![]()

1

The Virtue of Insularity

The Lie of the Island

Africa's largest island—fourth in the world after Greenland, New Guinea, and Borneo—Madagascar marks the southwest comer of the vast Indian Ocean triangle, flanking the long coast of Mozambique. The hourglass channel between them narrows to 400 kilometers between Cap St. André and Moçambique Island, billowing wide to 1,000 kilometers at its northern and southern apertures. Tantamount to a small continent both in extent and complexity, Madagascar spans from north to south as far (1,606 kilometers) as the distance between Boston and Atlanta. Its people, the Malagasy, consider their island as a continental expanse rather than as a maritime spot surrounded by ocean. In French, it is familiarly known as "the great island" (la grande île).

A typical insular people, the Malagasy have been able to live their own unique history while communicating fruitfully with nearby shores and distant lands. In the north and west coast towns, Muslim merchants commerced over medieval centuries with the Comoro Islands and the greater Indian Ocean world. Viewed from the exterior, this northern façade of Madagascar appears as a remote frontier of the international system that connected Arabs, Indians, Indonesians, and Chinese, together with Swahili- and Bantu-speaking Africans for more than a millennium.1 In fact, the island's permanent population settled there only quite recently from points in Africa, South Asia, and the Indonesian archipelago. Madagascar's interchange with the Indian Ocean littoral is being belatedly documented, for the island lay far from the core of the great monsoon system.2 It took a more central role in the world only after Europeans had rounded the Cape of Good Hope to defeat that system and link the Indian Ocean with the Eurafrican west. And even that distinction evolved slowly.

Madagascar's insularity is more than a geographical platitude. A hundred million years of biophysical isolation permitted the evolution of a unique natural environment, just as several centuries of political separation allowed the development of a civilization unlike any other. Lying so snugly alongside southeastern Africa, Madagascar nevertheless kept its distance and became something quite different. Apart from curious moments of interchange, the two land masses developed—or rather deviated—in parallel. As the zoologist Alison Jolly describes it, "The world of Madagascar tells us which rules would still hold true if time had once broken its banks and flowed to the present down a different channel."3

During the Upper Cretaceous period, some 50 to 80 million years after the disruption of the ancient unified landmass of Gondwanaland, Madagascar actually broke free from the present area of Tanzania-Kenya. This major fragment of earth carried off a cargo of plants and animals from the contemporaneous stock of East Africa. Some of those species survive to the present time on the island, long after their extinction on the parent continent with its far older population of humans. In most cases, they evolved their own new forms adapted to the hospitable, temperate insular continent. Madagascar thus became a kind of sea-secured museum.

Despite this separate evolution, new species also crossed to the island on winds and tides, at least until the end of the Eocene (40 million years ago). Humans arriving there over the past fifteen centuries have brought their own biological entourage and in their millennium added a new wing to the museum of Madagascar. Records still do not tell us clearly who the original inhabitants were or precisely when they arrived. The second-century Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, the earliest documentary source for the commercial world beyond the Roman Empire, remains silent on the subject. Its maps show Africa rounding off to the west after Cape Guardafui to balance an Asia rounded off at India to the east, leaving no room for Madagascar.4 The island may have been first identified by Arabs, who called it the Isle of the Moon. No doubt people lived on that moon by then, but they weren't consulted on its name. Portuguese captain Diogo Diaz, encountering the big island on August 10, 1500, called it after Saint Lawrence, whose day it was in the Roman Catholic calendar. How or why the good saint's name gave way to "Madagascar" remains uncertain. Marco Polo may have mistaken the island from afar and confused it with "Mogadiscio," actually on the Somali coast to the north.

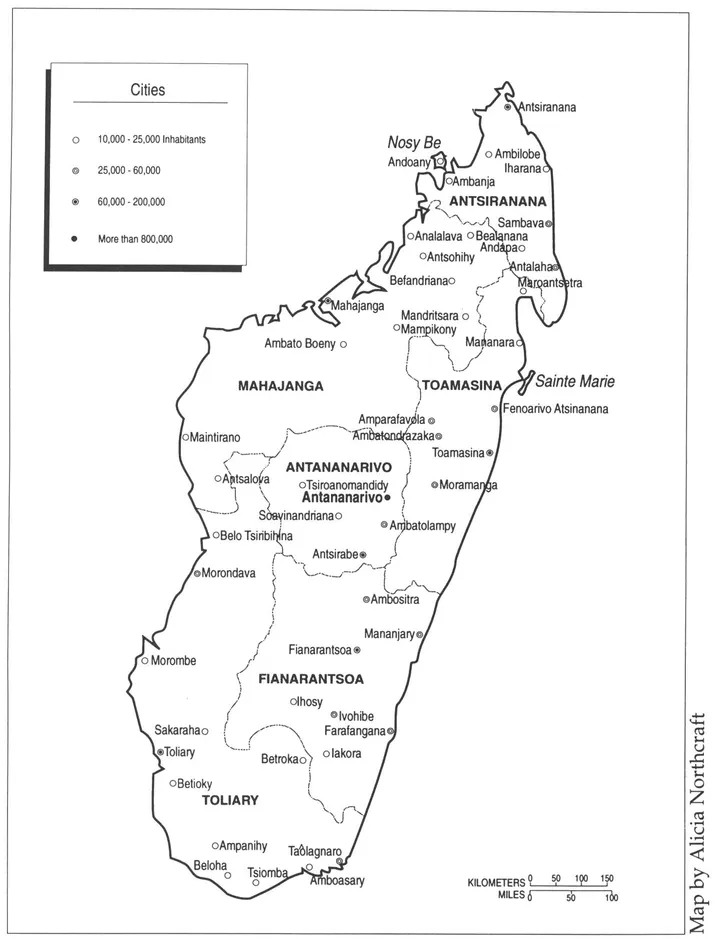

Shaped like a great footprint in the sea, the island slopes toward a toe-point at the north; the vast bay here is Antsiranana harbor (once called Diego Suarez). The contour bulges westward toward Africa below Mahajanga; it tucks in again at the river delta of the Tsiribihina in the midwest and pushes out once more at the mouth of the Mangoky River and the town of Morombe (see Map 1.1). Upstream along these western rivers, the midregions contain grassy savannas with rare remaining deciduous patches begging for moisture. In the southwest, which receives less than 400 millimeters (16 inches) of rain a year, a unique desert of spiny thorn trees is ravaged by periodic drought, and life quivers on the brink of extinction. By contrast, along the even-edged east coast, a steep escarpment deflects the Indian Ocean trade winds into a rain forest that receives from 1,500 to more than 3,500 millimeters of precipitation a year.

West of that escarpment, the land flattens into high plateaus, including the area around Antananarivo (Tananarive in French) at roughly 1,250 to 1,500 meters. Two clusters of volcanic mountains point upward from the plateaus to a peak of 2,880 meters in the northern Tsaratanana range and slightly lower along the island's central vertebrae from the Ankaratra range south of Antananarivo to the Andingitra around Fianarantsoa. Some of the granite up

Map 1.1 Provinces and cities of Madagascar

buddings of central and eastern Madagascar date back more than 3,000 million years, representing "perhaps the oldest rocks on the face of the earth."5 Ravaged by fire, overgrazing, and erosion, the mountains are often entirely devoid of vegetation.

What forest remains after a millennium of such abuse amounts perhaps to 125,000 of the 587,000 square kilometers of total area. There are about 29,000 square kilometers of arable land to support more than 12 million people (barely one acre for each member of a farming family) and an equal amount of prairie for 10 million head of cattle. Rural per capita income has stayed under $100 a year—including the nominal value of subsistence crops—for as long as statistics have reflected Malagasy poverty.

This virtual continent wears a loose wreath of smaller-island satellites about its coastline. Some of the neighboring islets are truly tributary to Madagascar. Others are relatively autonomous. Independent Mauritius, 800 kilometers to the east, once had historical importance as the île de France, headquarters of the short-lived eighteenth-century French empire in the Indian Ocean. Halfway between the two lies hat-shaped Réunion, equally lovely step-sibling of Mauritius in the Mascarenes archipelago.6 Dependent for long periods on sugarcane for their mark in the world economy, both Mauritius and Réunion have grown steadily apart since 1811, the year of Britain's decision to retain the one (Mauritius) and toss the other back to the defeated French.

After generations of economic and demographic vicissitudes, both of these diminutive neighbors have done well for themselves—Mauritius as an indomitable example of pluralist microstate democracy, Réunion as an overseas department of France.7 They have recently grown somewhat closer to their bigger, less-privileged Malagasy neighbor in a western Indian Ocean network favored by European and UN development assistance.

Strewn across the northern mouth of the Mozambique Channel, the four Comoro Islands have bridged that space for warfare, civilized trade, and piracy during a millennium. From Zanzibar or the Tanzanian mainland (Tanganyika), settlers, traders, missionaries, and predators hopped to the Grand Comoro, Moheli, or Anjouan, and finally to southeasternmost Mayotte, where they became intimate with Madagascar. Called Mahore or Maore in the old sea-going literatures, Mayotte has been a French possession since 1841, and its majority has voted three times to remain so in perpetuity. Hence, the island was retained by France after the other three Comoros declared their independence in 1975.8

Several archipelagoes stretching from 300 to 1,500 kilometers north of Antsiranana compose the modern Republic of Seychelles, tiny outpost of nonalignment in a seascape beckoning urgently to Western tourist affluence.9 Together with Mauritius, Réunion (France), and the Comoros, these Seychelles cooperate with Madagascar in regional development undertakings through the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC). Unlike Madagascar and the Comoros, the Seychelles and Mascarenes have blended Asian, African, European, and Malagasy elements into variegated examples of "Creole culture," with a lingua franca based on French, a position of potency for the Roman Catholic Church, and a thoroughly maritime idiom in their institutions.10 By contrast, the Comoros extend Islamic and Swahili culture into the penumbra of southeastern Africa up to the portals of the Malagasy microcontinent.

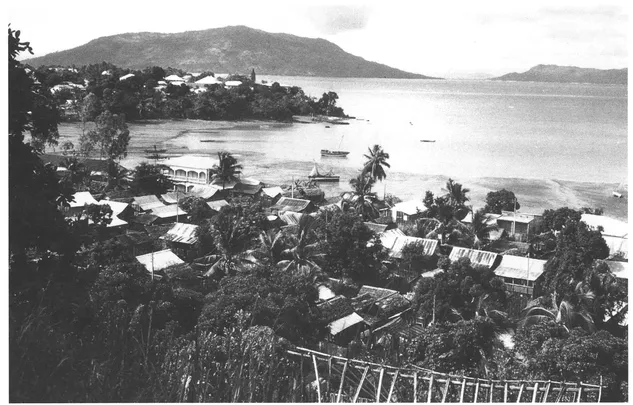

Two or Madagascar's own offshore islands have the size and carrying capacity for historical noteworthiness. Both Nosy Be—westward from the northern tip—and Sainte Marie (also known as Nosy Boraha) off the northeast coast were fortified early in the nineteenth century by France well before French seizure of the great island itself in 1895-1896. In the centuries before this, however, both offshore islands had served other international maritime purposes. Nosy Be (the name means "big island") was an important component of the Sakalava kingdom of western Madagascar and was used for slave raids and pillage of the nearby Comoros—and probably the African mainland as well. In 1840, as the central Malagasy monarchy of the Merina surged outward to the coasts, French admiral de Hell, governor of Réunion, occupied Nosy Be and offered a refuge there to his ally, the besieged Sakalava queen Tsiomeko.

In a somewhat different, more maritime mode, Sainte Marie and the corresponding northeast coast were capitals of Eurasian piracy in the Indian Ocean during the eighteenth century. Here was enacted the stirring story of the pirate republic of Libertalia.11 Later, Sainte Marie was a favorite colony and emporium for French nationals, many of them descendants of the buccaneers and their Malagasy clansfolk. Hence, through the first thirteen years of Malagasy independence, Sainte Mariens were by treaty endowed with dual nationality. But even though the ex-pirate stronghold maintained that privilege, it suffered from severe economic neglect, whereas charming Nosy Be was being cultivated into Madagascar's prime tourist attraction.12

Still another fringe of islets adorns the outskirts of Madagascar, although scarcely with the historical or cultural significance of Nosy Be and Sainte Marie. These are virtually uninhabited, forlorn flecks—the îles éparses—that France persisted in retaining for its own scientific, strategic, and meteorological purposes until 1990. The islets were in fact detached from Madagascar in 1960, just before Malagasy independence, and added to the jurisdiction of France's prefect in Réunion. After three decades of futile protests, the Malagasy have recovered them for whatever purposes they may serve. Several of these islets—Juan de Nova, Bassas da India, and Europa—perch advantageously inside the Mozambique Channel; from them one can view petroleum tankers plowing the seas around Good Hope. The Glorieuses sit just outside the channel to the north. At most, the islets have housed weather research and radio stations, nature sanctuaries, and small detachments of lonely marines or gendarmes who kept the watches of empire along the frontiers of a still strategic sea. But these insular territories give their proprietors important oceanic exploitation rights under the prevailing law of the sea.

Spaciousness and complexity allow Madagascar some independence from its maritime nexus with the outside world. So people came, some of them to stay, and then lost touch with their own origins. An original civilization developed in that space over a period of relative isolation after the first human intrusions. Somehow, it also became a single civilization, cohesive if

Sailing boat harbor of the island of Nosy Be, beyond Hellville (Andoany). Photo courtesy of the Embassy of Madagascar, Washington, D.C.

not uniform in its character. Described in Chapter 4, Malagasy culture is neither Asian nor African despite abundant affinities with both continents. Notwithstanding historically celebrated disparities between coastal and interior peoples, it is one culture. As judged by one of its most assiduous scholars, "Even if undeniable centrifugal forces persist in Madagascar, the society as a whole must be perceived above all in terms of geographic, linguistic, and cultural homogeneity, a phenomenon which places the great island very much on the margin of Black ...