- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Empire

About this book

The 19th century was a time of new sensory experiences and modes of perception. The raucous mechanical intensity of the train and the factory vied for attention with the dazzling splendour of department stores and world fairs. Colonization and trade carried European sensations and sensibilities to the world and, in turn, flooded the West with exotic sights and savours. Urban stench became a matter of urgent public concern. Photography created a compelling alternate reality accessible only to the eye. At the turn of the 20th century, the telephone and the radio isolated and extended the sense of hearing and electrical networks spread their webs throughout cities. These novel experiences were reflected in contemporary art and literature, which strove for new ways to express modern sensibilities. A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Empire brings together a group of eminent historians to explore the aesthetic, cultural and political formation of the senses during a period of momentous change.

A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Empire presents essays on the following topics: the social life of the senses; urban sensations; the senses in the marketplace; the senses in religion; the senses in philosophy and science; medicine and the senses; the senses in literature; art and the senses; and sensory media.

A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Empire presents essays on the following topics: the social life of the senses; urban sensations; the senses in the marketplace; the senses in religion; the senses in philosophy and science; medicine and the senses; the senses in literature; art and the senses; and sensory media.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Empire by Constance Classen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire sociale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

_____________________________________

The senses are essential to sociability. They help connect us to others, and allow us to participate in communities. At the same time, it is through our senses that communities, in the forms of crowded streets and buildings, and communal activities, can seem to overwhelm us, and challenge our autonomy and individuality in uncomfortable ways. Yet the social life of the senses is not just to be understood in relation to connectivity outside of the self. As nineteenth-century research in physiology and psychology demonstrated and explained, the senses worked actively, in combination with one another, within the individual body—creating, indeed, an important component of what constituted individuality itself.

This chapter explores the concept of the “social life” of the senses in three distinct ways. It considers how the senses connected individuals to the environment that surrounded them. The busy thoroughfares of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century cities continually stimulated the eye, nose and ear, refusing sensory rest to the perceiver, and making them acutely aware that their own lives were always related to the physical existence of others. Sound and smell have the power to travel into—and out of—dwellings and workplaces, eroding the barrier between domestic and public existence. Appealing to the sensory imagination was a powerful tool at the disposal of social commentators. Information received through the senses, moreover, led people to make, both consciously and unconsciously, discriminations and judgments about class, ethnic identity, background, and gender—the tools through which one apprehends what Raymond Williams termed a “knowable community” (Williams 1975: 165), and through which one tries to make sense of what has become the more familiar phenomenon of the crowded, chaotic, contradictory modern world.

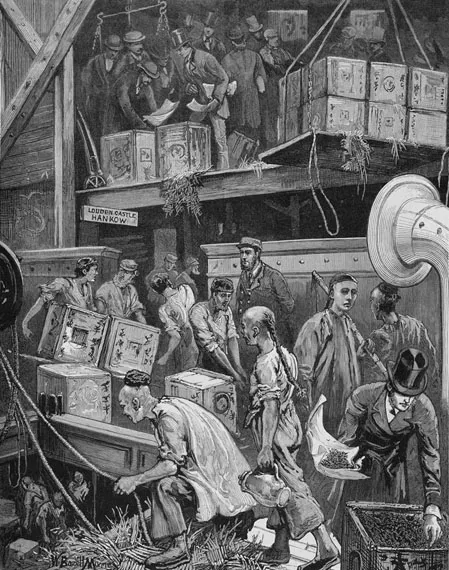

The senses work also to connect people to wider, unseen communities than those in which one lives—communities composed of networks of production, distribution, and consumption. Merely to hold a book, for example, or to finger the fabric for a new dress, or to drink a cup of tea with sugar is to touch or taste something that has been made and transported by other hands, and in other places—sometimes very far-away places indeed. Whilst this contact must frequently have been nonconscious, the physical imprint left by human labor was something that was deliberately recalled by those—like John Ruskin, like those who participated in the Arts and Crafts movement—who repudiated the impersonality of mechanization and the suppression of individuality that mass manufacture brought with it. To draw attention to the engagement of senses in creating, wearing, or eating something is a way of drawing connections between people; to show how the senses may participate in broad and invisible networks.

The senses connect us not just to our present, but to our pasts. Starting from Marx’s insight in his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 that they are not merely used as organs through which to respond to the present moment, but that they are a potent source of material memories, Susan Stewart has reminded us that “such memories are material in the sense that the body carries them somatically—that is, they are registered in our consciousness, or in the case of repression, the unconscious knowledge, of our physical experiences” (Stewart 1999: 17). If mid-nineteenth-century physiologists and their popularizers would attribute this to the workings of the “nervous system,” with the “great sympathetic nerve” running down the spine, branching out into other organs, and connecting in the brain, and if modern neuroscientists explain this through the establishment of neural pathways that create habits and associations, the overall concept is the same: that sensory impressions, stored in the body, work together to establish our individual conceptualization of who we are.

Finally, this chapter will consider how the senses may be said to have a busy social life of their own within any individual who is the agent of perception. G. H. Lewes, in The Physiology of Common Life wrote (anticipating William James) of the “vast and powerful stream of sensation belonging to none of the special Senses, but to the System as a whole” that constitutes an individual’s experience of life (Lewes [1859] 1860: 49). As he points out, we may be pretty much unconscious of all the demands that are being made on our sensory apparatus at any one time:

While I am writing these lines the trees are rustling in the summer wind, the birds are twittering among the leaves, and the muffled sounds of carriages rolling over the Dresden streets reach my ear; but because the mind is occupied with trains of thought these sounds are not perceived, until one of them becomes importunate, or my relaxed attention turns towards them.

Lewes [1859] 1860: 40

As we will see throughout this chapter, the obtrusiveness of some aspect of the external world onto an individual’s consciousness is one of the means by which one can be made uncomfortably aware of one’s embodied existence within it. But what is important to my purpose here is that Lewes was one of a number of influential thinkers whose research on the nature of perception emphasized the mutual imbrication of the senses in a person’s physiological and psychological make-up. Recognizing the importance of sensory collaboration is certainly nothing new, but a cluster of notable thinkers in the Victorian period repeatedly returned to the topic of how, precisely, the senses work in cohort with one another to produce our understanding of the world and ourselves. In what lies ahead, I will be drawing on some of these theorists, whose work bridged physiological research with the developing discipline of psychoanalysis. But I will also be making extensive use of literary texts, for the way in which a writer brings together the workings of the different senses, using language that stimulates the sensory memories and associations that we carry within our own bodies, may be said to constitute a further form of social life: one that is constituted by the imagination of the individual reader, and yet that inescapably links them to other consumers of the same text.

Commentators on the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century city, whether writing fiction or poetry, or trying to draw as accurate a description as possible in journalism, reports, or travelogues, endlessly commented on the visual plenitude, the mingling of odors pleasant and foul—more often than not, foul—and the constant clanging, shouting, rattling, barrel-organ-churning sounds of the streets. Artists and photographers, limited to appealing to their audience’s visual imagination in the first instance, helped chronicle this chaos. Consider, say, Phoebus Levin’s 1864 painting Covent Garden Market (see Figure 1.2). Although the composition and lighting directs the eye to focus on certain groups—the bargaining taking place just left of center, the porter with a huge basket of produce on his head on the right of the picture—the fact that there is no unifying perspective or clear sight lines mimics, through our viewing practice, the experience of having our attention pulled first in one way, then another, as if we had actually been present. There is plenty of motion, which stops us regarding it in a contemplative way—unless we focus on the deliberately obscured group of ragged girls on the left-hand side, looking for dropped or discarded fruit or vegetables, and representing those who are more figuratively obscured in society, even as the more respectable woman in front of them, apparently buying a bunch of flowers, appears to be the object of the speculative gaze of the lounging group of men to our right. However, the painting is, necessarily, silent. It invites the spectator to supply the sounds that Charles Dickens wrote of in his essay on Covent Garden Market in Sketches by Boz: “The pavement is already strewed with decayed cabbage-leaves, broken hay-bands, and all the indescribable litter of a vegetable market; men are shouting, carts backing, horses neighing, boys fighting, basket-women talking, piemen expatiating on the excellence of their pastry, and donkeys braying” (Dickens [1836] 1995: 53). We have, moreover, to add in the smells: the overwhelming perfume of flowers remarked on by many visitors on the one hand, and the stench of rotting fruit and vegetables—not to mention horse and donkey manure—on the other.

At least by the time Levin painted his picture, one of London’s most notorious stenches, that produced by the sewer known as the Thames (together with the composite effect of other bad or absent drainage), had significantly improved due to the work of the Metropolitan Board of Works. In the first half of the nineteenth century, even in the most fashionable districts, there were, as Henry Mayhew remarked, citing an 1849 report, “many faulty places in the sewers which abound in noxious matter, in many instances stopping up the house drains and smelling horribly” (Mayhew ([1851] 1851–61, II: 395). Friedrich Engels, visiting England between November 1844 and August 1846, was struck not just by the foul stench that emanated from slops thrown into the street—and, indeed, by the smells of London street markets—but by the “most revolting and injurious gases” emanating from inadequately buried corpses in the pauper burial ground (Engels [1845] 2009: 296). There was a frequent and sickening smell of coal gas as well, especially when the gas mains leaked; leather tanning in Bermondsey was notoriously odiferous (it used dog excrement in its process), and many other small industries emitted fumes and smoke of various kinds. Nor was this olfactory unpleasantness confined to London: it was endemic to all large cities. In Manhattan, sewage and refuse was dumped straight into the rivers, and washed back again. “In summer, at low tide,” wrote the Health Officer of the Port in 1865–6, “this filth lies frothing like yeast, setting free … offensive and pernicious gases and insupportable odors … which every breeze … spreads over the island” (New York Chamber of Commerce Annual Report 1865–6, quoted in Scobey 2002: 136).

Smells were not alone in providing an offensive assault on the human body. As John Picker tells us in Victorian Soundscapes, during the mid century, “street sounds also came to be represented as threatening pollutants with noxious effects” (Picker 2003: 66), quoting a letter cited in Michael T. Bass’s Street Music in the Metropolis—one of many similar pieces of correspondence—that complained of this nuisance that it is “quite as destructive to health, comfort, and quiet, as bad smells, bad drainage, and the proximity of disorderly houses” (Bass 1864: 88). Other letters specified some of the problems: mock Scotsmen dancing to bagpipes; “Italian organ-grinders, blind men with screeching clarionets, boys with droning hurdy-gurdies” (Bass 1864: 59). One can add the cries of street hawkers, or the clatter of carriages, or, for those situated near railway tracks, the “shrieking, roaring, rattling” trains that Dickens, in Dombey and Son, represents as whirling along with the triumphant speed of death (Dickens [1848] 2002: 312).

Later, there were the sounds of the internal combustion engine—not just cars, but buses. The Motor-Car Journal reported in July 1908 that in the previous year, 4,362 of London’s 8,507 buses had been reported as “unfit for traffic on account of noise” (“Motor Traffic in London” 1908: 435)—noise amplified in narrow streets. In Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, the narrator records the general “bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; … the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead” (Woolf [1925] 2005: 4)—a set of sounds which, representing the inherent life of the bustling city, Clarissa Dalloway finds enlivening, almost comforting—is sliced into by the sound of a car backfiring, mistakable for “a pistol shot” (13). This sound is a structural device, joining people together synchronically in their private responses, creating social cohesion through response to an urban sound even though in sociable terms they are strangers to one another. It also links them diachronically. The First World War had left its sensory imprint on people’s nervous systems, and the extraordinary demands that it made on the senses—especially, in this novel, that of the shell-shocked Septimus Warren-Smith—is something to which I’ll return.

Sensory appeals bind people together in a positive as well as in a negative way: in the sights and sounds and smell of the music hall or opera or theater or circus; in the durbars and pageants of empire—as Tim Barringer, for example, has demonstrated in his analysis of the role that the aural (especially Elgar’s music) played in the staging of the 1911 Delhi Durbar, and in its theatrical representation in London the following year (Barringer 2006). Without discounting for a moment the maddening effects of the cacophony created by street musicians—one that stimulated a crescendo of rhetorical protest that culminated in the passing, in 1864, of the less than effective Street Music Act—the thing that stands out in these protests is the way in which they are colored by class anxiety and xenophobia, and by a fear that the privacy of the home (both as a domestic sanctum and as a working space) was being violated by the heterogeneity of the streets outside.

Banding together in a campaign to try and suppress noisy street supporters was one obvious way in which an identifiable social grouping could be formed through a shared reaction to an acoustic environment, but other virtual communities, operating through shared assumptions rather than in any programmatic sense, reacted to the world around them through what were, in effect, class codings, or responses rooted in other ideological biases. Janice Carlisle, in Common Scents, has shown how novelists of the 1860s played on their audience’s pre-existent associations with what one popular commentator of the time called “ambassadors from the material world” (Wilson 1856: 18). Drawing, for example, on psychologist Alexander Bain’s discussion of smell in The Senses and the Intellect (1855), she demonstrates how odors associated with labor—with mills and warehouses or beer brewing or a pastrycook’s kitchen—were deemed especially offensive (Carlisle 2004: 42). To evoke sensitivity to certain smells—as does Esther Lyon’s father, in George Eliot’s Felix Holt, when he explains the necessity of the wax candle that’s burning by saying that his daughter “is so delicately framed that the smell of tallow is loathsome to her” (Eliot [1866] 1995: 60)—is a concise way of telling an audience about social position and ambition. Other social segments may be quietly damned through their alleged olfactory preferences, as when the increasingly environmentally aware John Ruskin sneered at the “sporting people who have learned to like the smell of gunpowder, sulphur, and gas-tar [the latter two were used to drive rabbits from their warrens] better than that of violets and thyme” (Ruskin [1872] 1903–12: 436).

For Ruskin, the appeal of the natural world to the senses was necessary and restorative, and perhaps more than any other nineteenth-century writer, he repeatedly urged, and practiced, habits of visual attention. But the natural world could itself be overwhelming in its assault on the senses, even though the demands made by rural scenes might be far less toxic in their oppressiveness than those of the city. In Chapter 19 of Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy evokes a typical June summer evening, “the atmosphere being in such delicate equilibrium and so transmissive that inanimate objects seemed endowed with two or three senses, if not five”—a strange statement, that appears to make the objects themselves receptive, rather than acting as the source of stimuli for the human observer. Tess finds herself on the uncultivated edges of the farm garden, which “was now damp and rank with juicy grass which sent up mists of pollen at a touch; and with tall blooming weeds emitting offensive smells—weeds whose red and yello...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Preface

- Editor’s Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Transformation of Perception

- 1 The Social Life of the Senses: The Assaults and Seductions of Modernity

- 2 Urban Sensations: The Shifting Sensescape of the City

- 3 The Senses in the Marketplace: Stimulation and Distraction, Gratification and Control

- 4 The Senses in Religion: Migrations of Sacred and Sensory Values

- 5 The Senses in Philosophy and Science: From the Senses to Sensations

- 6 The Senses in Medicine: Seeing, Hearing, and Smelling Disease

- 7 The Senses in Literature: Industry and Empire

- 8 Art and the Senses: From the Romantics to the Futurists

- 9 Sensory Media: The World Without and the World Within

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Copyright