eBook - ePub

Aerial Imagination in Cuba

Stories from Above the Rooftops

- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aerial Imagination in Cuba

Stories from Above the Rooftops

About this book

Aerial Imagination in Cuba is a visual, ethnographic, sensorial, and poetic engagement with how Cubans imagine the sky as a medium that allows things to circulate. What do wi-fi antennas, cactuses, pigeons, lottery, and congas have in common? This book offers a series of illustrated ethno-fictional stories to explore various practices and beliefs that have seemingly nothing in common. But if you look at the sky, there is more than meets the eye. By discussing the natural, religious, and human-made visible and invisible aerial infrastructures—or systems of circulation—through short illustrated vignettes, Aerial Imagination in Cuba offers a highly creative way to explore the aerial space in Santiago de Cuba today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Aerial Imagination in Cuba by Alexandrine Boudreault-Fournier,José Manuel Fernández Lavado in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Wi-Fi

A recent event forced me to shift my ethnographic gaze from the more common horizontal way of seeing to a more vertical form of observation. On the 1st of July 2015, wi-fi antennas were installed in more than 300 public spaces all over Cuba, mainly in parks and plazas. This allowed Cubans to have access to legal wi-fi internet connections for the first time. In Santiago de Cuba, wi-fi antennas were installed in four main areas of the city: three in parks and one in a popular pedestrian boulevard. As part of my research project on media infrastructure in Cuba, I first began to investigate how wi-fi connections alter the ways in which Cubans hang out in parks and public spaces, and second, how they imagine the wi-fi signals travelling from the antennas to their smartphone and laptop devices. Because of the wi-fi antennas (and the phenomena associated with them), my gaze increasingly turned towards the sky. Cubans began to talk to me about wi-fi antennas and how the locations of the antennas in the park influence where they sit and stand to access the best signals. Three wi-fi antennas were fixed on the wall at the bottom of the cathedral in Céspedes Park, the central and busiest park of the city. Many Cubans began to stand in front of the cathedral, not because of a divine call, but because of their desire to catch the best wi-fi signals (Illustration 1.1).

Before embarking on the “aerial imagination” project, which directed my gaze upwards, I did not even know what a wi-fi antenna looked like. I imagined it probably had a similar shape to an analogue TV antenna. I quickly found out that it is nothing like a TV antenna; instead, it looks like a white or grey flat chocolate box. In North America and Europe, wi-fi antennas are everywhere. We rarely notice them, but Cubans do, and they search for them in public spaces all the time.

It was my new gaze, rotated skyward, provoked by the wi-fi antennas, that inspired the idea for this book. This shift of angle in how I looked at the world around me and whether I oriented straight ahead, or up, or down, deeply altered how I began to conceive the ways in which often invisible media, including wi-fi signals, circulate. Thanks to my upward gaze, urban spaces that I never significantly noticed before came to my attention, such as spaces located above the street, on top of buildings, and in the sky. We rarely stop to consider the elevated spaces that make up urban centres, such as rooftops, balconies, and terraces—despite significant social activities associated with them.

Illustration 1.1 Wi-fi antenna in Céspedes Park at night-time.

When I met with José Manuel, the Cuban artist who drew the illustrations for this book, to discuss the “aerial imagination” project for the first time, the idea of developing a story about wi-fi antennas came naturally. The character who will lead us into the mysterious world of Cuban internet and the business of illicit wi-fi connections is named Isaac.

Isaac started a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Oriente in Santiago de Cuba, but he dropped his courses before the end of his first year. He left university, not because he was not talented, but because he was bored by the material covered in class and also because he found his studies disconnected from his life. Isaac is a natural entrepreneur who is always looking for ways to make money. He applies his knowledge of electronics and computer sciences in impressive and creative ways. For instance, he has a neighbourhood word-of-mouth business fixing computers invaded by viruses or in need of upgrades. Isaac is a good example of how Cubans in general cope resourcefully with a precarious economic situation, compounded by the U.S. embargo. Cubans use words like “inventing” (inventar) or “resolving” (resolver), when fixing problems or coming up with alternative products, patterns, or systems for getting things done. In fact, fundamentally speaking, the Cuban Revolution itself, with its values and its models, defiantly challenges the predominant capitalist model. In response to the U.S. and international embargo of the socialist island, the Cuban government promotes and funds local development of pharmaceutical generics and encourages the use of natural medicine, including locally produced herbal remedies and acupuncture, because purchasing medicines from pharmaceutical corporations in other countries is prohibitively expensive. In addition, computer laboratories provide the Cuban population with Linux and other free software. This is in part to achieve technological independence. For example, Nova, an operating system funded by the Cuban state and developed by the University of Information Sciences in Havana, was launched in 2009. These are only a few examples of alternative products, networks, and systems promoted by the Cuban government. Isaac echoes this general tendency of responding to scarcity in ingenuous ways. One day, Isaac told me that “inventing” is a way of life in Cuba, as citizens have no choice but to cope with scarcity—food, hygiene products, transportation, communication, money, etc.—in creative ways as a matter of survival.1

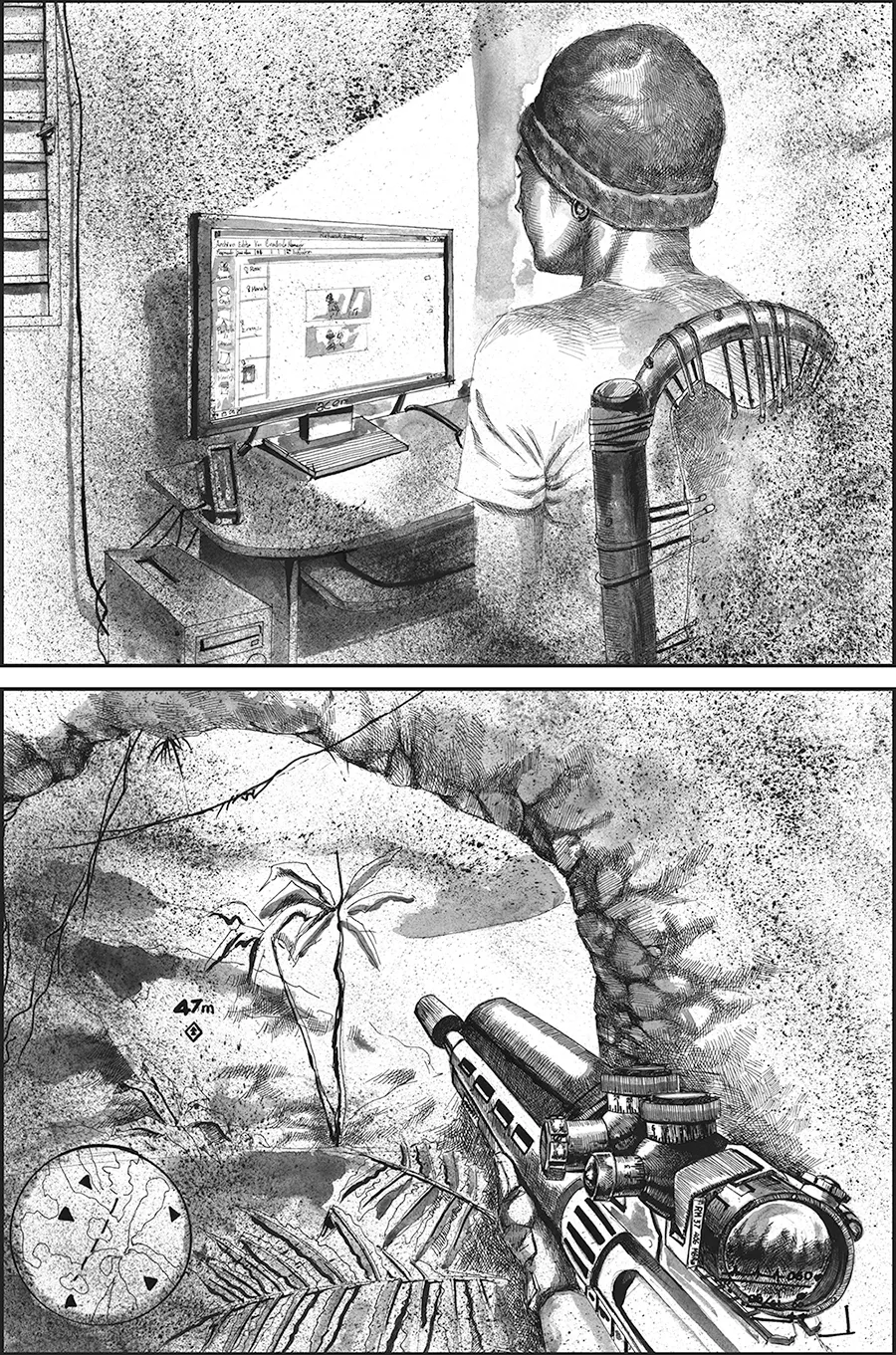

Isaac’s mother is a doctor. She spent two years in Brazil on a “medical mission,” a programme whereby the Cuban government sends medical personnel to other countries. Thanks to this, she was able to purchase and import from Brazil a desktop computer for the family. Isaac quickly monopolised the computer to play video games (a pirated version of Call of Duty being his favourite, Illustration 1.2). Despite owning a computer, it was impossible for Isaac to access the internet, a service that is still not available in his neighbourhood. Yet, his desire to play online with his friends who also owned computers (not common in Santiago) drove him to develop an alternative system to connect various PCs located in different houses. In a country where access to the internet is extremely limited, connectivity is something Cubans do not take for granted.

Only a minority of the Cuban population has regular internet access. Also, access rates are low outside the capital, Havana, particularly in rural areas and in the eastern provinces of the island. Until recently, internet has been carefully controlled, providing only certain people (for instance, doctors, students, and professionals) the right to have an email account within a national system (intranet), and, less frequently, an international account. Very few have internet at home, and their connections, until very recently, relied exclusively on a dial-up system. Suppliers of illegal internet connections risked long-term jail sentences if caught. Until the beginning of the 2010s, only foreigners could use the internet in hotels and ETECSA2 offices. But in May 2013, the Cuban government inaugurated 118 internet stations, placing them inside state-owned ETECSA offices located all over the island (ETECSA is the only internet provider in Cuba). For the equivalent of USD 4.50 per hour, the state provided would-be web surfers with ID cards, registered by their local ETECSA office, and, finally, Cubans could legally browse the internet on one of the ETECSA’s PCs. However, given that typical Cuban state salaries range between USD 15 and 30 per month, a price of USD 4.50 per hour was accessible only to Cubans with non-state sources of income (such as families receiving remittances from abroad, those working in the tourist industry earning tips in hard-currency, or folks with “grey market” or “black market” businesses offering everything from tours to Bed and Breakfasts to private restaurants to salsa lessons to non-licenced renovation to imported goods) operating in informal economies. But as mentioned before, it was not until 2015 that legal wi-fi connections in public spaces became available to the Cuban population. As time passed, more antennas were installed in varied public spaces and internet service became cheaper. During the summer of 2018, Cubans could purchase a wi-fi connection card for USD 1.50, which gave them a one-hour connection. There are also illicit vendors who offer one-hour wi-fi connection for a discount: only USD 1.00. In Cuba, a 50-cent difference in price is meaningful. We will learn more about these illicit wi-fi venders in this story.

Illustration 1.2 Isaac plays video games “online.”

The prices for internet services have dropped each year since the Cuban government first began to offer legal connectivity to the general population. For instance, in 2017, it was announced that ETECSA would begin to offer home internet connectivity following a successful pilot project called Nauta Hogar, which was first launched in the historic district of Havana and later expanded across the island. Nauta Hogar offers 30 hours of wi-fi internet connection at different speeds (kbps) for prices ranging from USD 15 to 70 per month. The service is available only to clients who already own a home landline (see Chapter 5). In December 2018, ETECSA began to sell the 3G service—internet on cell phones—which can be purchased starting at USD 7 for up to 300 MB of download capacity. But, again, given the official average salary for even a skilled professional in the public sector, much less a lower-paid manual worker, internet access remains out of reach for a large segment of the population.

Whilst the internet has become increasingly available in Cuba, it has been through a pay system that accentuates disparities between those who can afford the internet and those who cannot. Freedom House, an American watchdog organisation dedicated to freedom and democracy around the globe, estimates that 5%–26% of the Cuban population had access to the internet in 2014.3 According to the same organisation, Cuban internet penetration rates increased to 38.8% in 2018.4 Despite this impressive increase, internet connections remain unreliable, patchy, slow, and expensive. The media scholar Cristina Venegas argues that three principal motives can explain why the internet was not (and still is not) accessible to the majority of the Cuban population—namely, political, financial, and infrastructural (Venegas 2010, 58; also see Recio Silva 2014). Venegas argues that “Whether or not the Internet … may be a threat to Cuba’s own democratic aspirations, it is surely so perceived by the government” (2010:185). Still, the recent increases in connectivity options mean that, overall, Cubans have more opportunities to access email, keeping in touch with family or friends abroad via apps like IMO or Facebook Messenger, and digital data including music, films, and digitally available newspapers and websites.

As Cubans get in touch with their families and friends living abroad through the internet, parks with wi-fi connections are transformed into hotspots where people can communicate with those outside the island. Most Cubans go online knowing that they have a limited time to navigate. This creates a sense of hurry and stress as the seconds (and money) fly away. Such a phenomenology of the internet is something few in the global north can identify with—at least today.

Alternative networks have emerged to counter the inefficiency and unreliability of the official state-run media infrastructures in Cuba. One of them is the paquete, a weekly digital media package distributed through memory sticks and other portable devices, that allows Cubans to access music files and videos, films, telenovelas, talk-shows, and other audio-visual products such as documentaries. The paquete also includes lists of ads for new and used items (from computers to memory sticks to dogs) for sale by individuals, as well as services being offered, similar to the site Craigslist. The paquete providers use various illicit strategies, including downloading data from internet con...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Wi-Fi

- 2 Cactus

- 3 Pigeon

- 4 Lottery

- 5 Conga

- Conclusion

- Index