![]()

1

Introduction

The industrial-scientific revolution in the design, production, and use of technology had traversed two centuries before industrial societies turned to the comprehensive management of the technological hazards attendant on that revolution. Whether one dates the beginnings of this effort to the early warning popularized in Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962, the mass public outcry of Earth Day in 1970, or the classic paper of Chauncey Starr (1969), the movement is less than a quarter century old. Discernible innovations in the way society handles technological hazards are under fifteen years old, but the profound nature of the changes in attitudes, institutions, and activities may well hail, in retrospect, a revolution no less impressive than its predecessor.

It is always difficult to take stock in the midst of rapid change. Studies have concentrated on two features—the emergence of the environmental, consumer, and personal-health movements and the societal response in the form of legislation, governmental agencies, and regulations that cover the varied domains of technological hazards. Recently, attention has focused on changes in judicial processes, their roles in monitoring administrative performance, and more important, in providing compensation to victims as well as in deterring negligence (Huber 1986). But perhaps the most profound and least-recognized changes have occurred in the corporate world.

That world's management of hazards is uncharted terrain. This is so partly because the corporate world has a deep-seated reluctance to submit to external inspection or to encourage introspection. Moreover, several corporate biases come into play. In graduate schools of business and in economics departments, students of corporate activity focus primarily on managerial strategies related to the "bottom-line" measures of profit and efficiency. Graduate schools of business harbor few professors of hazard management. Conversely, social scientists feel more comfortable with the unfettered research possibilities in studying the more accessible domains of governmental or public behavior. Others see hazard management as the incidental outcome of conflicting forces in capitalist society. Finally, accounts of hazard management have dwelled upon corporate failures and abuses (Johnson 1985).

A prevalent view has it that hazard management in corporations is fundamentally flawed by the conflict between safety and short-term profit, that without the pressure of regulation, continuous public scrutiny, and liability law, corporations inevitably remain "bad actors" who will undermine public and occupational health and safety. Evidence of callous behavior is easy to document, particularly among smaller, "marginal" firms with minimal investments in, and concerns with, health and safety. Failures in hazard management show up in poorly educated, illegal immigrants who handle highly toxic chemicals in poorly ventilated work areas, workers exposed for years to asbestos or cotton dust, or "midnight dumpers" of chemical wastes that eventually contaminate ground water (OTA 1983). In other cases, companies have acted within the safety context that operated at the time, only to be greeted by the changed values and recriminations of a new generation of publics and workers.

But abuses and failures do not capture the whole spectrum of corporate hazard management. Some corporations not only have at their disposal extensive resources for hazard analysis and management but have conscientiously organized to do an effective job. For these corporations, government regulation is a continuing prod (and sometimes nuisance) that the internal apparatus for risk management must endure. Oftentimes, these corporations have risk-reduction and safety goals that exceed those embodied in government standards and that find support within the organization not only because they contribute to a safer workplace and healthier consumer but because they provide long-run stability, fewer liability threats, a good corporate image, and even (occasionally) a competitive edge over firms that lack the resources to mount similar efforts.

In short, corporate hazard management is a complex subject prone to oversimplification. Simplistic theories and stereotypes are likely to have limited application, and governmental regulation has different impacts and roles in different corporations. Thus, a timely examination of hazard management in large corporations is needed to profile how they actually go about the task of managing technological hazards and making trade-offs among conflicting objectives and constraints. Such empirical scrutiny can help to test the accuracy of prevailing assumptions and stereotypes, as well as to complement the already flourishing literature of comparative case studies of the public sector.

Then, too, structural considerations prompt an examination of corporate hazard management. Previous studies of 93 technological hazards (Hohenemser, Kates, and Slovic 1983) have suggested that the management of hazards usually works best at stages of design and choice of technology. Decision making at these points almost invariably lies in the hands of industry. Thus hazard makers are also potentially the most effective hazard managers. The rub comes in creating the reality of corporate responsibility in a milieu of corporate pressures to avoid hazard management costs and to externalize costs on society as a whole.

Finally, the scope of corporate investment—notably over the past decade—in hazard assessment and safety analysis holds particular promise. In many cases, these resources are so extensive as to parallel or exceed the resources available to government regulators. Enhanced public access to such resources would enlarge substantially society's total capability for dealing with hazards of all kinds. The chemical industry's massive investments in screening and testing chemicals, for example, would make an extensive addition to the public resources in the field. It is worthwhile, therefore, to explore potential pathways for gaining access to these corporate resources and for bringing industry research and findings, suitably sifted and separated from proprietary information, into the public domain.

Accordingly, five years ago the Hazard Assessment Group at Clark University's Center for Technology, Environment, and Development (CENTED) set out to explore the possibility of studying corporate hazard management. The group wet its feet with a site visit to a major chemical producer. But two years elapsed before the clearing away of other research commitments allowed the planning of a full-fledged study. The planning process soon ran up against the problems of securing funding and gaining access to corporations. Major public agencies were reluctant to disburse funds for the study of private industry, and the Clark group felt uneasy about tapping private industry for support to study private industry. Fortunately, a modest grant from the Russell Sage Foundation came through to permit initiation of the exploratory research.

The long-term goal aims to answer a pivotal question: Given the inherent conflict of interest in corporate roles between enlarging profit and securing safety and given the apparent limits to society's capability to regulate industrial hazards, how can society more effectively tap the competence and experience of industry in managing technological hazards? To begin to tackle this ambitious question, this exploratory study addresses three more modest objectives:

- to profile the current structure of hazard management in selected corporations

- to analyze in depth the generic institutional activities in which corporations engage and the extent of corporate resources that support such efforts

- to evaluate, where possible, the outcomes of these efforts, noting the sources of success and failure.

To foster a better understanding of the current practice of hazard management in large corporations, the following chapters present case studies of five specific corporations. The researchers sought cooperation from corporate officials and offered reasonable protection of the corporation's vital interests in areas of liability, proprietary information, and the like. In general, the research sought information on the organization, scope, priorities, and substance of hazard-management activity as well as the processes and resources for arriving at corporate decisions and resolving internal conflicts—buttressed, wherever possible, by empirical data and examples. The researchers, in return, strove to describe their findings objectively and in a comparative framework, to permit corporate review of (but not changes in) the analyses, and to refrain from judgments for which the data base was inadequate.

For three of the detailed case studies (MACHINECORP, PETROCHEM, and PHARMACHEM), the agreements stipulated that the corporation (or plant) and its locations) remain anonymous. One of these companies (MACHINECORP) eventually decided to terminate its participation in the study. Two other cases (Volvo and Rocky Flats) carried no requirements for anonymity. One case (Bhopal) entailed extensive use of a voluminous public record as well as a visit to corporate headquarters and a subsequent meeting with corporate officials. The remaining cases involved site visits, briefings by hazard managers, or both.

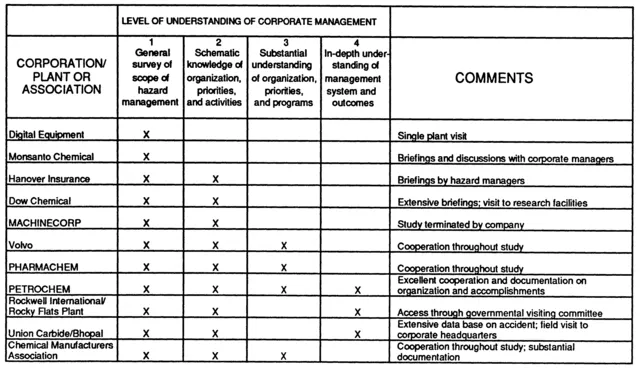

A case study of the Chemical Manufacturers Association, field visits to Digital Equipment Corporation and Monsanto Chemical Company, and interviews with representatives of a regional insurance company rounded out the study. Our general discussion includes the results from these efforts: Table 1.1 provides an overview of the case studies and indicates the authors' collective judgment as to the level of understanding that the research achieved.

The Study Sample: Large and Wealthy Corporations

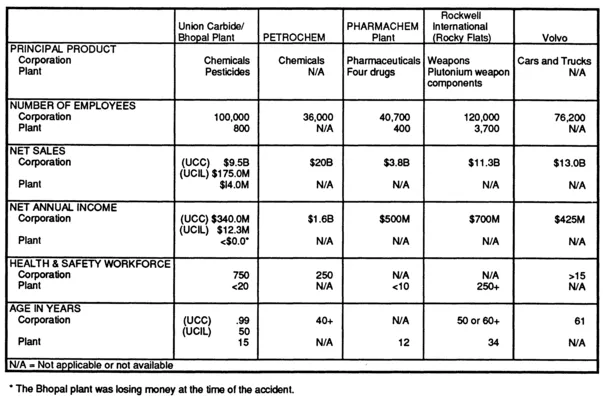

As Table 1.2 shows, the corporations studied are relatively large, with total employment ranging from 20,000 to 100,000, and annual incomes falling in the range of $.34-$ 1.6 billion. In three cases (Union Carbide, PHARMACHEM, and Rockwell International), the study focussed on individual plants with specific missions. Even these plants are large, with employment ranging from 400 to 3,700. All of the five corporations studied in detail are involved in modern technology in which innovation, automation, and (with the exception of the Rocky Flats) strong competition and profitability play dominant roles. None of the five corporations was in financial difficulty (although the Union Carbide plant at Bhopal was having problems), and one of the plants (Rocky Flats) operated on a government financed cost-plus basis with essentially no limit on hazard expenditures. Although the ages of the corporations, ranging from 40 to 99 years, indicate mature institutions, the younger ages of particular plants (12-34 years) reflect recent innovation. Even the oldest plant studied (Rocky Flats) has undergone extensive rebuilding and renovation in the past five years.

The study sample, then, is highly skewed toward one end of the spectrum of corporations. Clustered in this space are the leaders, corporations with state-of-the-art programs for managing hazards. Indeed, except for the Bhopal calamity, the sample is devoid of clear failures in management or "worst-case scenarios" come true. It is essential to bear this in mind.

Uneven access to corporations and to hazard managers rendered the five case studies somewhat incommensurate. For the three corporations (PETROCHEM, PHARMACHEM, and Volvo) that provided a high degree of access, the study yielded extensive information about the organization of hazard management and much less about the structure, consequences, and assessment of hazards. In the case of limited access (Rockwell International), the analysis focuses upon the hazard, its potential consequences, and risk assessment and presents relatively scant detail about the organization of hazard management within the corporation. For the Bhopal plant, it was possible to tap both a general understanding of the

Table 1.1 OVERVIEW OF CASE STUDIES

Table 1.2 VITAL STATISTICS OF THE CORPORATIONS/PLANTS STUDIED

corporate management structure and a detailed data base on the causes and management of an industrial disaster.

Perhaps the most striking example of successful industrial hazard management is the Volvo Car Corporation, which occupies a unique niche in innovating safety in the automobile industry. Long before Detroit awoke to the fact that safety sells, Volvo stood virtually alone in the industry in promoting and advertising a vigorous corporate effort in safety design. A pioneer in installing safety belts before they were required, Volvo introduced many other safety-design features before they became standard elsewhere in the industry. Volvo supports efforts to assure vehicle safety through a unique feedback system, an accident-investigation effort that sends company investigators scurrying to all accidents within a certain radius of company headquarters. The company had also integrated hazard management into overall corporate quality assurance. Organizationally, health and safety at Volvo play a role less visible and distinct than at PETROCHEM and Rockwell, but that is probably appropriate for an industry where product safety is best achieved through design and quality control.

Three corporations—PETR...