![]()

1

Introduction:

What Good is Work?

[I]f the concept of labor – which in its hitherto accepted generality has given a vague feeling rather than a definite content to its meaning – is to acquire such a definite meaning, then it requires that a greater precision be given to the real process which one understands as labor. (Simmel 2011 [1907]: 453)

It often seems as though capitalist societies exist in a state of perpetual crisis regarding the issue of work. Consider the United States, long home to the world’s largest economy and where, in 2008, a financial crisis originating in the housing sector triggered a severe and extended economic slow-down. As the “Great Recession” entrenched itself, indebted consumers cut back on spending while businesses and governments scaled back hiring and laid off employees. By 2011 the country as a whole was 12 million jobs short of the number needed to provide employment for all eligible adults – not to mention the additional 25 million people working part-time but desiring full-time work.

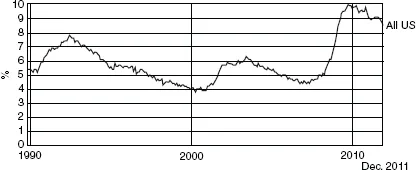

The nation’s mood was dark, to say the least. Night after night, news programs featured heartbreaking stories of hopeless job-seekers queuing up at employment agencies. Politicians from both sides of the aisle hammered Democratic President Barack Obama for his lack of a comprehensive “jobs plan” to address an unemployment rate hovering around 10 percent. While many offered different remedies for what ailed the economy, the underlying diagnosis was widely agreed upon: industrious Americans were desperately seeking work, but the jobs were simply not there.

In the midst of such a crisis, it was only too easy to forget that scarcely a decade before – in fact, during the previous Democratic presidential administration – the United States faced the opposite problem. During the 1990s, driven by a dot-com investment boom, stock markets increased in value, consumers went on a spending binge, and firms went on a hiring spree. With the unemployment rate dropping under 4 percent and a surplus of job openings, the American economy was plagued not by a lack of jobs but by a lack of workers! Especially for employers in the low-wage sectors of the economy (such as food service and home health care), it was difficult to attract staff at the prevailing minimum wage. The dominant discourse on employment shifted as well, and it soon became bipartisan “common sense” that the problem haunting America was an eroding work ethic.

The system of entitlements that had been put in place over the preceding decades to protect vulnerable Americans, this thinking went, had backfired. An overly generous “welfare state” had created a coddled and indolent class of job-shirkers (Collins and Mayer 2010). In truth, even at its peak, the welfare system in the Unites States was less generous than that of other rich industrialized nations (Esping-Andersen 1990; Steensland 2007). Nonetheless, President Clinton, in 1996, signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, a piece of legislation intended to “end welfare as we know it” (Clinton 2006). It forced recipients of public assistance to sing for their proverbial suppers, no matter how menial the employment they acquired.

A seemingly permanent “crisis of work” is not unique to the United States. For some time now, Europe has been plagued by high unemployment and economic stagnation, a situation many attribute to inflexible labor markets. Burdensome state regulations and powerful labor unions, critics argue, have made it difficult for firms to hire and fire workers in response to fast-shifting business conditions.

Meanwhile, in China, decades of economic reform have liberalized the economy and produced staggering economic growth. In fact, in early 2011, China surpassed Japan to become the world’s second largest economy. Accompanying this rise in output, however, has been a surge in protests and strikes by workers in the country’s burgeoning factory system (Lee 2007). As they produce more and more goods for the world’s (and especially America’s) consumers, Chinese workers appear to be increasingly unsatisfied with their poor working conditions and lack of socio-economic mobility. Similar stories of labor discontent can be found in the world’s other emerging economies, such as Brazil, South Korea, South Africa, and India (Silver 2003).

The purpose of this book is to mobilize the conceptual tools of economic sociology to understand the place and fate of work under global capitalism. Economic sociology is ideally suited to this task. As an academic field it endeavors to put capitalism in world-historical perspective, as but one among many potential ways to organize economic activity. How, it asks, did private property and labor markets come to constitute the pillars of the modern global order? Why is the contemporary world converging upon an extreme version of capitalism (the free-market, or neoliberal, version most closely associated with the United States)? Is it folly to even imagine a post-capitalist future?

To address such questions, economic sociologists have assembled a range of theories, ideas, and methods. At the center of and unifying this assemblage is one key insight: that markets are social structures (Martin 2009). They come into being not as the expression of some natural law, but as strategic action projects that achieve success at particular historical moments (Fligstein and McAdam 2012; Hall and Soskice 2001). Markets of labor are no exception. To transform the basic human capacity to engage in meaningful work into a commodity requires persuasion, coercion, and ongoing intervention. To challenge the resulting fiction requires strategic action as well. As the paradigm of regulated capitalism (in which labor is afforded basic protections from the constant pressure of the market) gives way to unfettered market fundamentalism, it becomes ever more important to understand how these conflicts over labor’s status as a commodity play out.

Of Metaphors and Markets

People have a natural tendency to think metaphorically. When confronted with something new and puzzling, we make sense of it by comparing it to something that is already available in our vocabulary. It is thus not surprising that so many observers look at the crises of work that continue to plague us and attempt to make sense of them through organic or mechanical metaphors. That is, they compare the society under consideration to a sick person or a malfunctioning machine. If the unemployment rate in France suddenly spikes, we will surely hear a diagnosis of “Eurosclerosis.” If the United States’ inflation rate is too high, it could well be the case that the country’s “jobs machine” is “overheating.” And just as a physician prescribes a cure or a mechanic proposes a fix, the observer feels compelled to propose a line of action (typically a new policy or the modification of an existing one) that will bring the economy back to a healthy condition.

But what exactly would such a condition look like? How often, and for how long, do actually existing capitalist economies appear to exist in such a state? Let’s return to the example of the United States. Many have argued that it most closely approximates a pure, or, in the words of the sociologist Max Weber, “ideal type” capitalist economy. Among all the countries in the world today, that is, the United States most fully embraces the principles of private property and market exchange. Not only the United States’ continued leadership in the world economy, but the fact that so many countries have attempted to imitate its model of economic regulation over the past several decades, suggests that the US system of capitalism, despite its recent weaknesses, will continue to be a dominant paradigm for the foreseeable future. Nonetheless, even a cursory glance confirms that the US economy is notable precisely for its continual failure to meet its own standards of a “healthy” work system (Mishel et al., 2009).

Consider a handful of basic indicators, starting with an unemployment rate that recently peaked at 10 percent. Economists and policy-makers speak of a salubrious state of “full employment.” Somewhat counterintuitively, this does not mean a situation in which every single person who seeks a job will be able to find one, but rather one in which 95 percent of job-seekers can and do. In other words, an unemployment rate of 5 percent is acknowledged to be ideal for a well-functioning capitalist economy. However, if we look at the data for the past two decades (figure 1.1), we see that the actual unemployment rate hits this number only sporadically, on its way up or down. It’s as if a hospital patient’s temperature could not be maintained at a steady 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit, but swung back and forth between a bad fever and awful chills!

Data source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Figure 1.1 US unemployment rate, 1990–2011

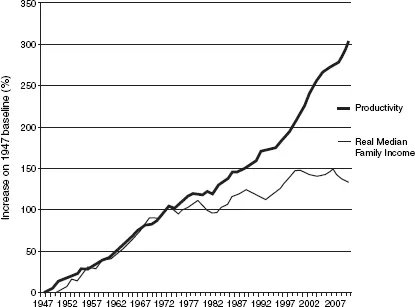

We can also consider the relationship between American workers’ productivity and their wages. Productivity refers to the amount of value that is produced by a worker in a given period of time and with a constant amount of inputs. According to some versions of economic theory (along with common principles of fairness), an increase in a worker’s productivity should be matched by an increase in that worker’s remuneration. This pattern certainly held for the early and middle parts of the twentieth century (see figure 1.2). However, for the past forty years – since approximately 1970 – the two figures have been decoupled: annual increases in worker productivity have not been rewarded with proportional increases in employee compensation (as inferred from trends in median family income). While American workers produce much more value today than they did twenty or thirty years ago, the size of their paychecks has budged barely at all. In fact, many have hypothesized that this discrepancy was one of the primary causes of the Great Recession that commenced in 2008: denied raises at work, American households turned en masse to credit card debt, reverse mortgages, and other unsound financial instruments to fund their consumption and maintain their standards of living (Reich 2010).

Data source: US Census Bureau and Economic Policy Institute.

Figure 1.2 Productivity growth versus real median family income growth in the United States since 1947

If capitalism is like a patient who is perpetually sick, how are we to explain its global dominance today? Perhaps an organic metaphor is not the optimal one after all. Let us consider instead the viewpoints of two early theorists of capitalism whose work remains central to the field of economic sociology: Karl Marx and Joseph Schumpeter.

Both of these thinkers eschewed metaphors depicting capitalism as an organism existing complacently in a state of harmonious equilibrium with its environment. Rather, they conceptualized capitalism as a dynamic, contentious, and continuously evolving social structure. For the nineteenth-century German philosopher Marx, this was a revolutionary system that generated immense wealth and unleashed powerful new methods of production. As a byproduct, however, capitalism generated repeated booms and busts, periods of economic expansion and contraction. Eventually, Marx argued, humanity would tire of weathering these repeated crises and, led by an alienated but mobilized working class, institute a post-capitalist, or communist, society characterized by collective ownership of the means of production, rational planning, and an equitable distribution of wealth.

Schumpeter, an Austrian economist of the early twentieth century, concurred with Marx’s assessment that capitalism possessed the unique ability to repeatedly revolutionize accepted ways of making and doing things. As the forces of supply and demand ran their course, they would select for those market actors most suited for survival. He labeled this process, in which existing businesses were eviscerated and new ones brought into being, one of creative destruction (Schumpeter 1994 [1942]). And though Schumpeter himself believed that capitalism could not survive these eternally recurring purges, other luminaries of economic thought (e.g., Friedman 2002 [1962]; Hayek 1996 [1948]) argued the converse: although the business cycle could be painful, especially for those industries and trades that became outmoded and were displaced, on the whole a system of private ownership and market competition was the only way that society could evolve and improve. The communist system that Marx proposed, in contrast, would ultimately stifle humanity’s entrepreneurial spirit.

In many ways, the story of the twentieth century was one of these contrasting visions. Following the Second World War, there arose a new global order centered upon a conflict between two economic systems: that of the United States – champion of free-market capitalism – and that of the Soviet Union—whose leaders embraced, at least in principle, the central tenets of Marxism. At no point did these conflicting visions erupt into direct military confrontation between the two sides. Rather, there played out a Cold War in which each nation sought to expand its political influence throughout key geographical areas and to exercise cultural hegemony in the emergent “world society.” In addition, and perhaps most importantly, the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in frantic contests to design innovative and efficient methods of production. The most high profile of these took place in the fields of aeronautics (the “space race”) and weaponry (the “arms race”). But across all sectors of their economies, the two nations implemented divergent methods of organizing work and workers: the one based on central planning and state ownership, the other on market forces and private property (Burawoy and Lukács 1985).

In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed and the Cold War ended. It is debatable the extent to which the Soviet Union’s demise was attributable to inherent failings in a socialist system of production. In some ways it was remarkable that Russia, a rural and feudal society on the eve of its 1917 revolution, was able to transform itself into a global industrial powerhouse over the course of the twentieth century. Regardless, the collapse of the Soviet Union signaled the triumph of Schumpterian-style capitalism. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, not only the former Soviet states but countries worldwide reformed their economic systems in line with the principle that the free market (and not central planning by state bureaucrats, traditional authorities, or an enlightened proletariat) should guide the production, distribution, and consumption of valued goods, services, and resources (Baccaro and Howell 2011).

In regard to the issue of work, the implications of this neoliberal revolution were clear. To increase productivity, maximize efficiency, and improve competitiveness, policy-makers must treat human labor like any other resource: that is, as a commodity to be bought and sold on the open market. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who, along with US President Ronald Reagan, spearheaded this neoliberal paradigm shift by launching attacks on labor unions and other institutions intended to protect workers from the vagaries of the market, famously stated the new common sense thus: from this day forward, “there is no alternative” to free-market capitalism (Harvey 2007).

But was this final chapter penned too soon? Even prior to the recession that hit in 2008, “crises of work” had not disappeared. If anything, they arose again and again, with what seemed like an ever-increasing frequency. In addition to the issues mentioned above (of unemployment, welfare reform, and stagnant wages), work remains implicated in a good many of the social problems confronting our world today: increasing inequality, illegal immigration, illicit discrimination, and on and on (Sassen 1998). In the words of economist Meghnad Desai (2004), it may be that we are witnessing “Marx’s revenge.” That is, despite the claims of free-market advocates, a system that treats human labor as a simple commodity is destined for instability. Nonetheless, with the dramatic end of Soviet socialism along with communist China’s continued drift toward a market system, there do seem to be few alternatives at hand.

Rather than a resurrection of Marx from the grave, it seems more likely that our era will remain one of “zombie economics” (Quiggin 2010) in which empirically discredited ideas – namely, absolute faith in the beneficence of free markets – continue to guide us. Now more than ever we need new concepts to dissect the social processes through which markets are produced and sustained in practice. This is especially true for markets in labor. It was capitalism’s greatest feat to transform the human capacity to work into a substance that can be bought and sold; while few other transformations have evoked such a backlash from society. To document how work is sustained as a “fictitious commodity” under capitalism constitutes the central task of what we propose to be a critical economic s...