- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Rural Communities

About this book

This book is dedicated to the people of rural America whose struggle to make community meaningful provides important lessons. It includes the contributors' prescription for the 1990s that calls for a renewal of action, development, and leadership on the part of local citizens and civic leaders.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Rural Communities by A.E. Luloff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

A.E. Luloff and Louis E. Swanson

Overview

This text is comprised of a series of original essays by people working in both a basic and applied policy relevant research setting. Unlike other contemporary efforts on the American community, the focus of this text is the rural sector of the United States.

Rural America contains almost one of every four Americans on a land base which occupies about 97% of the nation, and which accounts for more than 30,000 general purpose agencies. The absence of a focused effort on the conditions and opportunities confronting this segment of America has impeded the development of a national rural development policy. Instead, there has been a fixation on the part of researchers and policy makers on U.S. Census urbanized areas, a total land base which comprises only slightly more than 2% of the nation (Beale, 1988, personal communication). In this text, a renewed focus on the geographically larger and structurally more diverse rural component of American society is provided. It is the collective belief of the authors of this text that such an effort is necessary, particularly if solutions for many of the problems associated with urban life (clean water, open space, solid and hazardous waste disposal, among others) are to be found.

Some, however, might question such an effort, particularly those who embrace the "plug-in, plug-out society" of Toffler (1970) and the "mass society" notions of Olson (1963) popularized in the press of the last two decades. From either of these latter perspectives, concern is properly placed on the bigger picture—and the prevailing societal tendency for a concentration of social and economic activities in large urban and/or metropolitan centers.

Such locales have dominated the attention of politicians for more than 50 years. The overwhelming majority of Congress is of urban origin (reflecting the preponderance of the country's population) and their general absence of concern with respect to rural development issues is not terribly surprising.

Events of the last several decades helped to further erode interest in rural concerns. The completion of the interstate highway system and improvements in telecommunication networks have enhanced the dominance of the urban agenda. Even the much heralded rural revitalization of the early 1970s, during which nonmetropolitan areas experienced a faster rate of growth than their metropolitan counterparts, was a major signal of the kinds of new linkages, and likely dominance, of the core to the peripheral areas of the nation.

Despite the claims of many that this period of nonmetropolitan expansion heralded a new era, it now appears to have been only a temporary aberration to the traditional pattern of faster growth in metro areas. At the same time, recent evidence of a widening gap between rural and urban incomes has been generated, especially during the period of faster nonmetropolitan growth.

Such differentials created opportunities for large transformations to the profiles of both the socioeconomic class and work force structures of nonurban society. Further, with continued population growth and U.S. Census definitional changes, many of these nonmetro areas have become small metro centers, contributing to the idea of a growing suburbanization of America. The metropolitan expansion/spillover framework of many urban ecologiste may account for some of this diminution but not all.

In addition, the popularization of the "information age" psyche has created numerous opportunities for plugging-in-and-out. Examples of the latter include cottage industries, spin-off industries in the last stage of product life cycle, and the process of diffusion of industrial innovation from metro centers to nonmetro areas. In each of these situations, management decisions are made quite differently than before, and have ramifications far beyond the confines of the local business enterprise.

There is increased justification for a text like American Rural Communities. It is time for an examination of the plight of modern existence in rural America. Unlike many other efforts, no attempt is made here to perpetuate a myth of rural life. The rise of interest in the nonurban component of society, first signalled in the reports of various polling firms during the early 1970s, and authenticated by widespread residential, commercial, recreational, and industrial growth and development, particularly in areas well within commuting distances of major metropolitan centers, buoyed an emergence of a national buccolomania.

Glorified perceptions of rustic life amid weather beaten stores, factories, and home fronts belied the general ignorance of the situations characterizing rural America. Popular magazines and newspapers (Country Journal, Yankee Magazine, Grit) romanticized life in the nation's rural areas and contributed to the perpetuation and growth of many of the myths associated with a rural existence.

Despite the efforts of modern authors, whatever their motives, and the many conveniences of contemporary existence, life in rural America was never easy. From its inception to as recently as 1920, the nation was dominated by its rural sector. No where else was nature as bountiful an ally or as powerful an opponent. Rural life revolved around extractive activities, including farming, fishing, forestry, and mining. Further, such occupations have generally been viewed as being quite hazardous. Involvement in these pursuits has been a central component of most definitions of rural life.

At the same time, a growing mercantile and service trade emerged to cater to the needs of America's rural citizens. Only sixty or seventy years ago, many of these small businesses reflected the personalities of individuals steeped in the democratic principles so eloquently identified by de Tocqueville (1945). Many businesses in modern rural communities now mirror principles of the dominant urban society. Such a transition does not occur with impunity. An absence of the wealth of local involvement characteristic of earlier periods has had repercussions throughout the local community. There are simply fewer of the small scale yet skilled entrepreneurs which once thrived in rural areas.

With this loss has come a precipitous decline in the rural middle class (roughly 20% today as compared to estimates of as much as 70% in 1930). The modern rural middle class tends to be involved in the management of private and public institutions. Such institutions are vertically linked to power structures located in the dominant urban sector. This newly defined class cannot be viewed as entrepreneurial since they are not owner/ operators, but rather employees. Thus, while many of the same management skills still exist in rural areas, they are often channeled in different directions. And it is not at all clear that the agencies and businesses for which these people work are interested in allowing or encouraging their employees to become involved in local community issue resolution.

Local economies have, in turn, evolved into a dependency upon manufacturing, especially latter stage product life cycle facilities, old nondurable production plants, and modern assembly plants (both durable and nondurable). This movement parallels the shift to wage labor which has characterized recent rural economies, and contributes to a single sector dominance of the local society.

What the short and/or long term implications of such a shift are for rural America is not at all clear. Despite its importance as a source for the nation's water, land, and other natural resources, there has been no success at developing a national rural development agenda. This absence has impeded policy formation. American Rural Communities attempts to address this shortcoming.

Organization

This book contains a collection of twelve essays from fifteen individuals who have attempted to accomplish two things in each of their chapters: (1) to provide a state of the art review of the identified area of their expertise and/or interest; and (2) to then offer a prescription for the 1990s. This prescription calls for a renewal of action, development, and leadership on the part of local citizens and civic leaders. It is argued that without a partnership between state and local governments and rural communities, the future of this vital sector of the national economy will be bleak.

Luloff in "Small Town Demographics" provides a review of national population changes by size of place and metropolitan/nonmetropolitan status for the period 1960-1980. The importance of the small town to the nation is underscored, and the relationship between natural resources and community survival is outlined.

Swanson in "Rethinking Assumptions About Farm and Community critiques the popular assumption which links the financial fortunes of the farm sector to the economic and social well-being of rural community. His brief historic review of several studies which have used this relationship as a guide provides important insights into some of the reasons behind the lack of a rational rural development policy.

Humphrey's "Timber Dependent Communities" focuses attention on the relatively understudied forest component of rural society. Despite being America's major renewable resource, which has experienced large increases in net annual timber growth as a result of technology and science, the future of timber dependent communities remains unclear. Two scenarios with quite distinct consequences for this small but important sector of rural America are presented.

Krannich and Greider's chapter provides a new conceptual framework for understanding "Rapid Growth Effects on Rural Community Relations." They argue that the almost overnight thrust of small communities caught in a boom cycle into the complexities of advanced industrial societies may create innumerable opportunities for enhanced interpersonal interactions. According to the authors, rapid population growth can contribute to a revival of communal association, thereby confirming the resiliency of rural residents while raising serious questions about the dominant perspective on this process in the literature.

"The Character and Prospects of Rural Community Health and Medical Care" contains in one location, for the first time, a thorough review of the state of health care in the rural sector of our nation. Clarke and Miller identify many of the key differences between rural and urban areas' access and utilization of health care facilities, manpower, health care service delivery, and financing. As a result of their effort, attention can be focused on the holes in the extant knowledge base which have remained unfilled during the last decade.

Ilvento's work on "Education and Community" changes the issue from one of the impacts of schools on individuals and families to one where the focus is its impacts on community. Much of the current source of tensions in the educational system centers on the debate between those making the decisions and those who pay for the delivery of the service. From a community development perspective, we often laud local decision making; according to Ilvento, this process may have led to the present inequalities characteristic of our nation's rural school systems.

Ploch's "Religion and Community addresses the relative absence of recent research on the role religion has played in the life space of today's small rural communities. The author describes the strong linkages between church membership and the attendance and local social standing in the colonial period, and elaborates on the legacy and role of such connections in modern community life. An attempt is made to demonstrate the dynamics of religion in rural communities, with particular attention on the increased participation of those historically excluded from the mainline churches.

In "Crime and Community Wilkinson presents an argument for the application of interactional theory in research on crime and its sources. Conventional research has mistakenly been preoccupied with questions concerning the functions and dysfunctions of social control. The author provides an alternative perspective which suggests that both crime and community have the same roots in social interaction. In this approach, a more holistic conception of community is utilized, and crime is defined as a disruption in social interaction as opposed to social order.

Voth and Brewster's chapter on "Community Development" traces the meaning and origin of rural community development efforts by making use of four complementary perspectives. The roles of voluntarism and self-help, particularly in small communities, are identified as key aspects of early national development. A call is made for a more thorough and scientific evaluation of the efficacy of existing programs prior to beginning new efforts in this arena.

"Community Leadership" by Israel and Beaulieu presents a cogent argument for answering a series of questions about the capacity of local leaders to respond to the increasingly fragmented and specialized problems confronting rural communities. Modem municipalities have begun to exhibit a greater reliance on government agencies for guidance, support, and operating funds. The authors suggest that in an era of tightened budgets at all levels of government, there will be a need of new mechanisms for training local leaders and a concerted national effort to help overcome structural constraints to local community action.

Sokolow in "Leadership and Implementation in Rural Economic Development" argues that most economic development successes at the local level are the result of external, particularly state and federal, assistance. Such reliance has contributed to a diminution of local capacity building. The author suggests that changes in federal policy coupled with increased realization of local potentials may lead to a resurgence of local initiative in the economic development process.

In "Community and Social Change: How Do Small Communities Act?" Luloff suggests that an adherence to the traditional perspective of monitoring institutions and boundaries has diverted attention away from a recognition of the important role human volition plays in local activity. Recent literature supports the premise that small and rural communities can and do act. The author proposes that by moving beyond the structural context to an examination of the processes through which actions are undertaken, more insight into the capabilities and limitations of local communities in effectively responding to issues can be realized.

The final chapter summarizes the themes of the book. It is argued that important structural factors often impede rural community development, but, even so, the key to community action is the ability of people in a given local society to organize their scarce resources and to act collectively and democratically in their mutual interest. While community is not easily accomplished, neither has it been eclipsed by the industrialization process.

As the burden of community economic and social development shifts public policy towards state and local governments, we will need to understand how scarce resources are organized and what structural barriers act to inhibit community enhancement. It is an assumption of these authors that the study of community is not only exciting and rewarding, it is also of use to people attempting to make sense of and to act upon the local events of their daily lives.

2

Small Town Demographics: Current Patterns of Community Change

A.E. Luloff

In this chapter we examine patterns of change in American communities. Particular attention is placed on the metamorphosis of many small and rural towns. A common thread among the majority of these places is the central role played by natural resources and the resultant extractive way of life. Linkages are drawn between these resources and the concomitant lifestyles in framing the portrait of small town change.

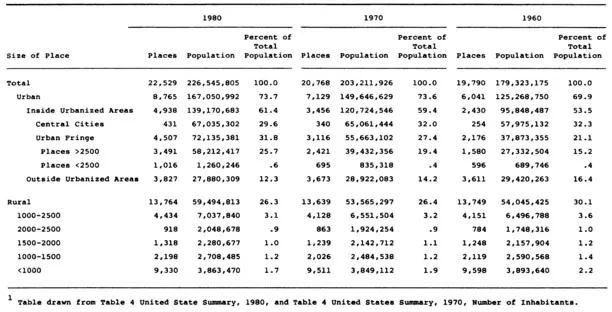

Life in large cities is a relatively recent phenomena. The United States did not become predominantly urban until 1920. More than one-half of the population (54,158,000 as opposed to 51,553,000), was classified as living in an urban residence. With such a late shift to the vastly predominant form of urban residential life characteristic of the nation today, it seems a bit surprising that so little recent attention has focused on the role and place of the small community. The work of Johansen and Fuguitt, 1984, is one notable exception. In order to provide some insight into current patterns of change among various size places, the distributions for the period 1960-1980 (see Table 1) are presented below.

The number of places has increased by about 2,700 since 1960, with the bulk of the change occurring between 1970 and 1980. Almost all of these absolute increases affected places in urban areas. As the upper panel of Table 1 indicates, regardless of whether inside or outside of urbanized areas, there has been a monotonie increase in the number of places in each size category. The fastest growth occurred in the urban fringe, especially among places >2,500, and in central cities (70% increase between 1960 and 1980). In 1980, almost three of every four individuals resided in an urban designated area and more than six of every ten resided inside an urbanized area. During the same period the small urban communities (<2,500) and those outside the urbanized area accounted for a decreasing

Table 1:Population by Size of Place, 1960-X9801

share of the total urban population. Despite this decline, more than 4,800 small communities remained "home" for almost 29,000,000 Americans in urban areas in 1980.

An examination of the lower panel of Table 1, which disaggregate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Small Town Demographics: Current Patterns of Community Change

- 3 Rethinking Assumptions About Farm and Community

- 4 Timber-Dependent Communities

- 5 Rapid Growth Effects on Rural Community Relations

- 6 The Character and Prospects of Rural Community Health and Medical Care

- 7 Education and Community

- 8 Religion and Community

- 9 Crime and Community

- 10 Community Development

- 11 Community Leadership

- 12 Leadership and Implementation in Rural Economic Development

- 13 Community and Social Change: How Do Small Communities Act?

- 14 Barriers and Opportunities for Community Development: A Summary

- Bibliography

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Index