- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Anthropology And Development In North Africa And The Middle East

About this book

This book documents the function of social science analyses in the identification and evaluation of development programs in the Middle Eastern and North African countries. It demonstrates that anthropology and social sciences have a good deal to contribute to the understanding of domestic economies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Anthropology And Development In North Africa And The Middle East by Muneera Salem-Murdock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Brokering Social Science in Development: Experiences in Morocco

Alice L. Morton

Introduction

Anthropologists have given a good deal of thought to the roles they play in international development, including that of broker or representative for the generally unempowered potential beneficiaries or losers in development projects. One issue concerns the ability of foreign anthropologists from the First World adequately to understand the cultures they study and to speak in their defense. Related to this is a concern about the role of the indigenous anthropologist vis-à-vis the development process in his or her own country (cf. Asad 1975; Fahim 1979). A move toward enhancing indigenous socialscience involvement has been made, especially in Latin America and in South Asia, and the question of the role of expatriate anthropologists and related foreign funding permeates debate among Africanists and those working in the Middle East. In North Africa, a number of local social scientists have expressed their aversion even to involvement with such organizations as the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) and the Ford Foundation (Zghal 1986).

From the mid-1970s on, anthropologists at the Agency for International Development (AID), which at that time had just hired a new cohort of noneconomist social scientists, became especially concerned about these matters (see Hoben 1980; Horowitz 1980; Practicing Anthropology 1980-1981: inter alia). While they gave most weight to the values and ethics questions of participation by Western anthropologists in development, they also looked for ways in which indigenous anthropologists could be integrated into the process. Where this was actually done, it was frequently at the initiative of an individual social scientist in AID, whether at the Washington headquarters or in the field. One example of an attempt at an institutional level to enhance local social-science capacity, however, comes from two projects funded by the AID Mission in Morocco.

Background

The projects in question, Dryland Agriculture Applied Research (DAARP) and the Agronomic Institute Project, were both early examples of AID foresight in attempting to involve local social scientists in agricultural and rural development. The relationship between the two projects has varied over time, as has the tenor of relations between their respective hostgovernment counterparts, l'Institut National de Recherche Agronomique (INRA) for DAARP and l'Institut Agronomique et Vétérinaire Hassan II (IAV) for the "Institute" project. Since 1973, AID has provided, through the University of Minnesota, funds for faculty and institutional development at IAV. Junior faculty from IAV were trained in the United States in agricultural sciences and research techniques, and a few social-science-oriented faculty trainees were also included. The goal was to develop a U.S. land-grant type of institution along Moroccan lines.

DAARP, whose design began in 1976, preceded a later move in AID in the 1980s to design farming systems projects that integrated some socialscience input with agronomic research and extension (see Cernea and Guggenheim 1985). The project goal was "to develop a permanent applied research program aimed at increasing farmer productivity" (USAID/Rabat 1977). This included establishing a dryland agronomic research program within INRA to identify suitable farming equipment for small farmers, and establishing a socioeconomic research program at IAV to provide a better understanding of the current behavior of dryland farmers and, thus, a basis for more effective research and extension programs. DAARP also included a substantial component for training Moroccans from INRA in agricultural sciences in the United States. The socioeconomic research program was implemented under a separate grant to IAV's Department of Human Sciences.

By early 1982, IAV had finished carrying out an initial round of studies under the DAARP-funded grant. Due to contracting delays, the research agronomists, fielded by the MidAmerica International Agriculture Consortium (MIAC) with the University of Nebraska as lead institution, had only just arrived. Thus, for once, the social scientists were ahead of the game and had begun producing results that were supposed to provide background to the agronomists as they began to design their experiments on-station and on-farm.

Despite this seemingly favorable situation, the non-French-speaking MIAC agronomists indicated no interest in the IAV socioeconomic research results. Among those members of the AID staff in charge of monitoring the grant, a suspicion arose that this might be because the research somehow was not being done right, or presenting the right kind of results. In part, this was caused by a pervasive lack of French language skills among the AID personnel, but those who did scan the French language reports felt that what they were reading was some sort of foreign social science, not the analogue of American agricultural economics and rural sociology that they had expected.

The Basis of the Broker Role

As a result of this concern, the USAID Mission's Agriculture Office asked me to review the results and revise the scope of the socioeconomic research component of the DAARP. Under the same five-month contract, I was also asked to develop a beneficiary profile, based on these data, for a potential new project to be located elsewhere in Morocco. I returned in 1983 with other contractors to evaluate and redesign the entire project so that it could be extended for another five years. At the same time, I led a team to evaluate and redesign the institute project with LAV, thus becoming familiar with the other departments there and with Institute senior management. Subsequently, I worked on the design of the extension of that project (1983) and a special evaluation of that extension (1988). This combination of contracts has permitted me to follow the social-science and institutionbuilding dimensions of a series of AID-sponsored interventions over six years but always as a "proximate outsider" rather than as a permanent official of either of the governments concerned.

Before I was given the first contract in 1982, I was taken to IAV to meet Professor Paul Pascon, then head of the Department of Human Sciences, who had collaborated in developing the scope of work for the IAV socioeconomic research with AID. This fairly unusual step for a USAID mission to take—I was clearly there to pass his inspection—indicated the respect in which the mission staff held Professor Pascon, a French-born social scientist who took up Moroccan citizenship at independence (and who has died recently). While I passed muster sufficiently to be given the contract, it was not until I returned to Morocco on the successive contracts that I felt I had achieved some credibility with Professor Pascon and his colleagues.

The Socioeconomic Research Program

The recommendation for the IAV socioeconomic research program had been included in the project-design study carried out by a first MIAC team, including a senior rural sociologist from the University of Missouri. This team had recommended a broad outline for socioeconomic studies and suggested that a U.S. sociologist be dispatched to Morocco to assist IAV in developing the program. The team was expressing its awareness that research methodologies and standards were likely to be different at IAV from those common at U.S. universities, especially regarding quantification of research results.

The mission did not accept this recommendation, partly at least because of strong objections from IAV, which felt that an American presence in the Department of Human Sciences was neither necessary nor appropriate—this, despite their willingness to have U.S. academic technical assistance from the University of Minnesota in other departments under the Agronomic Institute Project. The "human scientists," however, appeared strongly to resent the implication that they should do social science research a l'améicaine, and that they needed help to do so. This situation persists today (USAID/Rabat 1988).

Funding for the program took the form of a grant rather than a contract. In AID's terms, this meant that IAV—and especially Professor Pascon as Principal Investigator—had broader latitude in managing the activity than would have been the case under a contract.1 As the language of the grant was quite general, the AID mission tended to rely, de facto, on Professor Pascon and his colleagues to define the methodology to be applied. This was especially true as there was no social scientist in the AID mission. From 1980 to early 1982, then, the mission exercised only very limited supervision over the grant, making little effort to assess the direction the research was taking.

In fact, by 1982 Professor Pascon had developed a team approach to the work, and had involved some young researchers from outside IAV, as well as a number of Third Cycle (roughly M.S. level) students. As part of their course requirements, these students were to carry out original research where possible, and the AID funding provided much-needed support for these efforts. By 1986 some 23 students had received partial funding for their degrees under the DAARP grant (Winrock 1986).

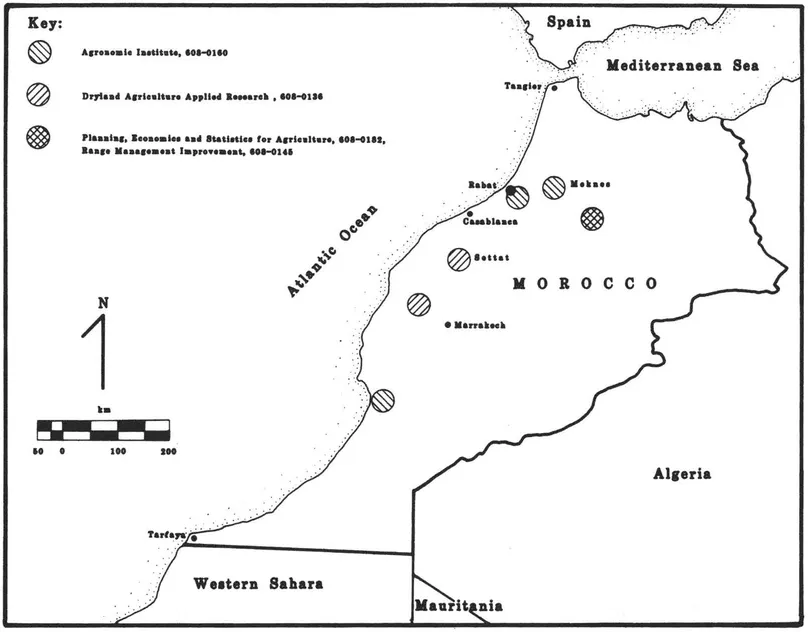

The broad range of studies included both qualitative and quantitative approaches. On the more qualitative side was a study of rural employment and migration. At the more quantitative end was a survey of nearly 2,000 households that was intended to lead to the development of a data-based typology of farms in the project area. Also included were several soilmapping efforts, which took a holistic approach to understanding the area and its inhabitants. These studies, together with other efforts funded separately by the Institute, became known as Projet Chaouia, as they were concentrated in the Haute Chaouia region (see Figure 1.1).2

The core element of Projet Chaouia, a longitudinal study of 50 farms drawn from the initial sample of 2,000, was intended to describe and analyze changes in the whole-farm system, and thus to examine in detail what risks these farm families faced and how they coped with them. The study was under way by 1982, and from IAV's point of view, the socioeconomic research program was generally going well. Students and faculty were engaging in what they saw as relevant applied research in the field, using a variety of techniques and exploring a broad range of topics. Relatively modest funding was being used to support a large number of junior researchers at what was, after all, essentially a teaching institution.

The reports were slow in arriving at AID, however, and the mission felt exposed. On the one hand, they suspected that IAV might be carrying out its own agenda under the grant, while at the same time the MIAC scientists couldn't assess the work for the mission because of the language barrier. The kind of close association between counterparts that had been envisaged by the MIAC project designers was clearly not taking place.

FIGURE 1.1 Morocco, Showing the Project Areas. Source: AID/Washington.

Bringing in the U.S. Social Scientist

In order to address some of these concerns, the Agriculture Officer contracted with me, a social scientist with considerable experience translating academic anthropology from French to English, to assess the data generated by the socioeconomic research program and to synthesize them in English for further assessment by AID, and for the ultimate use of the MIAC agronomic researchers. My contract provided five months to carry out these tasks, to conduct a literature review, and to develop a beneficiary profile for a future rainfed-agriculture project elsewhere in Morocco. Given AID practice, five months was a rather generous amount of time for such a contract, a further indication that the mission was taking the socioeconomic aspects of the project seriously, even though it had begun to doubt whether this would ultimately be a good investment.

The Beneficiary Profile—Looking for the Data

When I arrived to carry out my scope of work under this contract, I was presented with photocopies of twelve IAV Third Cycle theses, the soils mapping studies, a copy of Professor Pascon's encyclopedic two-volume study of the Haouz (1979), and some fugitive literature on Moroccan society and culture. This contrasted sharply with my prior experiences in other missions, where social science and other literature had been in short supply. The USAID/Rabat library is one of the best mission libraries I have worked with, for it has consistently ensured, over the years, that local journals as well as books published in and outside Morocco have been obtained and maintained. Thus, my initial belief that I would have more than enough data lulled my concern that I did not have Arabic and that I was not a specialist in the Maghreb. In the past, I had become familiar with some of the better-known English-language anthropological literature on Morocco, especially the work of Gellner (1969) and Geertz et al. (1979). (Part of the subsequent problem was that I continued to seek ethnographic material of this sort for the Chaouia and neighboring regions.)

Armed with U.S. and U.K. training in sociology and anthropology, including field research, six years of experience as an AID officer, and prior experience with international social science through the SSRC, I felt that I should do all right as long as the mission and the local social science community continued to help me become better informed. Further, it seemed at first that some amount of "rapid reconnaissance" field work would adequately complement the secondary source material, although the mission director had initially stressed that the effort was to be mainly literature based.

Soon after beginning to read, I became extremely uneasy, for the more I read, the less information I found to answer the questions framed in my scope of work. And yet, the scope of work seemed to be fairly sensibly put together from an anthropological point of view. It asked for some social history of the area, some data on kinship and other dimensions of social organization on women, and on social mobility. Surely, I thought, in all this wealth of documentation, I should be able to find the data to weave into my beneficiary profile. So I kept reading.

When unease turned into anxiety, I went to see Professor Pascon. Explaining that I did not seem to be finding any ethnographic data, I asked him to suggest sources other than those I already had. We discussed what I meant and what I thought I needed, and he gave me access to his index of materials and, essentially, to his library. I was still somewhat at a loss, for nothing I read met the needs created by the scope of work or by my own definitional schema. I next went to the National Library to see what some of the older French colonial sources might provide. Short of coming on an unexpected wealth of new materials, however, I felt I would definitely have to renegotiate and narrow my scope of work. Ultimately, the scope of work was revised to restrict the beneficiary profile to Haute Chaouia (see Morton 1982).3

As the weeks passed, I continued to look for other data in the IAV reports (which covered the territory from household food consumption through regression analysis of the relation between land tenure and average farm size), and I began to ask to go to the field. Obligingly, I was invited along on various field trips, including to Settat, the main site of project DAARP itself, housing the new Aridoculture (dryland agriculture) Center being constructed with project funds for INRA and expatriate agricultural research staff. I usually traveled with US AID staff and other contractors, but sometimes with IAV staff either with or without AID personnel. Some of the more memorable visits were to other areas of the country, since the idea was to give me a fairly broad exposure that would, in a sense, complement the literature review and the initially broad scope of work to which I was responding. I did not, however, visit any farmers. When I asked the USAID Agriculture Officer the reason, he replied that traditional Moroccan male farmers would not talk to a woman. This was despite known and published fieldwork by expatriate women social scientists.

Finally, one of the IAV senior staff arranged for me and an AID colleague to visit a large "modern" farmer near Fez. Since I had been reading a long and informative thesis on agricultural mechanization (Zagdouni 1981), I was very pleased to be able to see some in action at this large farm, which produced cereals for sale as well as doing seed multiplication. Better yet, all the various types of land tenure and sharecropping arrangements that I had been reading about were represented on land managed by this one farmer and his sons. Things were looking up. The local representatives of the Ministry of Interior dropped by for tea, and a lively discussion ensued about the future of agriculture in Morocco, and on how the American agricultural revolution had occurred. This gave me an immediate sense of the integration of the local power structure and its views on agriculture, the big cooperatives, and production problems. The orientation seemed definitely toward following the U.S. example of mechanization, larger farm units, and modernization. I determined to create a beneficiary profile that might bring some of this to life for the Chaouia area, but first I had to turn my attention to redesigning the socioeconomic research component of the DAARP in consultation with ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Brokering Social Science in Development: Experiences in Morocco

- 2 Slash-and-Burn Cultivation, Charcoal Making, and Emigration from the Highlands of Northwest Morocco

- 3 Farm Size and Agricultural Credit in Morocco: Correcting Distorted Information in the Development Process

- 4 Water-User Associations in Rural Central Tunisia

- 5 Household Production Organization and Differential Access to Resources in Central Tunisia

- 6 Development in Hammam Sousse, Tunisia: Change, Continuity, and Challenge

- 7 An Anthropologist's Contribution to Libya's National Human Settlement Plan

- 8 Developing Egypt's Western Desert Oases: Anthropology and Regional Planning

- 9 Agricultural Development and Food Production on a Sudanese Irrigation Scheme

- 10 Advocacy in a Bedouin Resettlement Project in the Negev, Israel

- 11 Rural Development and Migration in Northeast Syria

- 12 Doing Development Anthropology: Personal Experience in the Yemen Arab Republic

- 13 Land Use and Agricultural Development in the Yemen Arab Republic

- 14 The World Bank and the Çorum-Çankiri Rural Development Project in Turkey

- 15 Tradition and Change Among the Pastoral Harasiis in Oman

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Index