![]()

Part One

The development of the dressmaking trade

![]()

1

‘About suppressing the women mantua-makers’

In March 1706 in Durham, Isobel Wood gave evidence before the tailors’ guild on behalf of her mantua-maker daughter, Elizabeth Browne. ‘Mantoes is a forreigne invencion,’ said Isobel, ‘and brought from beyond sea, and not used in England till about the year 167?’ – Isobel could not remember the precise date. She had been in service with Mr Hope, one of the Clerks of the Spicery to Charles II, and remembered ‘the Duchess of Mazarene, who came from beyond sea that yeare, and brought the garb of Mantoes with her’. Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin, came to England in 1675 after the death of her protector, the Duke of Savoy, and within a year she had become one of Charles II’s mistresses. Isobel remembered Mrs Hope ‘had her first Mantoe made by a Frenchman’.1 It seems likely, therefore, that Elizabeth Browne learnt about mantuas and how to make them from her mother.

It would appear the mantua was known in England before 1675, however. A portrait of Sir Robert Vyner, later Lord Mayor of London, with his wife, son and stepdaughter, shows Lady Vyner wearing a pale blue silk mantua over a decorated corset and a pink striped and brocaded petticoat.2 Lady Vyner died in 1674 so the portrait probably dates from 1673. It is a strange picture, in that while the two children are dressed in their silken best, the girl wearing lace and pearls, the little boy in a coat ornamented with gold braid and knots of yellow ribbon, their parents are in expensively casual undress. Sir Robert wears a banyan (a type of housecoat for men, often made, like Sir Robert’s, of a rich fabric) but sports a formal full-bottomed wig, while Lady Vyner wears pearls and sparkly earrings with her mantua and has had her hair elaborately coiffed. [Colour Plate I] The fashion spread rapidly. In the late 1670s, for example, Katherine Stewkley wrote from rural Cheshire to her cousin Penelope, in London: ‘Pray send me now word what is worn about the neck with a manto, I know they do not generally wear anything, but all people are not able to go bare-necked this winter.’3

Randle Holme mentions mantuas in The Academy of Armory printed in 1688: ‘There is a kind of loose Garment without, and Stiffe Bodies under them and was a great fashion for women about the year 1676. Some called them Mantuas.’ These early mantuas seem to have been something like a kaftan or dressing gown, a T-shaped garment, the sleeves cut in one with the bodice, shorter at the front than at the back and open at the front, worn over a skirt or ‘petticoat’. The garment wrapped around the body at the front and fastened with pins (if it fastened at all) and was often pleated and/or looped up at the back. The key thing about early mantuas, however, was that they were not fitted and would not have been difficult to make.

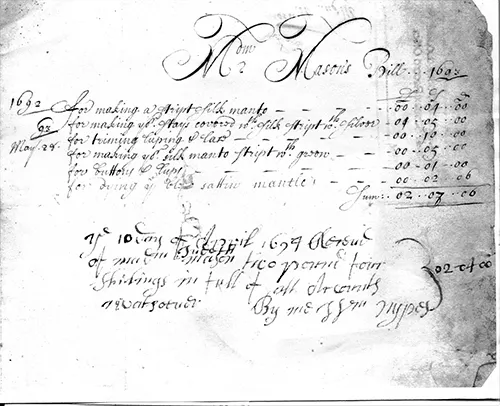

Corsets – Holme’s ‘stiffe bodies’ – were worn underneath giving the conical body-shape that was fashionable throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and where the corset was on show it was sometimes trimmed or covered to match the mantua. In 1692, for example ‘Madame Mason’ in Chichester (Sussex) acquired a mantua made of ‘strip’t silk’ for 4s.0d and a pair of stays covered in matching striped silk for £1.5s.0d.4 [Plate 1] In Berkshire, Lady Judith Alexander5 favoured black and silver as a colour scheme, and in 1691 she had a black ‘anterine’6 mantua made for 6s.0d., black petticoats trimmed with silver fringe (2s.6d) and a corset covered in black satin trimmed with silver (£1.17s.0d). A year later she had another similar outfit made.

Plate 1 Madame Mason’s bill, 1692–3.

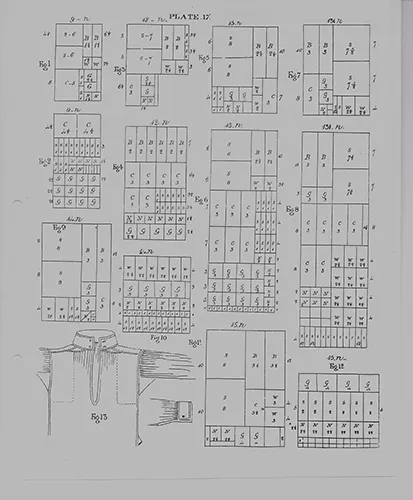

Up to the mid-1670s, those women’s garments that were not made at home had been made by tailors in the case of dresses, skirts, jackets and other ‘top’ garments, and by seamstresses in the case of shifts and underwear. Seamstresses worked in linen or cotton and they made men’s shirts, baby linen and women’s aprons as well as underclothes. The defining feature of seamstress-made garments was that they were composed of simple shapes, mostly squares and rectangles, gathered into a band where shaping was needed, but crucially, they were not fitted. The Workwoman’s Guide gives details of how to measure and cut the various pieces and recommends ways of cutting out numerous garments at the same time to optimize the use of fabric. The first edition of the Guide dates from 1838, but it codified techniques that had been in use for 200 years. [Plates 2 & 3] Being a seamstress was a recognized profession, seamstresses took apprentices and some of them seem to have made a good living. For example, in 1638 Elizabeth Collier of Minterne Magna in Dorset left £145.00, in 1648 Margareta Dennison of Deptford (London) left £132.00 and in 1650 Margaret Wilcox of Colyton in Devon left monetary bequests totalling £67.00.7 All three women also bequeathed considerable amounts of clothing and goods to be divided between family members. They were by no means unique, though there must have been many others who were much less successful.

Plate 2 Page from The Workwoman’s Guide, 1838, showing how to cut out a number of shirts at the same time to avoid wasting fabric.

Plate 3 Detail of a nineteenth-century chemise showing the use of an oblong for the sleeve and a folded square for the underarm gusset.

Tailoring, on the other hand, was a guild occupation; guild officials were powerful local figures who guarded the monopoly of their trade and its privileges jealously. By the seventeenth century few guilds admitted female apprentices, and the merchant tailors seem to have been particularly misogynistic.8 In 1679, for example, the Newcastle guild decreed that no woman could be taken on as an apprentice ‘by bond or indenture’.9 The employment of women was clearly a recurring problem in Oxford. In 1704 Michael Mercer was prosecuted for taking on Hannah Smith as an apprentice; on 11 May 1709 John White was fined 10s.0d for ‘setting Jane Hearne, spinster on work on his board contrary to the good ordinances and Byelaws of the company’; in January 1710 Andrew Bignell was fined for employing his maidservant ‘to work on his board’; a year later Richard Sherwood was in trouble for employing a journeywoman and in 1714 there were no fewer than three prosecutions of Oxford tailors who employed women.10

True, some tailors did involve their wives and daughters, and a tailor’s widow carrying on her late husband’s business could join the local guild, though seldom as a full member. However, few men were as bold about acknowledging the skills of their womenfolk as was John Porteous of Hawick in the Scottish Borders, whose widowed daughter worked as his journeyman and had learnt to cut out. In 1738 he set her to demonstrate her prowess before a representative of the local guild – and, despite the fact that he was a one-time deacon of that guild, the magistrates supported the guildsmen and he was sent to prison for it.11 Of course, not all tailors were guild members; those who set up in business in the country, or on the outskirts of towns where the guild’s writ did not run, were not subject to guild control, but nonetheless they too were almost always men who had served an apprenticeship during which they had been taught to cut and fit – skills which the seamstresses did not learn.

However, by the 1680s the supposedly traditional relationship between client and tailor was changing. More and more tailors were sub-contracting and selling goods ready-made, or keeping stocks of partially made garments that could be finished quickly to the customers’ requirements. By the late seventeenth century the London Merchant Taylors’ Company recognized ‘cutting tailors’ (who made garments from scratch) as a separate group.12 It became less and less easy for the guilds to oversee the trade and keep track of the various sub-contractors, and in many towns the power and authority of all the guilds were already beginning to decline.

Mantua-makers

The arrival of a new, easy-to-make fashion in the 1670s enabled enterprising women, like Isobel Wood’s daughter, to set themselves up as ‘mantua-makers’. We know some of their names but we do not know their backgrounds or how they had acquired their skills. It may be, as Norah Waugh surmised, that some seamstresses decided to expand their repertoires.13 Indeed, Randle Holme listed ‘A ROMAN DRESS, the mantua cut square behind and round before’ amongst the items made by ‘seamsters’. However, as Janet Arnold pointed out, the quality of stitching on early-eighteenth-century dresses is far inferior to that on most surviving examples of linen garments.14 It may also be that the wives and daughters of tailors decided to use skills they had learnt ‘helping out’ in the tailor’s workshop – in the 1690s, for example, Mause Robertson, wife of Robert Lindsey, an Edinburgh tailor, worked as a mantua-maker on her own account.15 Anne Buck also noted that many tailors’ wives in eighteenth-century Bedfordshire became mantua-makers.16

Unsurprisingly, tailors became concerned at the prospect of losing half their trade to female entrepreneurs. In France, a guild of seamstresses called the ‘Maîtresses Couturières’ was established in 1675, and they were permitted by law to make all women’s clothes except court dress and corsets.17 However, French tailors were unwilling to believe they no longer controlled the garment trade and they regularly visited couturières’ shops illegally and confiscated goods. As late as 1764 they seized a dress and petticoat that Madame Lahaye was delivering to a client; it resulted in a definitive court ruling that the tailors should allow the women ‘to exercise their trade in peace’.18 Merry Weisner has described how in Germany, restrictions on women working in the tailoring trades increased in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.19 The records of various English tailors’ guilds point to the resentment caused by the development of mantua-making as a separate trade. In 1685, for example, Priscilla Trattles was ‘presented’ to the magistrates in York, accused by the guildsmen of making women’s garments. In 1694, also in York, Widow Lodge was ‘discharged for exercising the Trade of a Draper or Taylor as she will answer the same by Law and for her neglect or refusal then she to be prosecuted against as the Law directs’. A case against Mary Yeomans ran from 1697 to 1699 and cost the York guild over £40.00 – including bribes to jurors and involving at least three indictments against Ms Yeomans.20

The guilds

One might have supposed that the London Merchant Taylors’ Company would have been at the forefront of opposition to the women making mantuas; after all, there were more mantua-makers in the capital than anywhere else and they were doing good business. However, by the end of the 1680s the Company was chiefly concerned with managing its property and its charities, particularly the schools and almshouses, and, if the minute books are to be believed, took little interest in the day-to-day affairs of its members.21 It was left to the provincial guilds to provide what opposition they could.

At the end of 1697 in Bristol, Mary Brobon was fined a pound for making mantuas. Whether the one prosecution was enough to deter others or whether the Bristol tailors decided it had been more trouble than it was worth is not apparent, but they did not record any other prosecutions. Similarly, the Salisbury tailors prosecuted Elizabeth Howlet in January 1699 for ‘unlawful working’ and fined her 40s.0d, but seem to have decided against pursuing cases against any other women.22

The Chester tailors had no such inhibitions. Between 1698 and 1725 they instituted at least forty-three investigations into women making women’s clothes, many of which came before the mayor. It was not a cheap exercise. Firstly the guild paid informers, next searchers had to be paid to investigate, then the constable had to have a fee for apprehending the woman concerned and bringing her before the mayor, transport costs had to be covered and often there was a further reimbursement for the constable and/or the searchers for ‘expenses’ incurred (usually in the local pub) while waiting to apprehend the woman. The cost varied between fourpence to despatch two ‘searchers’ to make enquiries, and the, admittedly exceptional, two pounds it cost to prosecute Mrs Williams in 1709. Some women were prosecuted several times – Susannah Young and ‘Oulton’s wife’ were regular offenders and they probably saw the occasional fine as a necessary business expense. However, what must have been particularly galling for the tailors was the number of offenders who, like Mrs Warmingham, another frequent offender, were the wives or relatives of members of the Chester guild.23

Enough was enough, and in October 1702 work began on a series of petitions to be sent to parliament – though it is not known whether the litiginous Chest...