eBook - ePub

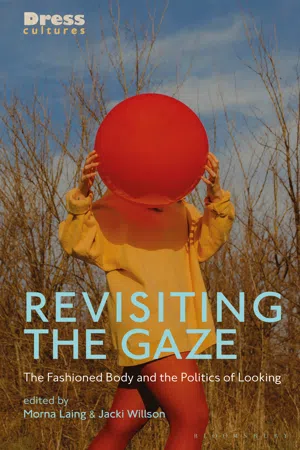

Revisiting the Gaze

The Fashioned Body and the Politics of Looking

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Revisiting the Gaze

The Fashioned Body and the Politics of Looking

About this book

In 1975 Laura Mulvey published her seminal essay on the male gaze, ushering in a new era in understanding the politics and theory of looking at the female body. Since then, feminist thinking has expanded upon and revised Mulvey's theory and much of the Western world has seen a resurgence in feminist activism as well as the rise of neoliberalism and shifts in digital culture and (self-)representation. For the first time, this book addresses what it means to look at the fashioned female body in this radical new landscape.

In chapters exploring the fashioned body within contexts such as queerness, veiling, blackness, pregnancy, fatness, and criminality, Revisiting the Gaze addresses intersectional debates in feminism and re-evaluates the concept of the gaze in light of recent social and political changes. With an interdisciplinary approach, bridging fashion and fine art, this book opens the door to discussions about the male gaze and the fashioned body.

In chapters exploring the fashioned body within contexts such as queerness, veiling, blackness, pregnancy, fatness, and criminality, Revisiting the Gaze addresses intersectional debates in feminism and re-evaluates the concept of the gaze in light of recent social and political changes. With an interdisciplinary approach, bridging fashion and fine art, this book opens the door to discussions about the male gaze and the fashioned body.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

‘Visual Pleasure at 40’

In 2015 Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ enjoyed its fortieth year.1 The essay first appeared in 1975 and since then has become the most cited and referenced article in the history of Screen journal and seminal to debates on feminism and spectatorship.2 To mark the essay’s fortieth year the BFI hosted an event where Mulvey spoke alongside scholars and film-makers who shared their thoughts on the significance of the essay, in both personal and scholarly terms.3 In her contribution to the panel, Mulvey emphasized that the essay was very much a ‘historical document of its time’ for

it could only have been written within a narrow window of a couple of years: after the influence of the Women’s Liberation Movement changed my relationship to Hollywood cinema, but before film studies came into existence, necessarily ruling out such sweeping statements and manifesto-like style of writing.4

Mulvey’s writing was polemical, politicized, but that was her intention. For, as art historian Tamar Garb observed, the essay was about ‘[moving] away from the pervasive idea that looking was disinterested’, in the Kantian sense, instead conceptualizing spectatorship as part and parcel of gender politics and other hierarchies of power.5

The ‘male gaze’ was mentioned just once in Mulvey’s essay, and since its appearance in 1975 it has ‘[floated free] and become something of its own’, to quote Mulvey herself.6 The term has been mobilized by students and scholars alike, becoming central to debates on gender and the politics of looking, extending far beyond the ambit of Film Studies alone. Yet, in the process it has sometimes been detached from its psychoanalytic underpinnings, with the complexities of Mulvey’s argument reductively paraphrased at times. The essay has been critiqued for its privileging of gender over other axes of identity, which are also imbricated in spectatorship, such as same-sex desire and the politics of race.7 This speaks to critiques of Second-Wave feminism, more generally, for its failure to register the power differentials between women of different social groups and the subsequent emphasis on intersectionality in feminism since the 1980s. Finally, Mulvey herself has acknowledged that aspects of the essay have ‘necessarily been rendered archaic by changes in technology’8 and has revisited and revised it in her subsequent writing, such as Death 24x a Second (2006).9

Mention of appearance, styling and erotic spectacle in ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ foretold how fruitful the gaze would become for making sense of the fashioned female body. Yet, in the period since the essay was published we have witnessed the evolution of Western capitalism into its current neoliberal formulation, with consumer culture absorbing the more palatable aspects of feminism in order to sell it back to women as a commodity.10 Furthermore, with the recent resurgence of feminist activism – being termed ‘Fourth Wave’11 or ‘digital’ feminism12 – debates on fashion and the gaze have evolved enormously. Blogs such as Man Repeller playfully mock the idea of the ‘male gaze’13 while women have explored the empowering potential of self-authored images of the female body. Activists on the street have used their own fashioned bodies as a site for articulating protest, through movements such as FEMEN and SlutWalk, with these protests, in turn, being critiqued on social media for their privileging of white, heteronormative, cis-gendered bodies.14 Thus, what is new about feminist activism in the twenty-first century is the way protest on the street has converged with hashtag feminism on social media platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

These social and digital changes provided the impetus for a re-examination of the fashioned female body and the politics of looking. This edited collection brings together a selection of papers that were presented at Revisiting the Gaze: Feminism, Fashion and the Female Body, a conference we organized in June 2017 at Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts London. Working from the premise that the gaze is intersectional,15 we wanted to consider what remained fruitful in Mulvey’s essay as well as thinking through new ways of theorizing fashion, the female body and spectatorship. Part of this involved addressing the relative invisibility of certain bodies – such as the ageing female body – and the hypervisibility of other bodies, such as the Muslim body or the fat body. This approach feeds into the present volume, which represents a timely contribution to scholarship on looking – in both popular and fine art contexts – with the fashioned female body being the motif connecting these two fields of visual culture. Revisiting the Gaze provides a fresh perspective on spectatorship in the light of digital feminism or so-called ‘Fourth Wave’ feminism, offering up new intersectional approaches to performative cultures where fashion, pleasure and identity interweave. That being said, we would like to acknowledge at this point the limitations of the volume. It does not include, for instance, essays on the trans body, the disabled body or the ageing body, although we invited, and endeavoured to include, as many perspectives as possible.

This introductory chapter sets the scene for the essays that follow: firstly, by mapping the ways in which scholarship on the gaze has evolved since 1975, and secondly, by turning to consider intersectional identities and the politics of looking at the fashioned female body in the digital age.

The evolution of the gaze

In the following, oft-quoted passage, Mulvey introduces the concept of the ‘male gaze’:

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Woman displayed as sexual object is the leit-motif of erotic spectacle: from pin-ups to strip-tease, from Ziegfeld to Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire.16

Mulvey develops her argument by building on the work of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan as well as her own textual analysis of Hollywood narrative cinema. This approach, rooted in semiotics and psychoanalysis, can therefore be distinguished from that of John Berger, who studied spectatorship and the female body from a Marxist perspective in Ways of Seeing, published several years earlier, in 1972.17 The tension between the body in representation and the body as theorized by Lacan is something addressed by Rosa Nogués in this volume. Her essay ‘Killer Looks’ explores a series of portraits by the artist Marlene McCarty, which depict young women convicted of matricide. While Mulvey looked to Lacan’s discussion of the Mirror Stage to theorize the constitution of the ego, Nogués turns to Lacan’s notion of Other jouissance in order to problematize the very concept of sex itself. Psychoanalytic approaches are less common in the field of Fashion Studies,18 and it is therefore fruitful to see Nogués put her essay in dialogue with the work of Alison Bancroft, who theorized the female body from a Lacanian perspective in Fashion and Psychoanalysis (2012).19

Mulvey has reformulated her theory on spectatorship at several points in her career, opening up, at least theoretically, the range of viewing positions available to women and men. She did so explicitly in her 1981 essay, ‘Afterthoughts on “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” Inspired by “Duel in the Sun” (King Vidor, 1946)’.20 According to Mulvey, this second essay was prompted by ‘the persistent question “what about the women in the audience?”’21 Recognizing her own enjoyment in viewing Hollywood melodramas, Mulvey concluded that ‘however ironically it had been intended originally, the male third person closed off avenues of inquiry that should be followed up’.22 In ‘Afterthoughts’, Mulvey argued that female spectatorship involved an ‘internal oscillation of desire’ that ‘lies dormant’ until activated by the narrative and visual pleasures offered up in Hollywood cinema.23 By this account, the female spectator shifts between identification with a masculine position (such as the ‘active’ male protagonist) and identification with a feminine position (masochistic identification with an objectified female character). The masculine position here represents a kind of temporary nostalgia for the pre-Oedipal phase of active sexuality, which is later repressed upon entrance into ‘passive’ adult femininity. The metaphor of transvestitism is thus invoked to characterize the unstable nature of this viewing position: ‘for women (from childhood onwards) trans-sex identification is a habit that very easily becomes second Nature. However, this Nature does not sit easily and shifts restless in its borrowed transvestite clothes’.24

Mulvey would later reformulate the idea of ‘active’ female spectatorship through the concept of curiosity, which allowed for ‘greater complexity’ than the arguments presented in the earlier phase of her work.25 The ‘aesthetics of curiosity’, and particularly the myth of Pandora, allowed for the possibility of an ‘active, investigative look, but one that was this time associated with the feminine’.26 In turn, this offered ‘a way out of the rather too neat binary opposition between the spectator’s gaze, constructed as active and voyeuristic, implicitly coded as masculine, and the female image on the screen, passive and exhibitionist’.27 Curiosity, Mulvey argued, is experienced as something akin to a drive, which involves ‘a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- Notes on the editors

- Notes on the contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction Morna Laing and Jacki Willson

- Part I: Looking: The optic and the haptic

- Part II: Looking through neoliberalism

- Part III: Looking at the ‘other’

- Index

- Imprint

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Revisiting the Gaze by Morna Laing, Jacki Willson, Morna Laing,Jacki Willson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Design della moda. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.