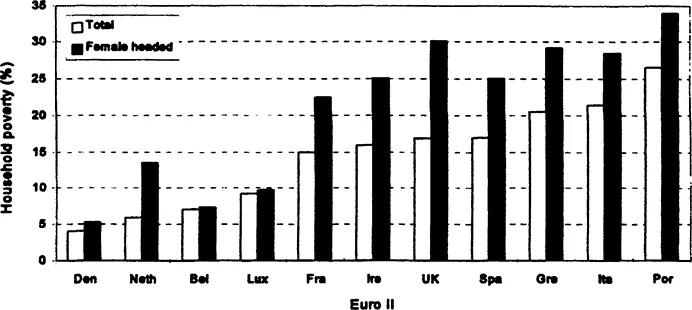

Figure 3 Annual and lifetime incomes in Great Britain

Source: Falkingham and Hills 1995

An example of this phenomenon comes from Britain and contrasts annual incomes with life time incomes based on a dynamic simulation model (Falkingham and Hills 1995). Consistent with theory, Figure 3 reveals that income measured over the life-time is much more egalitarian than annual income; indeed depending on the measure used, inequality is reduced by between a third and a half. Employing precisely the same data, and fixing an individual poverty line at 50 per cent of median income, causes the poverty rate to be approximately halved.

While there is probably no correct choice of accounting period, the choice makes a real difference. Various measures may need to be applied reflecting die purposes of the enquiry.

2.2 Prevalence

Thus far, we have focused on cross-sectional or static measures of poverty where assumptions about time are typically implicit. However, the assumptions need to be made explicit if a more dynamic view of poverty and social exclusion is to emerge. Moreover, with the advent of longitudinal data, additional decisions have to be taken concerning the period over which poverty is to be observed. A key concept, here, is ‘prevalence’: the proportion of a population that experiences a spell of poverty during a given period. This is the longitudinal equivalent of the cross-sectional poverty rate and suffers similar limitations. Prevalence is very sensitive to the length of the observation period; recorded values increase as the observation period is extended because of the enhanced opportunity to observe a greater proportion of short-term poverty.

However, this sensitivity offers a powerful tool for investigating the nature of poverty and for making comparisons between different countries or regions. If recorded prevalence rises linearly and rapidly as the observation period is increased, this indicates that poverty is principally experienced in short spells by different people. On the other hand, if prevalence is insensitive to extending the observation period, poverty is mainly long-term.

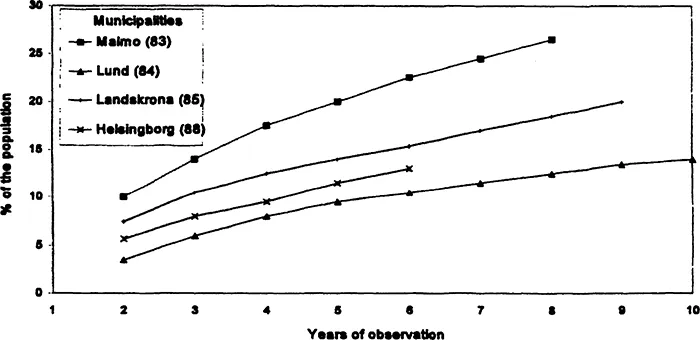

Figure 4 Percentage of population receiving social assistance in four municipalities in Sweden*

* The observation period for Malmo is 1983-89, for Lund 1984-92, for Landskrona 1985-92, and for Helsingborg 1988-92

Source: Salonen 1993

Source: Salonen 1993

Prevalence, therefore, has value as an analytic concept as well as a descriptive one and this can be illustrated with Swedish data on social assistance receipt Figure 4 arrays the numbers of people recorded as ever having received social assistance in four Swedish municipalities when the observation period is expanded from one to nine years. It shows that, depending on die locality, between four and ten per cent of people of working age make a claim for social assistance in any particular year, which is consistent with the widely accepted view that poverty in Sweden is comparatively rare and that social assistance fulfils a largely residual function. However, the fact that anywhere between 14 per cent and 28 per cent of the working age population will make a successful claim on social assistance in the longer term acts as an important corrective to the initial assumption. Moreover, it is evident that while the proportion claiming benefit is lower in Lund than in Malmo, people tend to receive benefit for a longer time (the slope of the curve is flatter).

The positive slope of the lines in Figure 4 reflects the fact that prevalence measures of poverty almost invariably exceed incidence; the number of households that ever suffer poverty often far exceeds the number in poverty at any particular time, a fact that politicians with a mission to dismantle welfare might do well to remember.

3 The meaning of poverty

Making time explicit, and focusing on the concept of prevalence rather than incidence, serves to remind us that the way in which poverty is distributed over time is related to the distribution of poverty within a population. This, in turn, helps to shape the experience of being poor and to mould its personal and social significance.

Given a fixed observation period, prevalence is determined by the total duration of poverty in the society, the length of spells and the degree to which the spells are recurrent. A lower boundary is set by the situation where the same group of people is continuously in poverty. The upper boundary describes the situation where poverty approaches a once in a life time event and where spells of poverty are as short as the global sum of poverty allows. Values in between imply that a variable proportion of the population is experiencing repeated spells of poverty of varying lengths.

Traditional discourse on poverty has implicitly assumed the kind of poverty associated with minimum, or at least minimal, prevalence. The poor have tended to be contrasted with the non-poor as if the two groups never changed places, that is as if the poor were permanently poor. Certainly, this concept underlies the rhetoric concerning the supposed growth in long-term dependency on benefits and is implicit in much of the discussion on social exclusion and the underclass (Deacon 1996). Indeed, other things being equal, the circumstances that foster the development of an underclass are most likely to arise when prevalence is low. Low prevalence suggests that that the poverty is experienced in long spells by a small number of people. As a consequence, poor people face low expectations of ever escaping poverty and come to have little in common with the wider society from which they are permanently excluded. Because the poor rarely change places with the non-poor, the lack of hope experienced by the former is matched by the latter’s ignorance of any personal experience of poverty. Moreover, since low prevalence generally means that those who are not in poverty face little risk of ever becoming poor, they are likely to have little concern for poor people or policies to help them. (Self interest is arguably a powerful motivator of apparent altruism.)

Figure 5 Static and dynamic poverty

* 50 per cent of the median equivalised income

Source: Duncan et al. 1995

Source: Duncan et al. 1995

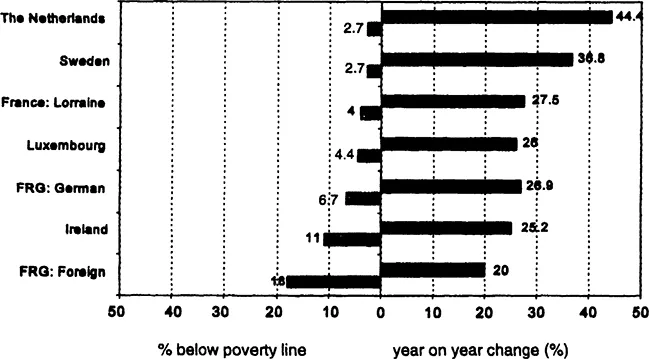

However, the reality is often very different as is indicated by the graph presented in Figure 5. This compares poverty rates for selected European during the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the threshold set at 50 per cent of median national equivalised income. But, more important in the current context, the graph also records t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Empirical poverty research in a comparative perspective: Basic orientations and outline of the book

- Part One: Conceptual issues

- Part Two: Methodological issues

- Part Three: Using a multidimensional concept of poverty: Results from different countries

- Part Four: Applying the dynamic approach

- Part Five: Problems of poverty research: Lessons from Italy and Russia

- List of contributors