- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book of selected research papers, originally presented at the "Symposium of Fragile Lands of Latin America—The Search for Sustainable Uses," presents some fresh evidence of the viability of a few "non-conventional" strategies for natural resource development and management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fragile Lands Of Latin America by John O. Browder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Économie & Développement durable. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Fragile Lands and Technology Transfer: Conceptual Frameworks

1

The Geography of Fragile Lands in Latin America

Introduction

The nature and problems of fragile lands in relation to agriculture in Latin America recently have been brought into focus by international development institutions (see Gow, this volume). What I want to do here is to define, categorize, and map fragile lands in Latin America, and briefly present some relevant concepts and comments.

Definition

“Fragile Lands” are lands that are potentially subject to significant deterioration under agricultural, silvicultural, and pastoral use systems. Indicators of deterioration include both short-term and long-term declines in productivity, negative off-site impacts, and slow recovery of water, soil, plant, and animal resources following disturbance (based on Bremer et al., 1984:3).

I have added the word “potential” in the definition to emphasize the fact that land is not naturally fragile. It is only fragile in terms of (1) specific types of use systems, and (2) specific intensity and frequency levels of usage. For example, steep slope lands are not particularly vulnerable to erosion if they have been terraced. And a small plot of tropical forest is not very fragile if it is only farmed one year out of one hundred by slash and bum methods. There are only potential fragile lands, with the degree of fragility varying with the nature of use in relation to the type of environment. Otherwise we get into deterministic ways of thinking about the environment (as with the concept of “agricultural potential,” which does not exist independent of culture). The environment is neutral. It is human beings who give it attributes through the ways they interact with it.

Fragility is a relative concept. All environments are subject to deterioration under human use. Thus it is more appropriate to refer to “less fragile lands” rather than “non-fragile lands.” Also, different components of environments are potentially more fragile than others. Finally, environments are not naturally stable but change both slowly and very rapidly, and degree of fragility varies accordingly.

The concept of fragility is related to but different from that of “marginality,” which refers to lands which have significant environmental constraints (requiring special environmental management technology) and/or low productivity or accessibility.

Tropical lands tend to be particularly fragile because process rates for productivity, decomposition, mineral cycling, succession, erosion, etc. are generally higher in the tropics than in temperate regions (Famworth and Golley, 1974:x-xi). On the other hand, cold lands are potentially very fragile for the opposite reason—very slow process rates.

Classification, Distribution, and Extent

Setting these points aside, I have attempted a simple classification consisting of seven categories of fragile lands based on slope, climate, and vegetation (Table 1). The main stress factors are indicated for each (see photographs).

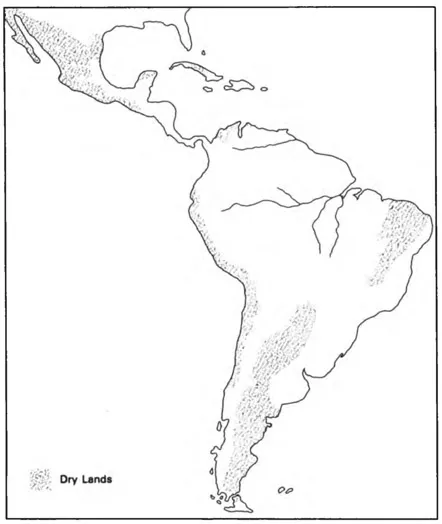

Figures 1–4 show the approximate geographic distribution of the seven categories of fragile lands. Only large units are shown. One is immediately impressed by the fact that most of Latin America can be considered fragile. The largest non-fragile, or less fragile, lands are the temperate grasslands and forests of southern South America.

The approximate areas covered by each fragile land category are shown in Table 2. Fragile lands account for 87% of the total land area of Latin America. Within this area there are unmeasured pockets of less fragile land, which amount to only a small percentage of the total. The less fragile temperate lands of southern Brazil, the Argentine pampas, and Uruguay total only about 13% of the land area of Latin America.

The only non-usable lands considered here are the cold lands above the tree and grass lines where frost is too severe for crops, pasture, or trees. These areas are scattered in the Andes and southern tip of South America and are not mapped. It may appear to be an extreme statement to maintain that all other lands are usable, but such is indeed true, depending on the technology and crops available and the labor or capital expenditures people are willing or able to make for subsistence

Table 1 Categories of Fragile Lands and Their Stress Factors

| Category | Stress Factors |

| | |

| First group: Flat to gently sloping terrain (primarily lowlands) | |

| 1. Tropical forests (tierra firme or interflueve) | Soil fertility (low initially; readily depleted once forest is removed) Pests (weeds, animals, insects, diseases; can cause field abandonment even on superior soils) |

| 2. Tropical savannas (well drained) | Soil fertility and structure Pests |

| 3. Wetlands (subject to seasonal or permanent flooding: savannas, floodplains, swamps, lake edges; not always particularly fragile) | Excessive flooding (height and/or duration) |

| 4. Dry lowlands | Aridity (highly variable) Salinization (salt accumulation under irrigation) Inadequate flooding (height and/or duration in river valleys) Desertification (from vegetation degradation) |

| Second group: Moderate to steeply sloping terrain (primary highlands) | |

| 5. Montane tropical forests | Slope (vulnerability to erosion especially great due to high rainfall) Soil fertility (extremely variable) Pests |

| 6. Dry highlands | Slope Frost Aridity |

| 7. Rainfed highlands | Slope (vulnerability to erosion especially great due to high rainfall) Frost |

Plate 1 Tropical forest along the Amazon near Iqu¡tos, Peru (M. H¡raoka, 1983; reprinted by permission).

Plate 2 Tropical savanna (well drained), Orinoco Llanos, Venezuela (W. M. Denevan, 1972).

Plate 3 Flooded savanna, Llanos de Mojos, northern Bolivia (W. M. Denevan, 1962).

Plate 4 Coastal desert, northern Peru, showing a section of the Moche-Chicama intervalley, pre-lnca canal (James S. Kus; reprinted by permission).

Plate 5 Montane tropical forest, eastern Bolivian Andes (W. M. Denevan, 1961).

Plate 6 Dry highlands, Coica Valley, Peruvian Andes; note abandoned terraces on center slope (W. M. Denevan, 1983).

Plate 7 Rainfed highlands, largely cleared of forest, Colombian Andes (W. M. Denevan, 1977).

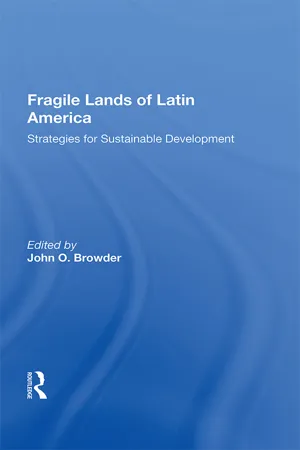

Figure 1 Map of mountains 1,000-plus meters in elevation (modified from Cole, 1965:31).

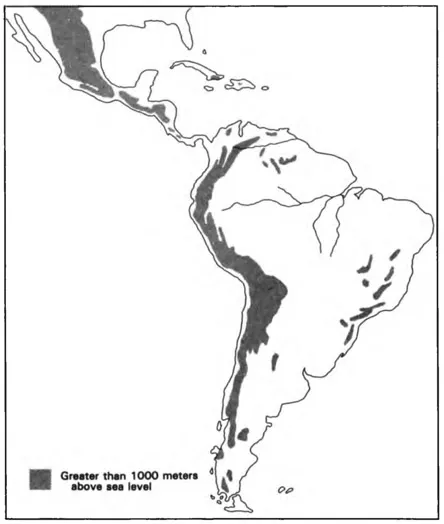

Figure 2 Map of well-drained savannas and wetlands (wet savannas and floodplains) (modified from Sarmiento and Monasterio, 1975:225).

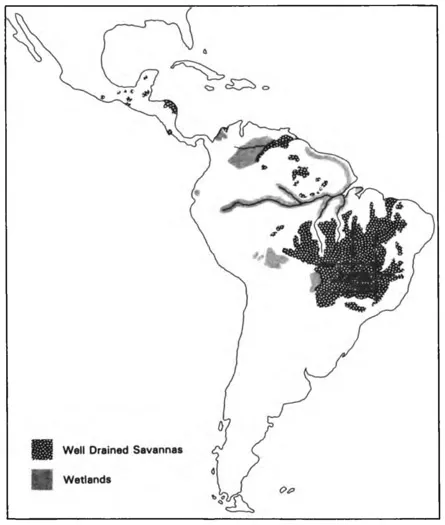

Figure 3 Map of tropical forests (modified from Cole, 1965:42).

Figure 4 Map of dry lands: highland and lowland, including dry forest, cactus scrub, and desert (modified from Cole, 1965:42).

or for market. All forest can be used. Deserts can be irrigated, depending on water availability. Steep slopes can be terraced. Swamps can be drained. And infertile soils can be fertilized. The costs, of course, may be prohibitive for permanent, sustained systems, or systems may be used which are sustainable only on a periodic basis.

Table 2 Extent of Fragile Lands

| Category | Area Covereda (km2) | Percentage of Latin America |

| | ||

| 1. Tropical forests | 7,970,000 | 39 |

| 2. Tropical savannas | 2,375,000 | 11 |

| 3. Wetlands | 665,000 | 3 |

| 4. Dry lowlands | 5,225,000 | 25 |

| 5. Montane tropical forests | 340,000 | 2 |

| 6. Dry highlands | 590,000 | 3 |

| 7. Rainfed highlands | 760,000 | 4 |

| Less fragile | 2,650,000 | 13 |

| Total | 20,575,000 | 100 |

a Modified from Cole, 1965:49. More recent estimates show lower figures for tropical forests and tropical savannas, which could raise the less fragile total to as much as 20%.

Figures are not available, but certainly a much lower percentage of the more fragile lands is cultivated compared to the less fragile lands. Furthermore, the more fragile lands are dominated by small farmers, whereas the less fragile lands are dominated by large farmers, haciendas, plantations, and corporate farms.

Management of Fragility

All the fragile land categories can be utilized under extensive management systems (shifting cultivation, sectorial fallowing, agroforestry, low density grazing) with minimal deterioration. However, all are subject to deterioration under intensive use systems. Sustained, intensive productivity generally requires significant landscape and soil modification (terracing; raised and sunken fields; water control canals, reservoirs, and embankments; and soil additives) in order to manipulate resource conditions and stress factors (slope, water availability, temperature, pests, soil fertility). Under traditional land-use systems such modifications are usually labor intensive; they are usually responses to population or market pressure; and they usually include risk-minimizing strategies which may lower productivity. By manipulating natural stress factors, such systems render fragile lands less fragile and more sustainable, many having been in place for hundreds, even thousands of years.

Modern land-use systems (based on fossil fuel inputs), in contrast, are capital intensive and the costs of landscape and resource management are often excessive in relation to economic returns (irrigation is a major exception). As a result, fragile lands may not be utilized under modern systems. Development of fragile lands needs to draw upon traditional knowledge, on labor rather than on expensive fossil fuel energy, on management improvements which increase productivity without threatening sustainability, on risk avoidance, and on environmental stability (Denevan, 1980a). Traditional knowledge is location specific, however, “and only arrived at through a unique co-evolution between specific social and ecological systems” (R.B. Norgaard quoted in Redclift, 1987:151).

A large portion of the fragile land area of Latin America is excessively dry, subject to flooding, or consists of steep slopes. As a result, special landscape engineering techniques are required before effective cultivation is possible. Three traditional techniques, each highly varied, have been utilized throughout the Americas: terraces, irrigation canals, and raised fields. All of these were important in Pre-Columbian times (Denevan, 1980b). Terrace and irrigation systems continue to the present, but raised field cultivation is now rare. Vast areas with these agriculture landforms are now abandoned for reasons that are not altogether clear, but the fragile nature of the environments involved and demographic change are clearly central factors.

Most of the papers in this volume concern land systems in tropical forests, which are particularly fragile environments since most, not just one or two, components of the ecosystem are adversely affected once forest is cleared for agriculture or pasture: soil structure, organic matter, mineral content, biota, surface temperatures, humidity, runoff, and evapotranspiration.

Relevant Concepts

Perception. People’s attitudes towards fragile lands and how and whether they are used depend on perceptions which vary culturally and individually and change over time. Some attributes of fragile lands may be perceived so positively as to outweigh the negative aspects which are then controlled by technology and high labor inputs. Alfred Siemens (1977:21) has discussed this for the wetlands of the Mayan region, considered to be miserable, disease ridden, useless swamps since early colonial times. The Maya, in contrast, found these lands to be sources of water, wildlife, and organic muck for constructing raised fields and hence prime settlement locations. The areas of prehistoric raised fields around Lake Titicaca were mapped as only usable for fishing and totora reeds by a recent land-use survey, reflecting current scientific perceptions of what is usable or fragile, and what is not.

Carrying Capacity. A difficult concept to apply, refers to the number of people that can be supported by a given environment, with a given land use system, and a given standard of living, without environmental deterioration. Fragile lands presumably have lower carrying capacities because they are readily susceptible to deterioration. This is not necessarily the case, however. Some fragile lands have some of the highest food productivities in the world, for example the chinampas in wetlands in Mexico, rice paddies on tropical soils in Southeast Asia, and irrigation systems in the deserts of Peru. However, input costs needed to farm fragile land...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Editor and Contributors

- Map of Research Sites of Contributing Authors

- Introduction

- PART ONE FRAGILE LANDS AND TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER: CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

- PART TWO STRATEGIES FOR TROPICAL RAINFOREST MANAGEMENT

- PART THREE STRATEGIES FOR SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE IN THE ANDEAN HIGHLANDS

- PART FOUR A STRATEGY FOR SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE ON DESERT STREAMBEDS

- PART FIVE RESEARCH IN PROGRESS

- Index