- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

United Nations Development Programme and System (UNDP)

About this book

This volume provides a short and accessible introduction to the organization that serves as the primary coordinator of the work of the UN system throughout the developing world –the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The book:

- traces the origins and evolution of UNDP, outlining how a central UN funding mechanism and field network developed into a more comprehensive development agency

- evaluates the UNDP's performance and results, both in its role as system coordinator and as a development organization in its own right

- considers the return of the UNDP to a more central role within the UN development system, in order to review the successive attempts at UN development system reform, the reasons for failure and the future possibilities for a more effective system with the UNDP at the centre.

Offering a clear, comprehensive overview and analysis of the organization, this work will be of great interest to students and scholars of development studies, international organizations and international relations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The origins of UNDP

• The origins of UN technical assistance

• The Expanded Programme of Technical Assistance

• The Special Fund

• OPEX and the principles of partnership

• The birth of UNDP

• The Capacity Study

• The system is dead, long live the system …

• New dimensions for UNDP

• New programs

• The golden partnership

The creation of UNDP was motivated by a post-war logic that the developing countries needed TA from a multilateral source to fill the gaps in institutions and skills required by what was, at the time, still an ill-defined development process. There were no antecedents for this kind of “free” multilateral assistance, and it took a sudden change of heart by a US president to open the way to the creation of the Expanded Programme of Technical Assistance (EPTA), the forerunner of UNDP. The EPTA helped establish the practice of pre-funded aid from multilateral and bilateral sources—a form of top-down patronage that is now taken for granted.

This chapter traces the origins of UNDP from the immediate postwar period, its formal birth in 1965 and its subsequent evolution up to the 1970s. An important part of the story has been the unsuccessful attempt to cement UNDP’s role at the center of the UN development system.

The origins of UN technical assistance

UNDP started life in January 1965 as a result of a merger of two existing funding programs: EPTA, created in 1950; and the Special Fund of 1959.1 The origins of each were themselves the result of a protracted debate about the role of the UN in development cooperation, and multilateral assistance in general.

The earliest example of multilateral TA was almost certainly under the League of Nations in the 1930s, for which provision was made under the League’s Covenant.2 An example was a request from China for advisory assistance on health and hygiene. Given the delicacies of the political situation at the time in the region—with the Sino-Japanese conflict breaking out in 1931—and Chinese concerns over sovereignty, acceding to the request took time to negotiate. Experts were sent on the strict understanding that their role was to advise rather than decide. In 1933, the first resident technical adviser was installed—a forerunner of the UN country representatives. By 1941, some 30 advisers had been fielded, all paid for by the Chinese government.3

The next examples of multilateral assistance were of a humanitarian nature, as a response to the devastation of the Second World War and the need to resettle six million displaced people in Europe. The UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was established in 1943, drawing staff from the successful Middle East Service Centre (MESC), created by the British to support the economies of that region. One of these was Robert Jackson, a towering personality in the early history of the United Nations. An Australian from a military background, he had made his name during the war through his work with the MESC, which became something of a model for later UN TA. Jackson went on to become deputy head of the UNRRA, and subsequently played several key roles under the authority of the UN Secretary-General.4 He was later to play an important part in fashioning the architecture of the UNDP.

UNRRA had a very clearly circumscribed mandate, and by 1947 it was wound up—a rare occurrence of organizational demise in the UN. Its fate was determined by ideology and the onset of the Cold War. Some in the US Congress would not countenance a United Statesbacked agency prepared to provide assistance to the Communist bloc in Europe.5 The UN was nevertheless able to redirect UNRRA’s remaining funds to several of the new agencies to support their humanitarian and TA activities, including FAO (1945), UNESCO (1945), UNICEF (1946),6 and WHO (1948).

When it came to drafting the UN Charter, some in the developed country delegations were reluctant to give economic and social issues the same priority as political issues.7 However, enlightened opinion won out in San Francisco, and the Charter’s language was explicit about the international organization’s role in supporting development. Article 55 stipulated the promotion of:

• higher standards of living, full employment, and conditions of economic and social progress and development;

• solutions of international economic, social, health and related problems; and international cultural and educational cooperation; and

• universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.

How was all this to be achieved? The specialized agencies were being provided with modest sums in their regular budgets for TA in their respective fields. In 1946, the UN Organization itself—the secretariat under the immediate authority of the Secretary-General—was allowed a small fund in its own regular budget in 1946 to undertake “advisory social welfare services,” a domain not covered by the mandates of the agencies. In 1948, the scope of these services was expanded to include economic development and public administration. Much more significant, however, was the agreement in the UN’s main development committee, the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in August 1949 to establish the Expanded Programme of Technical Assistance for Economic Development, with a significantly larger appropriation.8

The Expanded Programme of Technical Assistance

The birth of EPTA had been a matter of some debate. The aid discussion at the time was dominated by the United States, which was the only country in the 1940s in a position to provide substantial amounts of assistance, as it demonstrated with its approval of the Marshall Plan in 1948. Many in the United States were more reluctant about multilateral assistance, over which they could exert little direct control. One of the initial detractors was President Truman. However, he evidently changed his mind. In his inaugural address of January 1949, where he adumbrated US foreign policy in four points, he committed America in the first to support the UN and the specialized agencies. In the fourth, he stated:

[…] we must embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of under-developed areas […] we should make available to peace-loving peoples the benefits of our store of technical knowledge in order to help them realize their aspirations for a better life. And in cooperation with other nations, we should foster capital investment in areas needing development. […] we invite other countries to pool their technological resources in this undertaking […] This should be a cooperative enterprise in which all nations work together through the United Nations and its specialized agencies wherever practical.9

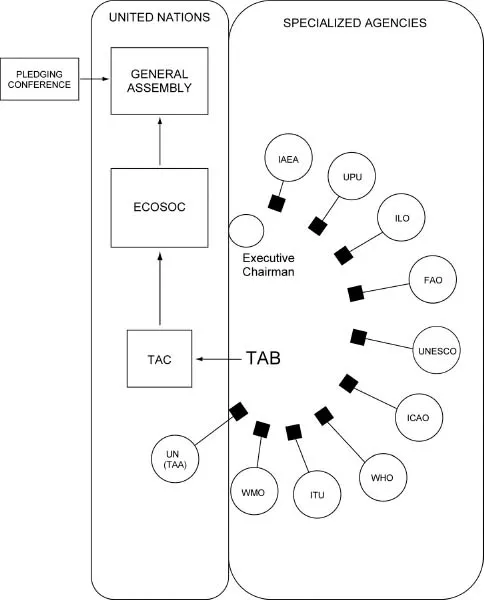

It was a clarion call for the UN. Shortly afterwards, the secretariat, with the collaboration of the specialized agencies, drew up a detailed proposal leading to the approval of EPTA that same year as a fund for a full range of TA activities. The EPTA resolution also provided guidelines on the governance and administration of the new program. ECOSOC would establish a Technical Assistance Committee (TAC) to oversee a Technical Assistance Board (TAB), chaired by the Secretary-General and comprising the heads of the specialized agencies (Figure 1.1). The TAB would be responsible for receiving requests for assistance and passing these on for approval by the TAC. In the first pledging conference in June 1950, donors provided $20 million to EPTA. It was below the ambitious target of the UN, but it was a solid start.

A key figure in this exercise was David Owen, reputedly the first person to be recruited to the UN secretariat after the war, and at the time head of the Economic Department. He coordinated the preparatory meetings for EPTA and oversaw the drafting of the blueprint. He was to become the Executive Secretary of the new TAB, and subsequently its Executive Chairman.

One of Owen’s main challenges in guiding the early stages of EPTA was the thorny problem of apportioning funds to the agencies. They were designated as beneficiaries of the new funds and they wanted to be sure of safeguarding their shares. Partly it was a matter of organizational ambition. But there was a practical need to ensure continuity in the management and staffing of their TA programs. There was protracted debate on the apportionments, which were initially among five agencies (FAO, UNESCO, WHO, the International Labour Organization (ILO), and ICAO) and the UN itself, which had established its own Technical Assistance Administration (TAA) within the secretariat, headed by a director-general. Shares were finally agreed through a clumsy process of compromise, which had as much to do with the persuasive powers of the agencies as with any more dispassionate overview of contemporary development needs. Balance is difficult in any multilateralism system. However, giving guarantees to the agencies was clearly at odds with the aspirations of developing countries to present proposals to EPTA for funding based on their own specific development priorities. During the TAC meetings in 1953, which reviewed the start-up of the new organization, Owen remarked that “logically it was extremely difficult to reconcile integrated planning within countries with the concept of a percentage allocation of funds to the specialized agencies.”10 It was agreed at ECOSOC that, from 1955, fixed shares would be ended, but to placate the agencies, they would receive not less than 85 percent of the previous year’s allocation. This constraint was abolished only in 1961.

Figure 1.1 Structure of the Expanded Programme of Technical Assistance (EPTA)

Owen helped to ensure the amplification of country views through the fielding of a growing number of TAB representatives.11 There were three at the start of EPTA in 1950, but the number grew steadily to 15 in 1952, 45 in 1958, and over 70 when UNDP was created in the mid-1960s. From the mid-1950s, ECOSOC called for a loosening of automatic agency shares in favor of more deliberate “country programming.” It was an important step toward releasing program formulation from procrustean sectoral apportionments, but in practice it did little to dampen the determination of the agencies to ensure they were present in every country allocation. These pressures were felt at the field level, where the TAB representatives became targets for agency advocacy.

Funding levels grew steadily, but continued to fall short of EPTA’s ambitions, which were inflated by agency expectations. By 1955 pledges had risen to $28 million; by 1960 to $34 million; and by 1965 to $56 million, with the United States remaining the largest contributor by far, accounting for 40 percent of the total into the 1960s. Actual contributions fell a little short of pledges, and payments were delayed, but EPTA’s funding problems were mainly the result of expectations running ahead of available resources, necessitating periodic retrenchments. Stop–go cycles have bedeviled UN system TA from the earliest stages.

A review in 1965 of EPTA’s 15 years as an independent entity revealed that the program had disbursed a total of $457 million in 150 countries, with one third of the spending in Asia. Four agencies accounted for 77 percent of the program: FAO (24 percent), UN (21), WHO (17), and UNESCO (15). Nearly three-quarters of the programmed funds (net of administrative costs) went on expert services, and the next largest share was for 31,000 fellowships awarded during that period.12 The EPTA was certainly ubiquitous, but its services were spread very thinly. It was one of the reasons why the UN sought to establish a complementary facility to support larger, multi-year projects.

The Special Fund

The Special Fund came into being nine years after EPTA, but it had much longer antecedents and it had been conceived on a much larger scale than EPTA. One of the most prominent campaigners for a UN role in development finance was the first person David Owen had asked to join him in the secretariat following his own appointment in 1946. Hans Singer was one of the early “brains” in the UN: a reputed academic,13 as well as a fount of sound ideas and proposals. Singer wrote a paper for Owen on “pre-investment,” which led to a proposal for a Special UN Fund for Economic Development (SUNFED). SUNFED would have created a single large capital investment fund supporting development projects through grants and soft loans, and it must have been part of the inspiration for Jackson’s 1959 proposal for an International Development Authority (IDA). Debate on the proposal ebbed and flowed almost throughout the 1950s, with the developing countries in support and the United States and United Kingdom against. Its critics were doubtful about the wisdom of a fund governed by the General Assembly, in which the main contributors could be outvoted.14 A satisfactory form of governance under UN auspices could certainly have been found, but the two most prominent banking nations took a conservative line, which drew them more naturally to an organization that they could control through voting shares: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank).15 There was some irony in the fact that Owen, Singer, and others in the UN had been exhorting the World Bank to commence soft lending to developing countries, against the stolid resistance of Eugene Black, its President throughout this period.

As so often with his ideas, Singer’s prescience prevailed, although not in the manner he had anticipated, and he had had in the meantime to suffer vilification by Republicans in the US Congress.16 In 1958, ECOSOC and the General Assembly had authorized the creation of a Special Fund of the UN, but with functions complementary to the TA activities of the system. In the words of General Assembly resolution 1240, the Fund “would be directed towards enlarging the scope of the UN programmes of TA so as to include special projects in certain basic fields.”17 The following year, the World Bank agreed to establish the curiously-named International Development Association specifically for the purpose of extending concessional loans to developing countries. It was not Robert Jackson’s International Development Authority, but it had many of the same objectives as SUNFED. The World Bank’s IDA was to be funded from donor contributions (“replenishments”) on a triennial basis, augmented by profits from the Bank’s other operations. The new IDA confirmed the readiness of the donor community to set up a major new funding facility within the multilateral system, but the World Bank had won the main prize while the Special Fund was seen by many as a sop for the UN. While Singer’s concerns about meeting the financial needs of developing countries through soft lending had been met, the advent of the new IDA helped to establish the World Bank—although formally a “UN specialized agency”— as a major development cooperation rival of the UN development system.

The same authorizing resolution of the General Assembly spelt out the guiding principles and criteria of the Special Fund. The “basic fields” would include mining, manufacturing, infrastructure, health, statistics, and public administration. It would finance “relatively large projects […] with the widest possible impact […] in particular by facilitat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Foreword by the series editors

- Foreword by Craig Murphy

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The origins of UNDP

- 2 The 1980s and 1990s

- 3 UNDP in the twenty-first century

- 4 Performance and results

- 5 The future of the UN development system

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access United Nations Development Programme and System (UNDP) by Stephen Browne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.