![]()

ONE

Techniques, Materials, Skill

hile the ensuing chapters will investigate a range of Holbein’s paintings, examining their content and style in relation to their historical and cultural context, we will begin by concentrating on his graphic techniques, which show great versatility at employing varying materials and methods of application. Holbein’s drawings served a range of purposes: to capture visual ideas quickly, to render specific details of people and objects as potential models for paintings, and as designs for artworks to be executed by other craftsmen in glass, metalwork or other materials. Only a small proportion of Holbein’s drawings survive and the great majority are highly finished preparatory works, which during his lifetime probably served as templates that could potentially be reused. Only a handful of sketchier drawings hint at what must have originally been the largest proportion of his drawn images, quick sketches and the varied stages of preliminary work leading up to more finished drawings. Nevertheless, by comparing the materials of Holbein’s extant works with those of his father, and by dating as precisely as possible his earliest uses of new materials, we can deduce which techniques he must have learned growing up in his father’s workshop, as opposed to those that he took up

at a later date, and from there assess why he might have found new techniques advantageous.

We know almost nothing about Holbein’s upbringing in Augsburg, although three direct sources situate him as a child together with his older brother, Ambrosius, in their father’s workshop: the portraits made by the elder Holbein in a painting of 1504 and a drawing of 1511 (see illus. 32 and 2), plus an inscription of their names in diminutive form (‘Hensly’ and ‘Brosi’) on the back of an undated workshop drawing now at University College London.1 Everything else is speculation, since no surviving independent works can be attributed to Holbein the Younger from this period (that is, any drawings or the like from his training), nor are there any other documentary records about him before he arrived in Basel by the end of 1515. He might well have contributed as an apprentice to some of his father’s works, although his hand cannot be securely identified. However, we can guess that he might have found Augsburg a stimulating environment: it was a large and dynamic city, a major centre of political, economic and cultural activity.2 On a few occasions (including in 1500, when Holbein was still a toddler) Augsburg hosted meetings of the Imperial Diet, the peripatetic legislative body of the Holy Roman Empire. As an Imperial Free City, it benefited from civic self-governance with no immediate ruler other than the Holy Roman Emperor himself, in those years Maximilian I, who frequently visited Augsburg and was sketched riding on horseback by Holbein the Elder at some point in the early 1510s.3 Augsburg was the centre of the Fugger banking network and a hub in European trade, particularly textiles. With a vibrant commercial market that readily imported new ideas and products, the city fostered innovations in book publishing and print-making. For all of these reasons, many important people lived in Augsburg and many more passed through it.

Hans Holbein the Elder, born around 1465, had settled in Augsburg by 1494, although he made artworks for clients across southern Germany and as far north as Frankfurt.4 He painted individual portraits (illus. 4) and designed objects in other media such as metalwork, prints and stained glass, although he is best known for his religious paintings, from small devotional panels (see illus. 33) to epitaphs, votive pictures (see illus. 32) and altarpiece wings. A key point to emphasize here is that the large size of many of these artworks required workshop assistants and collaboration, so that young Hans during his childhood would have encountered a range of artists who worked in different media, and seen how large-scale art-making was a highly collaborative process. For instance, the elder Holbein’s younger brother Sigmund (see illus. 5) and the painter Leonhard Beck worked as his assistants from 1497 until at least 1501.5 A coordinated group of panels made for the nuns of Augsburg’s Dominican convent of St Katherine (illus. 32) were painted by Holbein the Elder, Hans Burgkmair the Elder and another painter known only by the initials L. F., and whether these painters worked in direct collaboration or not, they must at least have studied each other’s panels to ensure sufficient coherence across the series (as well as emphasizing their individual innovations). Holbein the Elder’s large painted altarpiece wings completed in 1502 for the Cistercian monastery in Kaisheim, about 50 kilometres (30 mi.) north of Augsburg, opened to reveal a sculpted central subject by Gregor Erhart, within a casing made by the joiner Adolf Daucher; a few years later the same group, plus the gilder Ulrich Apt, worked on another large altarpiece for the Augsburg collegiate church of St Moritz.6 Holbein the Elder’s final payment for this work in March 1509 included five gulden for his wife and one for his son, most likely Ambrosius, who would have been about fifteen years old at the time and thus old enough to have started working as an apprentice.

4 Hans Holbein the Elder, Philipp Adler, 1513, oil on wood (limewood?).

It is striking that the younger Holbein never specialized in large-scale cross-media works as his father did. Although Holbein must have had some assistants at points in his career, and some high-quality copies of his drawings indicate that other artists were in a position to study his artworks closely,7 the great majority of his extant images are small enough, and few enough in number, to have been carried out individually. But Holbein probably learned through his early training how to adapt his drawings for different kinds of practitioners, particularly how drawings made as designs for artists working in different media might employ specific techniques and materials chosen to suit their purpose. He probably began learning such techniques directly from his father, who likewise made at least a few drawings as designs for other media,8 though the changes in the younger Holbein’s materials and styles across the years imply that direct experience led him to adjust these techniques.

No documentation confirms the elder Holbein’s training of his sons, but technically and conceptually their earliest work shows close affiliation with his. Moreover, it seems natural to infer from the two sets of early portraits the father’s pride in (and affection for) his sons. In 1504, when the boys were about ages five and eight, the elder Holbein inserted a self-portrait together with the two of them as witnesses to the baptism of St Paul in the lower left scene of one of the paintings made for the Dominican convent’s panel cycle (see illus. 32). Each painting in the series was paid for by one of the wealthy nuns, so the financier of this panel, the prioress Veronica Welser, must have approved the artist’s intrusion into the scene.9 Strikingly, the attention among the small family group focuses on young Hans on the left: the father rests one hand on the boy’s head and appears to point to him, rather than across to St Paul, while gazing out at the painting’s viewers. Older brother Ambrosius protectively embraces his younger sibling, while little Hans gazes at the baptism scene with one hand on his chest and a stick of some kind (a youthful pilgrimage staff?) in his dominant left hand. The composition encourages speculation. Had the boy recently survived a life-threatening illness? Were his precocious artistic talents already in evidence? The absence of the boys’ mother, presumably still alive when this painting was completed in 1504, unless the wife documented in 1509 was a later remarriage, suggests a focus here on male professional identity. The elder Holbein may have already recognized that both boys, especially the younger one, had inherited the talent to eventually follow in his footsteps as successful artists. It is possible that knowledge of the boys’ later careers encourages mis- or over-reading of the portraits’ significance here, although surely the insertion of these figures into a professional commission implies a strong sense of familial identity on the part of the elder Holbein.

Holbein the Elder recorded his sons seven years later (see illus. 2) in a metalpoint drawing dated 1511 at the top and listing the ages of the boys as fourteen for ‘Hanns’ at the right and perhaps seventeen – the number is damaged – for ‘prosy’ at left.10 (This inscription, together with a self-portrait at the end of Holbein the Younger’s life giving his age as 45 and the year 1543, leads to the conclusion that he was born in late 1497 or early 1498.) Some of the lines of Hans’s features are strengthened with black ink (the slightly darker lines seen at his lips, nose and eyes) and the numbers ‘99’ and ‘100’ at the bottom are later additions, but the main technique is metalpoint, where a stylus (usually predominantly of silver or copper) leaves a line through friction with the paper or vellum surface that has been pre-treated with a coating of bone ash or chalk.11 The father focused on each boy’s face and used a combination of outline and modelling strokes to highlight the parallels as well as differences in their physiognomies and hairstyles. The inscription of their names, joined at the centre to ‘Holbain’, emphasizes his interest in recording vivid likenesses of members of his immediate family.

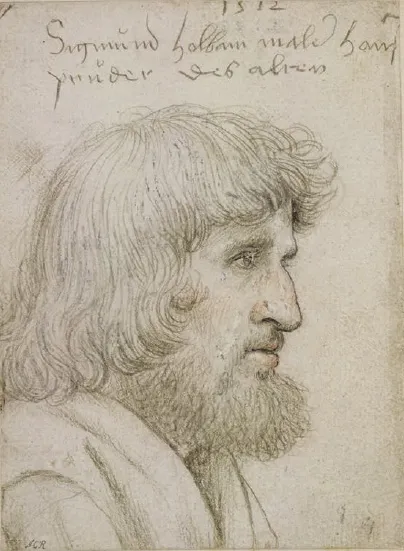

5 Hans Holbein the Elder, Sigmund Holbein, 1512, silverpoint with black and red chalk, heightened with white bodycolour, on white prepared paper.

Metalpoint was the elder Holbein’s favoured technique for taking sketches of people (and occasionally objects) from real life. Several of his extant drawings of individuals are identified by inscriptions, while others are anonymous, evidently taken out of personal interest or as potential models to insert within depictions of crowd scenes. Although metal-point was a demanding technique, insofar as lines could not easily be erased once made, the prepared materials were quick to use, non-messy and easily transportable. Artists of this era therefore often carried metalpoint-prepared paper bound in small notebooks to take sketches while travelling, as Albrecht Dürer did when he visited the Netherlands in 1520–21 (in addition to making drawings in other media).12 In his 1512 drawing of Sigmund Holbein, identified as the artist’s brother in the inscription at the top, Holbein the Elder expertly varied the density and quality of lines to create an impression of the varying textures of Sigmund’s hair and beard, with the light on the top of his head contrasting with the shading of the ends of his curls (illus. 5).13 The edges of the features are reinforced by precise ink lines, and further added touches of red chalk on the lips and cheek enhance the contrast of skin against the light background.

6 Hans Holbein the Younger, Jacob Meyer and Dorothea Kannengiesser, 1516, diptych, oil on limewood.

Holbein the Younger’s earliest extant portrait drawings likewise employ metalpoint enhanced with red chalk (illus. 7).14 Soon after moving to Basel, the eighteen-year-old Holbein painted a portrait diptych of the mayor of the city, Jacob Meyer zum Hasen, with his wife Dorothea Kannengiesser (illus. 6), signed with the initials ‘H H’ and dated 1516 in the cartouche above Jacob’s head. The overall aesthetic of the composition is broadly reminiscent of some of Holbein the Elder’s portraits, like the 1513 rendition of the prosperous merchant Philipp Adler (illus. 4), which sets the sitter against an abstract blue background framed by a classically profiled architrave and frieze supported by pilasters. Holbein the Younger’s portrait similarly features a blank blue background and a classical archway, here spread across the two panels of the diptych, but he took inspiration from a portrait woodcut by Hans Burgkmair the Elder to set the archway at an angle, creating a more dynamic arrangement (it would also have been difficult to ...