![]()

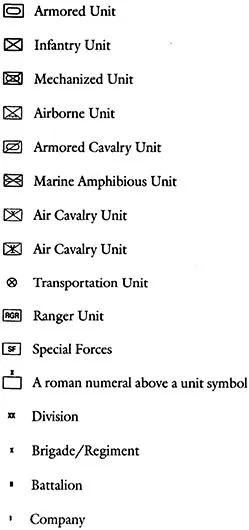

Symbols Used in Figures

Desert Storm

![]()

1

An Unexpected War

At 9:30 P.M. on Wednesday, January 16,1991, the pilots and aircrew of the U.S. 48th Tactical Fighter Wing were receiving the orders that would send them to war.1 Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein had ignored the United Nations ultimatum to leave Kuwait, and the military forces of the coalition arrayed against Iraq were preparing to push him out by force. Flying big F-lll fighter-bombers and electronic warfare planes, the 48th consisted of units based in England and Idaho, transferred to the Gulf to fight in a war no one had expected. Senior officers of the 48th briefed the squadron on its mission; across the whole front, a massive air assault on Iraqi forces and command centers was about to begin.

At 1:20a.M. on January 17, Saudi time, the F-llls—over 70 feet long and with 60 feet of wingspan—took to the sky, their turbofan engines glowing brightly in the dark of a moonless Gulf night. On their way to attack Iraqi air bases, the fighter-bombers were accompanied by other aircraft equipped to jam and suppress enemy radar and other electronic equipment. The squadron was also supported by old F-4 fighters carrying antiradar missiles whose mission was to attack Iraqi antiaircraft and radar sites.

More than 60 F-11 Is crossed the Iraqi border at over 600 miles an hour, flying low—200 feet or less—to avoid being picked up on Iraqi radar. By 3 A.M., the coalition attack was well under way throughout the theater. On reaching their target, the F-llls climbed rapidly to 5,000 feet and engaged their "Pave Pack" systems—a combination laser and infrared television camera used to mark targets. Similar equipment would soon provide many of the stunning images of the war: videotapes of bombs crashing into Iraqi command posts or hitting the front doors of aircraft hangars. Weapons system operators (WSOs) sitting in the F-llls looked into their viewers and picked out targets, designating them with laser-guidance beams.

The Iraqi defenders were wide awake and aware of the attack, and soon F-111s detected the search radars of surface-to-air missiles. The F-4s swung into action, shooting high-speed antiradar missiles (HARMs) to silence the Iraqi positions. Deadly streams of antiaircraft gunfire reached up to the U.S. planes. The Iraqis were trying desperately to knock them out of the sky before they delivered their ordnance—accurate laser-guided bombs, thousands of pounds of them on each aircraft. The WSOs dropped their bombs and watched as targets exploded—weapons storage bunkers, maintenance hangars, aircraft shelters.

Most of the planes were over Iraqi airspace for about forty minutes, flying 200 or more miles inside hostile territory. The sky, the pilots reported on their return, was filled with coalition aircraft. This first night over 2,000 "sorties"—individual attacks by coalition aircraft—were flown.

On the squadron's return, a reporter noticed a unique shoulder patch being worn by one of the squadron's pilots. Bearing a crude image of the F-111, it had been designed especially for the occasion. "Baghdad Bash," it read. "Let's Party."

The Uniqueness of the Gulf War

Reviewing the story of how U.S. F-111 fighter-bombers came to fly over Iraq, helping to start a conflict in January 1991, is a fascinating—and often depressing—enterprise. As recently as March or April of 1990, no one in the U.S. government would have suspected that the United States and an international coalition would be at war with Iraq just months later. U.S. defense and foreign policy had focused on the Soviet threat for forty years, viewing other conflicts as examples of a global U.S.-Soviet competition. But here was Saddam Hussein at the head of a half-million-man army, equipped with some of the world's most advanced military equipment. His scientists were speeding to build chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, which would pose a grave threat to the world's oil supplies. Where did this crisis come from? How did the U.S. military come to be so quickly reoriented from deterring Soviet expansion in Europe to fighting a brutal dictator intent on regional hegemony?

The story of the war, of its prelude and aftermath and, most of all, of its lessons, is the focus of this book. Before we delve into the history of the conflict, though, it is important to understand the war's wider context. To understand the Gulf War one must know where it fits into U.S. foreign policy and why the Rush administration was disposed to react as it did. What business did U.S. troops have intervening in a war between Arab states thousands of miles from U.S. shores? And what is the war's place in history? Ten or fifty years from now, will the Gulf War be viewed (as many instantly proclaimed) as the prototypical conflict of the post-cold war order? Or will it be seen as an interesting but largely discrete event that can do little to inform our understanding of conflict, or to prevent it, in the modern era?

Answering these questions is difficult, in part because the Gulf War was many things to many people. For Saddam Hussein, it was an opportunity to solve his pressing economic problems and become master of 40 percent of the world's oil reserves while staking a bold claim for leadership of the entire Arab world. For George Bush, Hussein's aggression created a clear need to respond to unprovoked aggression and in so doing to begin the redefinition of the U.S. role in the world in the aftermath of the cold war—a necessary exercise for which the administration was ill-prepared. Israel's leaders undoubtedly viewed the war as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see one of their primary nemeses crushed. For the Arab nations of the coalition, a conflict with Iraq was a necessary, if regrettable, response to Hussein's fanaticism and deception; Palestinians and Jordanians, however, welcomed a menacing blow against the rich Arab states, which they believed did not sufficiently share their oil wealth. For Iran it was a chance to condemn and achieve vicarious revenge against its former adversary. For Europe, Japan, and other non-U.S. and non-Arab members of the coalition, the war varied in importance and response from country to country.

Analysis of the Gulf War is further complicated by the fact that it was in many ways a unique conflict. Saddam Hussein's aggression was so brutal, so calculated, so clearly designed for personal and national aggrandizement that it made possible the rapid assemblage of an international consensus against him. The members of the United Nations (not blocked, crucially, by the Soviet Union and China) firmly backed a vigorous response to Iraq's invasion of Kuwait and, following the U.S. lead, granted legitimacy to the coalition's operations with a remarkable series of resolutions. U.S. public opinion was subsequently buoyed by the knowledge that although the war was largely a U.S. effort, it was not entirely so—other nations were also willing to put their soldiers in harm's way to evict Iraq from Kuwait.

The importance of Soviet cooperation cannot be overestimated. If Moscow had continued to support Iraq (as it had during the cold war), the effort to oust Hussein from Kuwait would have become a much more thorny enterprise. In all likelihood, the United Nations Security Council could not have passed any of its resolutions if Moscow had vetoed those proposals. Continued Soviet military supplies to Iraq and Soviet purchases of Iraqi oil would have undermined the economic embargo. It would have been far more difficult to keep an international coalition together on an issue that divided the United States and the Soviet Union: Moscow's few remaining friends and allies would have opposed U.S. actions, Europe may well have become more wary of a conflict, and China might have acquired a new incentive to obstruct U.S. policy. The risks of escalation to U.S.-Soviet conflict would have been present, and as in Vietnam, they might have complicated U.S. military actions. In short, Moscow's assistance in placing pressure on Iraq and its tacit agreement to the use of force played critical roles in the coalition victory.

Equally important was the cooperation of the Arab world, in some cases a quite surprising cooperation. Several Arab states, betrayed by Saddam Hussein or glad to see Iraq defeated, became members of the coalition and in many cases allowed their territories to be used for military operations against Iraq. Others adopted a wait-and-see attitude, forestalling widespread reactions on the "Arab street." Had either group of nations opposed a strong U.S. response to Iraq's aggression, they could have rendered a war far more challenging from a military as well as a political point of view.

Although the war was fought thousands of miles from the United States, it was waged largely from a country—Saudi Arabia—boasting a superb logistical base. Partly with the help of U.S. security assistance, the Saudi government had constructed an amazing complex of huge, modern military installations: King Khalid Military City, the massive air base at Dhahran, the magnificent Gulf port of Jubail, and other such facilities. The full capabilities of this infrastructure, including prestocked supplies, are classified, but it is no secret that the U.S. military enjoyed the advantage of sharing well-maintained, well-stocked bases and ports capable of supporting a large war effort. If those facilities had not existed, or if they had been seized and destroyed by Saddam Hussein's army, the coalition would have faced crippling logistical problems. The buildup of U.S. and coalition military forces would have taken far longer, and the prosecution of the war would have been far more difficult.

Once the coalition began sending thousands of ships, tanks, and planes into Saudi Arabia, Saddam Hussein did little to impede its effort to prepare for war. It is almost unprecedented that one nation would begin a conflict, then sit back and wait, trusting that its potential opponents would not have the political will to respond. Hitler followed a similar strategy for a time—invading Poland and other states, then delaying war with the West in the famous sitzkrieg. But even Hitler, once he recognized that war was inevitable, struck first, sending his armies slashing into France in May 1940. In retrospect Hussein was obviously but inexplicably confident he could absorb the first blow. This provided the coalition with a big edge—but this will certainly not hold true for every adversary the United States will face.

Nor will U.S. forces always operate in terrain that so magnifies their advantages. The flat, featureless desert—with its wide temperature swings between day and night—made even dug-in Iraqi tanks superb targets for U.S. target acquisition and precision weapons systems. Once the coalition gained control of the sky—and there was never much doubt that it would do so quickly— Iraq's forces were immobilized because to move in the open desert was to invite destruction. In other wars, adversaries might be able to hide their forces better in forests, jungles, or cities, and finding and engaging them will be a more difficult enterprise, one less suited to the application of smart weapons.

Finally, the nature of the war also played to the strengths of the United States and its allies. This was a conventional war with battles fought out in the open desert between tanks, planes, and artillery. We knew where the Iraqis were, we knew by and large how many personnel they had, and the front lines were relatively easy to distinguish. This picture contrasts sharply with the conflict in Vietnam, where U.S. and Allied forces fought a hidden, secretive enemy, dispersed within the jungle, seldom emerging in large numbers to fight set-piece battles, relying on hit-and-run raids and the crushing effect of a decade-long war to achieve its victory. President George Bush declared that he would not fight a piecemeal war, as the United States did in Vietnam. Fortunately, he did not have to—Iraq's army was ready and willing to give the coalition a conventional desert war.

Many things that could have gone wrong for the United States and the coalition therefore did not. But any of them could have, and we must not be sanguine about U.S. power and influence because of one unique war. Others can be expected to be very different. It was not so long ago that a collection of ill-equipped, ill-fed, but superbly motivated jungle fighters held the United States at bay for ten years. As Anthony Cordesman and Abraham Wagner concluded after looking at the Arab-Israeli wars: "One must be careful about generalizing too much from the lessons of the Arab-Israeli conflicts.... [T]he lessons of one war are not necessarily the lessons of the next. Further, modern war is simply too complex to reduce it to a short list of simple lessons."2

In a way the Vietnam and Gulf wars form two extremes, examples of the worst and best U.S. leaders can hope for in war. Our concern is to draw lessons from the Gulf War for the more likely cases in between. And although the distinctiveness of the Gulf War obviously circumscribes our ability to draw from it broadly applicable lessons, it does nevertheless offer confirmation of earlier lessons as well as qualifications of still others that had become conventional wisdom. The war in the Middle East is not a perfect subject for study, but no war will be.

The Gulf War and U.S. Policy Changes

The Gulf War, unique as it was, held a broader meaning and carried wider implications than those relating only to military questions or weapons systems: It was both symbol and substance of the sea change in U.S. foreign policy that has taken place since the mid-1980s. It is now almost difficult to believe that Ronald Reagan was elected to the presidency just over a decade ago partly on a promise to confront and roll back the imminent threat of Soviet expansion. The cold war images of Reagan's first term, terrifying enough at the time to rejuvenate worldwide peace movements, now resonate only faintly. NATO's deployment of U.S. cruise and Pershing missiles, the announcement of the Space Defense Initiative (SDI) program, the massive U.S. military buildup to match perceived Soviet advantages—today these events read like ancient history. Almost in a single stroke—the assumption of power in Moscow by Mikhail Gorbachev—U.S.-Soviet hostility began to fade; by the end of his second term, even Ronald Reagan was pronouncing Gorbachev a legitimate advocate of peace. The cold war had begun to thaw.

Describing this new era in dry political and economic terms might not do justice to the dramatic nature of the changes. It is perhaps best to think of the global security environment in a series of images, each representing one aspect of the new context for U.S. national security planning.

January-June 1989. Squat, menacing Soviet tanks sat on railcars, waiting to be removed from Poland and East Germany. In the wake of Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev's dramatic December 1988 United Nations speech, the Soviet armed forces began withdrawing from Eastern Europe. After forty-five years of occupation, over a half-million military personnel would return to Russia and other former Soviet republics. A year later, the Warsaw Pact suffered a death blow because of rebellions or changes of government in all East European states except Albania; later, pact members would officially disband. By the mid-1990s, the equipment and personnel limits of the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty and the confidence-building measures of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) will limit the size and the provocative nature of the Soviet military deployed west of the Ural Mountains.

In short, the threat of premeditated Soviet conventional aggression in Europe, for forty years the bedrock of U.S. and Allied defense planning and the rationale for much of our defense establishment, has disappeared, at least temporarily. Preoccupied with internal political struggles and economic needs, the fractious Commonwealth of Independent States has for the foreseeable future abandoned any notion of territorial expansion or worldwide empire-building. Reforms that Gorbachev unleashed—the radical political and economic change in Eastern Europe and the democratization and fragmentation of the Soviet Union itself—have destroyed almost completely the Commonwealth's formerly monolithic military power.

August 1989. Filipino protesters demonstrated outside U.S. bases, hurling anti-U.S. slogans and demanding the removal of the facilities. During the 1990s, the U.S. military will be hard-pressed to maintain its international network of bases. NATO ally Spain had already set the precedent for such nationalistic base closures in the late 1980s when it asked Washington to leave air bases there. U.S. defense budget cuts will dema...