eBook - ePub

Comparing New Democracies

Transition And Consolidation In Mediterranean Europe And The Southern Cone

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Comparing New Democracies

Transition And Consolidation In Mediterranean Europe And The Southern Cone

About this book

The transition to democracy has been a significant trend in Mediterranean Europe and Latin America during the last ten years. This book presents comparative analyses that offer a theoretical synthesis of the dynamics of recent democratization processes on both sides of the Atlantic. The contributors argue that transition is a response to fundamenta

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Comparing New Democracies by Enrique A. Baloyra in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part One

Theoretical and Comparative Perspectives

1

Democratic Transition in Comparative Perspective

Enrique A. Baloyra

Anyone who has studied democratic transition, as have the contributors to this book, knows that the similarities among the cases, at least those similarities observable at the national level of analysis, prove to be poor predictors of a democratic outcome.1 Preliminary comparative analyses of transition have suffered from a failure to look at this process from the "inside" to determine what separates success from failure (a contrast between the chapters on Brazil and Chile will be very instructive in this regard). Nevertheless, there is a need for some kind of framework against which to evaluate the maze of details and contradictory evidence concerning a particular process of transition. The chronological sequence of events must be broken down into some more or less discrete, meaningful stages; and the substantive and procedural aspects of the process of political transition, especially the issues that precipitate its "endgame" phase, need to be described. Any discussion of democratization in Latin America must refer to the basic arenas where politics takes place, particularly in a situation in which one system of authority is unraveling while a substitute is not yet in place. Definitional rigor should prevail at the nominal and operational levels so that the ambiguities and contradictions found at the empirical level may be interpreted correctly and may not be confused with descriptive gaps resulting from chaotic semanticism. Basically, this chapter is an attempt to clarify these concepts. It is a comparative exercise (with some reference to cases not included in this volume) as well as a guide to the chapters that follow.

The Dimensions of Political Transition

A succinct review of the more prominent characteristics of these transitions would suggest that they have been more frequent in the more advanced forms of authoritarian domination; that they have responded primarily to endogenous impulses; that they have been managed by military coalitions seeking to liberalize and reequilibrate the current regime or to extricate themselves gradually through a strategy of free and competitive elections; that they have required the neutralization of extremist obstructionism in endgame episodes; and that the failure to address the agenda of transition in full has resulted in weak consolidations and incomplete democratizations. The review of the cases will show that these "partial victories" did not come easily, as they required extraordinary exertions of political will.

The point of departure in these processes has been a capitalist state with a regime d'exception (regime of exception) maintained by a dictatorial government seeking to contain the society and to control an exclusionary political community.2 The end result is the disappearance of the authoritarian regime (defined here as the arbitrary rule imposed by a dictatorial government). The disappearance of this regime does imply the emergence of a new regime in which the government does not abuse its powers because it is constrained by autonomous intermediary institutions (I offer this as a concise, generic definition of democratic regimes). These are the most basic elements that these processes have in common.

By a process of democratic transition I mean, (1) a process of political change (2) initiated by the deterioration of an authoritarian regime (3) involving intense political conflict (4) among actors competing (5) to implement policies grounded on different, even mutually exclusive, conceptions of the government, the regime, and the state; (6) this conflict is resolved by the breakdown of that regime leading to (7) the installation of a government committed to the inauguration of a democratic regime and/or (8) the installation of a popularly elected government committed to the inauguration of a democratic regime.

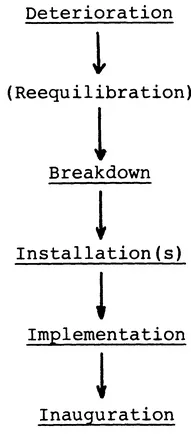

The temporal dimension implicit in this operational definition is presented in Figure 1.1. Whatever sequence is implied in the figure does not presuppose an orderly, irreversible progression through neatly differentiated stages. What is depicted in the figure is a series of major, albeit distinct in some instances, recurrent events that takes place during the transition. The events themselves are conceptualized in terms of the following definitions.

Deterioration is the loss by an incumbent government of its ability to cope with the policy agenda, particularly the two key concerns of political economy—security and prosperity—and other salient issues of high symbolic appeal to the public. Deterioration is the situation in which governments find themselves when they are unable to conjugate minimally acceptable levels of efficacy, effectiveness, and legitimacy.3 Governments and regimes deteriorate, but this is not conducive to a process of transition unless there is a breakdown—that is, a collapse of the incumbent government followed by a marked discontinuity in the nature of the regime. Breakdown can occur without deterioration as a result of the sudden death or assassination of the head of state, a scandal of major proportion, or other events that paralyze the government and bring about its downfall. The evidence suggests that in most cases deterioration is not followed immediately by breakdown because most governments institute measures designed to reequilibrate their regimes and keep them in power. Many authors refer to the dynamics surrounding the deterioration of authoritarian regimes as an authoritarian crisis (crisis is a perfectly viable although much-abused term).

FIGURE 1.1 Stages of the Process of Regime Transition

Note: See the text and the glossary for the definition of these terms. Liberalizations are not considered part of implementation in this model. The latter is utilized in connection with events occurring after breakdown. The process may include the installation of several caretaker governments, each of which may address different aspects of the agenda of transition.

Note: See the text and the glossary for the definition of these terms. Liberalizations are not considered part of implementation in this model. The latter is utilized in connection with events occurring after breakdown. The process may include the installation of several caretaker governments, each of which may address different aspects of the agenda of transition.

The installation of a new government creates a more appropriate context in which to begin implementing a process of transition that will change the nature of the regime. Use of the future tense is fully intended here for regimes are not installed—they must be inaugurated, and this requires time and effort. In most of the cases reviewed here, the governments installed after breakdown have contented themselves with restoring the rule of law and implementing the electoral timetable of the transition. Only in the case of Portugal does one find a major attempt on the part of a transition government to address an agenda of major socioeconomic changes. Several governments may be installed between the breakdown of a regime and the crystallization of a different one. Thus, there are as many empirically different varieties of transitions as there are logical possibilities.

The term implementation describes how the protagonists of the transition address the different aspects of the transition's agenda. The substantive and procedural aspects of that agenda are presented in Table 1.1. Implementation does not imply or require the presence in power of a benevolent actor capable of extraordinary statecraft. If anything, the evidence suggests that implementation is more a "muddling through" than an epic story. In addition, the protagonists of a transition seldom fit the mold of the philosopher king—Juan Carlos de Borbon is the closest example one finds—and tend to be relatively obscure politicians who grow in stature—a Raul Alfonsin, for example—scheming authoritarians trying to save the day, or dour, taciturn military officers trying to avert disaster. Furthermore, obstructionists (obstruccionistas) and aperturists (aperturistas) are roles played by the actors, not metaphors for heroes and villains.

One problem with usage of the term implementation is that it refers to a competitive situation in which democratic rules are introduced into a context that remains very authoritarian.4 Another is that implementation may begin as part of a reequilibration strategy of liberalisation that was not designed for a genuinely democratic outcome. In addition, in most of the cases reviewed here implementation of the electoral agenda is what precipitated the endgame of the transition. Basically, no one is fully in charge, and the outcome of the transition depends on how its protagonists utilized their resources to implement their own versions of transition. This being the case, we must assume that implementation will be conflictual. But conflict is reduced dramatically past the point of the endgame of the transition. The endgame is that relatively short, complex, and crucial episode of the transition in which the balance of power changes decisively in favor of the aperturists following a confrontation with the obstructionists. The timing of the endgame is the most relevant determinant of the length of the transition. Our evidence shows that implementation is very similar in all cases once the endgame has taken place. This similarity reduces the utility of a typology of transitions based on stages.

Installation—and subsequent implementation—may lead to the inauguration of a democratic regime. By this I mean the crystallization of a pattern of relations among society, political community, government, and state that conforms to the democratic blueprint and results from the installation of a government committed to democratization. The weakness of these inaugurations may be related directly to the outcomes of implementation. For example, in South America (1) judicial restorations, for the most part, have not included prosecution and conviction of those primarily responsible for

TABLE 1.1

Procedural and Substantive Aspects of the Agenda of Transition

Procedural and Substantive Aspects of the Agenda of Transition

| PROCEDURAL ASPECTS | SUBSTANTIVE ASPECTS | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Restoration of the rule of law | Credibility and authenticity of the transition |

| a. | Government acting consistently within the law | Who, in effect, is the government? |

| b. | Judicial restoration Government not abusing power Government acting within the limits of its own legality Amnesty Account for the disappeared | Legitimacy of the transition End of Arbitrary rule Opposition actors decide to participate Identity of beneficiaries Clarification of circumstances and sanctions |

| 2. | Constitutional Revision | Adjustments deemed necessary to relations among state, society, government, and political community |

| a. | Reform of the state | Governability Democratization of capitalism Respect for basic rights |

| b. | Review of the economic model | Balance between public and private sectors Property relations |

| c. | Formula of representation | Inclusiveness of the political community |

| d. | Ideological space afforded | Incorporation of the Left and of antidemocratic actors |

| e. | Presidential model | Civilian supremacy Executive-legislative balance |

| 3. | Electoral Process | Identity of the government |

| a. | Basic electoral statute | Characteristics of the contest |

| b. | Electoral timetable | Ability of the parties to organize the public |

| c. | Validity and efficacy | Degree to which outcome is favorable to democratization |

| 4. | Transfer of Power | Can the government attempt to |

| a. | Timing of endgame | ...inaugurate and/or consolidate democracy? |

| b. | Degree to which (1) and (2) require further action |

abuses of authority under the military governments; (2) constitutional reform has not altered the political economy; (3) the installation of a republican government and the inauguration of a democratic regime may not have put an end to military interventionism; (4)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- PART ONE: THEORETICAL AND COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES

- PART TWO: SOUTH AMERICAN CASES

- PART THREE: ON GOVERNABILITY

- Glossary

- About the Contributors

- Index