Unequal Developments among the Unequals

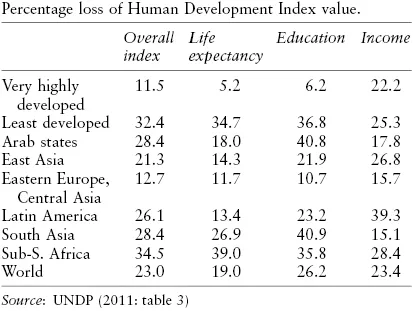

The United Nations Development Programme has recently begun adjusting its Human Development Indices13 to take into account the inequality of development. They broaden the income picture above by including the resource of education and a measure of vital inequality. On the whole, the UNDP finds that about a quarter of human development in the world is lost due to unequal distributions. While the size of this estimate may be open to dispute, the UNDP efforts make it possible to compare different kinds of inequality across the world (see table 8).

Table 8 The loss of human well-being due to different kinds of inequality in 2011 in the regions of the world.

The different kinds of inequality are unevenly distributed across the world. Vital inequality, in spite of its class resilience even in the developed welfare states, is creating most havoc in Africa, and generally in the least developed world. Unequal education is particularly striking in India, as with the rest of South Asia, and in the Arab states. China fares much better than India, because of smaller inequalities of life expectancy and of education, losing 22 per cent of its index value overall as against an Indian loss of 28. Latin American inequality is concentrated on income, in spite of a decade of equalization.

On a world scale, the rich, or ‘highly developed’, countries are the least unequal. Among the richest countries, the USA loses most of its development to inequality: 15 per cent overall, as compared to 7 per cent in Germany, 8 per cent in the UK, and 9 per cent in France and Spain. The least losses were recorded in Scandinavia and in Slovenia, at somewhat below 6 per cent. Closest to the USA in overall inequality is Southern Europe, from Portugal to Greece losing 10–13 per cent of its Human Development Index value to inequality. Adjusted for distribution, US development is slightly below that of Italy. Japanese data are missing, but South Korea comes out somewhat worse than the USA, due to the most unequal educational distribution among developed countries, which seems to be largely a generational effect, caused by a recent enormous expansion of higher education.

In Ibero-America, the worst losses were recorded in Bolivia and Colombia – a third of the Development Index – due mainly to enduring income inequality. But it is worth noticing that the region's extremely unequal income distribution coexists with considerably less in-equality of life expectancy and education. In the most unequal countries, Haiti and several African countries, from Namibia to the Central African Republic, a good 40 per cent of the already low average development level is lost to inequality.

Internal national differences in human development are huge. For example, the ratio between the Human Development Index (HDI) of the richest and of the poorest quintile in India (in 1997–9) is about the same as that of the national US HDI to the national Indian HDI in 2011. According to the estimates of Michael Grimm et al. (2009: table 1), the level of human development enjoyed by the richest fifth of the people in poor countries like Kyrgyzstan, Vietnam, Indonesia and Bolivia is on a par with, or higher than, that allocated to the poorest fifth of the United States. In Brazil, 60 per cent of the population live on a higher level than the poorest fifth of Americans (data refer to circa 2000). The figures of Grimm et al. are empirically derived estimates, produced with great scholarly ingenuity, but should be taken as indicators, rather than demonstrated truths. Following UNDP methodology, these estimates discount increases of income, which means giving more weight to health and education. But they do highlight a very important aspect of contemporary world inequality, often obscured by GDP-focused comparisons: intra-national inequalities can be stunningly wide.

Life expectancy differentials illustrate this very well. Around 2010, the lives of Swedish males in the upper-middle-class municipality of Danderyd (a suburb of Stockholm) were on average 8.6 years longer than those of fellow citizens in the far north, working-class and small peasant municipality of Pajala (Statistics Sweden 2011). That is slightly more than the national difference between Sweden and Egypt (UNDP 2011: table 1). In the UK, the life-gaps are even larger, as we noticed for London above and as we shall see further below.

The UNDP does not estimate existential inequality, but it does have a gender inequality index: a composite index of maternal mortality and adolescent fertility, secondly of secondary education and parliamentary seats in comparison with males, and thirdly of relative labour force participation rates. Viewed in this way, current gender inequality in the world looks like table 9: the lower the index, the lower is inequality.

Table 9 Gender inequality in the world, 2011

Source: UNDP (2011: table 4)

|

|

| Very high development | 0.224 |

| Least developed | 0.594 |

| Most egalitarian (Sweden) | 0.049 |

| Arab States | 0.563 |

| China | 0.209 |

| USA | 0.299 |

| Eastern Europe & Central Asia | 0.311 |

| Latin America & the Caribbean | 0.445 |

| South Asia | 0.601 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 0.610 |

| World | 0.492 |

Composite indices are always open to debate about the selection and weighting of indicators, and the UNDP index appears to be giving more weight to gendered reproductive health than to existential gendering. The reason why the USA comes out so badly, and more gender unequal than China, seems to be due primarily to maternal mortality and adolescent births, which also explain why the UK has the same index value as China. Korea and Japan score low, together with continental Western Europe, with index numbers around 0.10–0.12, while Switzerland, Germany and Scandinavia stay below 0.1. In South Asia, India is more unequal than both Pakistan and Bangladesh, in spite of less maternal mortality, having more teenage fertility, less female parliamentary representation, and more gender-skewed secondary education and labour force participation than Bangladesh. The worst sinners against gender equality, according to the UNDP calculations, with values above 0.7, are the African Sahel countries, Chad, Mali, Niger and, further, Congo-Kinshasa, Afghanistan and Yemen. Two sub-Saharan African countries are somewhat better than the world average, Rwanda and Burundi, while South Africa stands on the world meridian.

Existential gender inequality may also be approached by investigating family norms and practices, as I have done in a historical study of sex and power in the twentieth century (Therborn 2004). Today the world's two major redoubts of male family power are sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, in both cases particularly their northern parts. According to survey data reported by UNICEF (2007: 19–20), in countries like Nigeria and Mali about two-thirds of wives say husbands alone make decisions on daily household expenditure, and alone decide whether the wife can visit a friend or a relative. In Uganda and Tanzania, this is reported by just under half of all wives, in Kenya and Ghana by about a third of all married women, down to a fifth in Zimbabwe. (South Africa was not part of the survey.) In Bangladesh, corresponding conditions are experienced by a third of women; in Morocco and Egypt by a good quarter. (The Indian survey worded its questions somewhat differently, but only a third of married Indian women said they could go alone to the market, to a health facility, and outside the community. In 2005–6, 45 per cent of Indian women aged 15–49 agreed that there was at least one specific reason for which a husband was right in beating his wife (Namasivayam et al. 2012: table 2).

Under UN auspices and domestic Feminist pressures, laws bolstering patriarchal power were scrapped in Western Europe and the Americas in the last third of the twentieth century (Therborn 2004: 100ff.). While not without influence on official norms, this global process had a much more limited impact in Africa and Asia. Arab countries, and many African countries, e.g. Congo-Kinshasa, have laws of wifely obedience and requirements of husband / father / male relative consent, for a passport for example (Banda 2008: 83ff.). A Mali government bill repealing the obedience clause was withdrawn in 2009 after conservative male opposition, although it had been passed by parliament (www.WLUML.org/news/mali-womens-rights).

One area where resurgent patriarchy and masculinism can be measured is in the sexual ratio of births, of surviving children, and of male–female life expectancy. Low fertility – an enforced public policy in China and a chosen option in other parts of the world – patriarchal/masculinist son preference, and prenatal scanning technology have recently skewed sex ratios of births in a distinctive set of countries. They have been spotted in South Asia, South Korea, China, Vietnam, in the Caucasian republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, and in the western Balkans of Albania and Montenegro (UNFPA 2011).

In India, the sex ratio of 0- to 6-year-olds has increased from a normal distribution of l04–6 boys per 100 girls in 1981 and 1991, to 109:100 in 2011 (UNFPA 2011: 15ff.). The masculinist push has been strongest in post-Maoist China, soaring to a sex ratio at birth of 120:100 in 2005, and so far stabilizing there, up from 107:100 in 1982 (UNFPA 2011: 13).

Marriages arranged by fathers and/or mothers remain important in the twenty-first century, although their exact prevalence is unknown. Such marriages are still predominant in South Asia, i.e., in India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh (Mody 2008; WLUML 2006: ch. 3; Jones 2010), a practice carried into the current diaspora (Charsley and Shaw 2006). It is widespread in rural Central Asia, in West Asia, including rural Turkey, and north Africa, and in sub-Saharan Africa. It is occurring in substantial parts of Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, backed up by permissive national or provincial law (WLUML 2006: ch. 3). Islamic law forbids forced marriages, but no active consent is required of the bride. Parental marriage arrangements remain important in China, particularly in the rural west (Xu et al. 2007; Judd 2010).

However, it is important to underline the contemporary inadequacy of the binary conception of arranged marriages and marriages of choice. Classical arranged marriages without the future spouses – or at least the bride – being consulted, have largely disappeared in East Asia (Jones 2010; Tsutsui 2010; Zang 2008), and are eroding in the other parts of Asia as well (WLUML 2006; Bhandari forthcoming). In Arab countries such as Egypt and Morocco, there is overwhelming support for the idea that women should have a right to choose their spouse, and also an overwhelming perception that this is currently the case (UNDP 2005: 263–4). Between exclusive parental arrangement and individual choice without asking your parents, there is now a crowded Afro-Asian continuum of initiatives, vetoes, negotiations, accommodations and compromises. But marriage in Africa and Asia remains a family, rather than an individual, affair.

Racism and ethnic stigmatization is the other main manifestation of existential inequality. Above, we noticed that major egalitarian existential advances were made in the second half, and particularly in the last third, of the past century, culminating in the ...