- 349 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book focuses on the political-economic dimensions of the food crisis, with case studies from the four regions—Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East—of the Third World. It examines various international factors that influence agricultural development in the Third World.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agrarian Reform in Reverse by Birol A. Yesilada in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Agrarian reform programs in the 1960s and then the Green Revolution were to have accelerated the modernization process so that hunger would be substantially eliminated throughout the world. Instead, the number of the malnourished in the Third World continues to grow. The cause of this tragedy is much more than the inexorable increase in population growth. At least equally important are patterns of land and food distribution and the underlying determinants of these patterns, namely, the interrelated factors of political power and economic structures.

Agrarian reform programs were much easier to formulate than to implement. In few countries did the configuration of political power allow meaningful redistribution of large inefficient holdings; rather, the usual result was their transformation to modern commercial operations along with the distribution through colonization of unused and less desirable lands. It was these commercial farmers, not the far more numerous subsistence peasants, who were most able to take advantage of the technological package of the Green Revolution. And, many of the peasants who were able to take advantage of the new techniques had to revert to traditional practices when the oil price shocks of 1973 and 1979 escalated the prices of fertilizers and fuels.

As commercial agriculture has spread throughout the Third World, it also has become increasingly integrated into international capitalist economy. A primary stimulus for many commercial growers has been the profit to be made producing for foreign markets. Their production has been facilitated by public policies of governments eager to expand their foreign exchange earnings. This motivation has been reinforced greatly by the debt crisis of the 1980s. The abundant supply of capital created by the petroleum profits of the 1970s needed to be recycled by the international banking community. It found ready customers in Third World governments that wanted loans to cover costs of petroleum imports and development projects rather than cut back on their ambitious plans. These escalating foreign debts collided with the harsh world recession of the early 1980s, creating economic crisis throughout the Third World. Just to service their debts, much less repay them, now countries must further direct their economies toward available export markets, which for the Third World often means agricultural commodities.

If agrarian reform means progressive changes intended to create a more egalitarian rural society, then these recent dynamics have produced agrarian reform in reverse. Smallholders have been squeezed out of land markets and sometimes coerced off of their land. When combined with population growth, a rapidly increasing rural proletariat has been created, often unemployed or underemployed. Numerous others migrate to urban areas, often just transferring the problem. Land that previously had been planted in food staples now produces cotton, pineapples, sugar cane, soybeans, groundnuts, etc., or grazes cattle for export, usually to more developed countries. As domestic food production stagnates, it has fallen behind population growth rates in many countries.

Estimates of world hunger vary depending upon the method used but all agree that the number is huge. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) claims that 436 million people suffer from undernourishment (FAO, 1985: 5) while the World Bank (1986: 3) put the number at 730 million, as shown in Table 1.1. The proportion of people with deficient diets in 1980 was virtually unchanged from 1970 and, therefore, the absolute number has increased. The World Bank (1986: 18) has estimated that the ten percent diet deficient category increased by ten percent and the twenty percent diet deficient category increased by fourteen percent. It has been claimed that in the 1980s, starvation and hunger-related diseases still cause 35,000 deaths per day and 13–18 million deaths per year (Hunger Project, 1985: 7).

The causes of this continuing tragedy have many dimensions. This volume concentrates on the political-economic. The contributors are organized into two sets. Part 1 includes case studies from each of the four regions of the Third World: Africa (Kenya), Asia (Philippines), Latin America (Brazil, Ecuador, Honduras, and Peru), and the Middle East (Turkey). There are certainly situations and

Table 1.1 Energy Deficient Diets in Developing Countries, 1980 (millions of individuals)

| Country Group(n) | 10% deficiencya | 20% deficiencyb | ||

| pulation | % Of pop. | population | % Of pop. | |

| | ||||

| All LDCs (87) | 730 | 34 | 340 | 16 |

| Low-income (30) | 590 | 51 | 270 | 23 |

| Middle-income (57) | 140 | 14 | 70 | 7 |

| Sub-Sahara Africa (37) | 150 | 44 | 90 | 25 |

| E. Asia and Pacific (8) | 40 | 14 | 20 | 7 |

| South Asia (7) | 470 | 50 | 200 | 21 |

| Middle East and North Africa (11) | 20 | 10 | 10 | 4 |

| Latin America and Caribbean (24) | 50 | 13 | 20 | 6 |

a 10 percent deficiency means that the person is receiving 90 percent or less of the FAO/WHO requirement and does not have enough colonies for an active working life.

b 20 percent deficiency means the person is receiving 80 percent or less of the FAO/WHO requirement and does not get enough calories to prevent stunted growth and serious health risks.

Source: World Bank (1986:17).

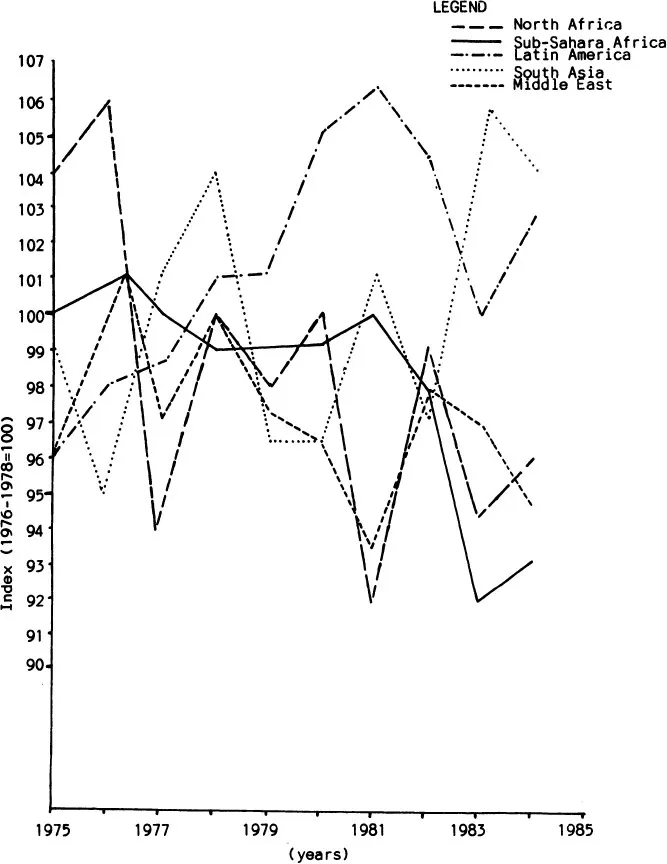

determinants unique to each region and country, as suggestively portrayed by Figure 1.1, for example, which presents the varying regional patterns of per capita food production in recent years. Nonetheless, each of these examinations of the relationship between agricultural policy and food security reinforce this volume’s theme of “agrarian reform in reverse.” The analysis shifts to the international level in Part 2. In this section the contributors examine various international factors that influence agricultural development in the Third World. These factors are: dependency in international trade and monetary relations, the IMF conditionality in Latin America, the Cereals Imports Facility of the IMF, the Rome Food Agencies, and the U.S. foreign agricultural policy toward the Third World.

Part 1: Case Studies of Induced Change in Agriculture Policy

The Latin American case studies are of very different countries yet they portray similar forces at work with similar consequences. Honduras is one of the poorest countries in the region and one of the most rural. Nonetheless, there has been substantial change in the Honduran countryside in recent decades, as the Brockett chapter demonstrates. The spread of modern commercial agriculture has advantaged part of the rural population but, when combined with rapid population growth, has diminished economic security for many others. Responding especially to the stimulus of export markets, commercial farmers have expanded their holdings and production. Conversely, subsistence farmers have lost access to land and the rural population to food. Across recent decades, per capita domestic food production has declined as has per capita beef supply; meanwhile, the relative share of land devoted to export crops as compared to food crops has increased substantially, as have beef exports. The second part of this chapter examines the political context of these socio-economic changes. Domestic and international political actors have promoted agricultural modernization and export expansion. At the same time, the state has had to contend with a peasantry that mobilized in response to the deleterious effect of these agrarian changes on their lives. The most important of the state responses has been an intermittent program of land reform, one that has been unable to keep pace with the growing numbers of landless and landpoor peasants.

Figure 1.1 Food Production Per Capita in Developing Countries

Source: USDA. World Indices of Agricultural and Food Production, 1975–1984.

Brazil has a gross national product about eight times larger than that of Honduras, a population about 31 times larger, and has almost twice the percentage of its people living in urban areas. In their agricultural sectors, though, similar forces have been at work in recent decades. Drury’s chapter documents the successful expansion of export agriculture in Brazil. At the same time, however, per capita production of major food crops stagnated or declined across the decade ending in the early 1980s. The two trends were related: land planted in the export crops rose dramatically while only minimally for the food crops. As consequences, caloric intake declined, inequality of land access increased, and rural unemployment rose. In explaining these dynamics, Drury gives particular attention to the debt crisis and the consequent need to increase foreign exchange earnings through agricultural export expansion. A further result was to end already feeble attempts at land reform. Agrarian reform in reverse in Brazil also has led to increasing rural tensions; conflicts over land provoked an average of twenty deaths a month in 1986 (Lanfur, 1987: 11). “Export agriculture,” as Drury points out, “has defeated food and reform.”

The McClintock chapter doubly enlarges the comparative focus of the case studies of Part 1. Her two countries of Ecuador and Peru fall between Brazil and Honduras in per capita GNP; furthermore, her case material allows a comparison of two major competing approaches to agrarian policy. On the one hand, a progressive military regime in Peru undertook a major land redistribution during 1968–1975, organizing much of the reform sector into cooperatives. In contrast, the promotion of capitalist agriculture with little attention to land reform has characterized agrarian policy in Ecuador throughout the period examined and in Peru under an elected civilian government during 1980–1985. Through her in depth analysis of public policy and its consequences, McClintock finds that although the Peruvian reform often has been faulted, the performance of its agricultural sector consistently equals or surpasses its Ecuadorian counterpart on the indicators studied. One notable difference in the two approaches concerns export agriculture. Public policy in Peru during the reform period attempted to redirect the traditional export commodities to the domestic market; in Ecuador, however, the contribution of export crops to the value of agricultural production more than tripled from 1970 to 1985 while production of food staples stagnated. At the more fundamental level of food security, though, what is most striking is the similarity in results: per capita food production has declined in both countries, necessitating increases in food imports that inadequately meet growing needs. The causes are familiar, ranging from the power of landed and other elites to resist or undermine reforms, government policies that favor larger landowners, world recession, foreign debt crisis, and pressures from the IMF and the U.S.---many of which McClintock summarizes as these countries’ more thorough “integra[tion] into the world capitalist economy.”

The next chapters expand the points of comparison, not only by bringing in the other regions of the Third World, but also by providing variations in population size and level of development. With populations around fifty million in the early 1980s, both the Philippines and Turkey have much larger populations than the other countries, with the exception of Brazil. In per capita GNP, Turkey falls between Brazil and Peru while the Philippines ranks between Peru and Honduras. Kenya has a population about the same size as Peru but with a per capita GNP almost one-third less, making it the poorest country...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- 1 Introduction

- PART 1 CASE STUDIES OF INDUCED CHANGE IN AGRICULTURE POLICY

- PART 2 INTERNATIONAL FACTORS AND AGRICULTURE IN THE THIRD WORLD

- Contributors