eBook - ePub

Emotion and the Psychodynamics of the Cerebellum

A Neuro-Psychoanalytic Analysis and Synthesis

Fred M. Levin

This is a test

Share book

- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Emotion and the Psychodynamics of the Cerebellum

A Neuro-Psychoanalytic Analysis and Synthesis

Fred M. Levin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is a book about cognition, emotion, memory, and learning. Along the way it examines exactly how implicit memory ("knowing how") and explicit memory ("knowing that") are connected with each other via the cerebellum. Since emotion is also related to memory, and most likely, one of its organising features, many fields of human endeavour have attempted to clarify its fundamental nature, including its relationship to metaphor, problem-solving, learning, and many other variables. This is an attempt to pull together the various strands relating to emotions, so that clinicians and researchers alike can identify precisely, and ultimately agree, upon what emotion is and how it contributes to the other known activities of mind and brain.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Emotion and the Psychodynamics of the Cerebellum an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Emotion and the Psychodynamics of the Cerebellum by Fred M. Levin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Unconscious Revisited and Reconceptualized

Chapter One

Sleep and dreaming, Part 1: Dreams are emotionally meaningful adaptive learning engines that help us identify and deal with unconscious (ucs) threats by means of deferred action plans; REM sleep consolidates memory for that which we learn and express in dreams

Fred M. Levin, Colwyn Trevarthen, Tiziano Colibazzi, Juhani lhanus, Vesa Talvitie, Jean K. Carney, and Jaak Panksepp1

“Dreams provide an opportunity to learn more about the nature of the information that is processed during REM sleep.”

Ramon Greenberg, 2003

Précis: Part 1 presents a neuro-psychoanalytic (NP) model of dreaming and its relationship to sleep, wakefulness, and the ucs. Psychoanalysts (M. Stern, 1988; Greenberg, 2003) hypothesize that when we sense ucs difficulties, an active dream life supports its resolution in real life. Specifically, dreams create “deferred action plans” that are later actualized in a manner that explores and reduces dangers. Such action plans are adaptive for both the individual dreamer and any dreaming species (Revonsuo, 2000; Revonsuo & Valli, 2000). What is learned during dreaming is consolidated by REM sleep activation (Bednar, 2003) and the new knowledge “fixed” by multiple consolidation and reconsolidation events, themselves activated by various transcription factors (Bornstein & Pittman, 1992). In Part 2, we speculate on which subsystems of the brain make what kinds of contributions to dreaming.

I. Introduction: A dreaming model as seen by neuro-psychoanalysis (NP)

The original pioneers on REM sleep memory fixation and consolidation in dreaming were psychoanalysts committed to neuroscience (Pearlman, 1971, 1973,1979; Pearlman & Becker, 1973, 1974; Greenberg & Pearlman, 1974). The newest paradigm on dreaming we owe to Solms (1997, 1999, 2003a, 2003b, 2003c; Solms & Turnbull, 2002), Panksepp (1985, 1998a, 2003, 2005a), and many others;2 it strongly supports the view of dreaming as an emotionally meaningful and psychologically adaptive phenomenon. Solms critically demonstrates that REM states and dreaming are not isomorphic but rather doubly dissociable phenomena (i.e. REM sleep can occur without dreaming, and dreaming without REM sleep). Solms'research supports the position that dreams facilitate emotional mastery over dangers and conflicts, and our learning how3 to deal with them (see also Shevrin & Eiser, 2003). Critically, Solms demonstrates that without both an intact medial ventral frontal lobe (MVFL), and parietal-temporal-occipital cortical junction (PTOCJ) dreaming cannot occur (Solms, 2003b, p. 221). Since the MVFL is associated with self-related emotional and motivational functions, and since the PTOCJ is critical for mental imagery and object relations, dreams must be deeply psychologically meaningful mental events. Moreover, as both Solms and Panksepp point out, the main candidate for providing master control mechanisms for dreaming are clearly the meso-limbic meso-cortical dopaminergic (DA) pathways, which are the same pathways associated with the SEEKING system (Panksepp, 1998a, pp. 144–163), a command system of undisputed psychobiological and psychodynamic importance. Thus, unequivocal evidence supports bridging core psychoanalytic and neuroscience contributions to understanding dreaming better than any time in recent history.

Because we see dreaming as a learning engine, we start with some observations about learning mechanisms. “Current neuropsychological research strongly supports the idea that motor activity and adaptive learning are fundamentally associated with each other. Jeannerod (1985) reviews the relevant [primary] research in this area, including prominently the work of Hebb, Held, Hubel and Weisel, and Piaget. An interesting question is why adaptive learning does not occur unless the subject initiates motor actions” (Levin, 1991, p. 224).

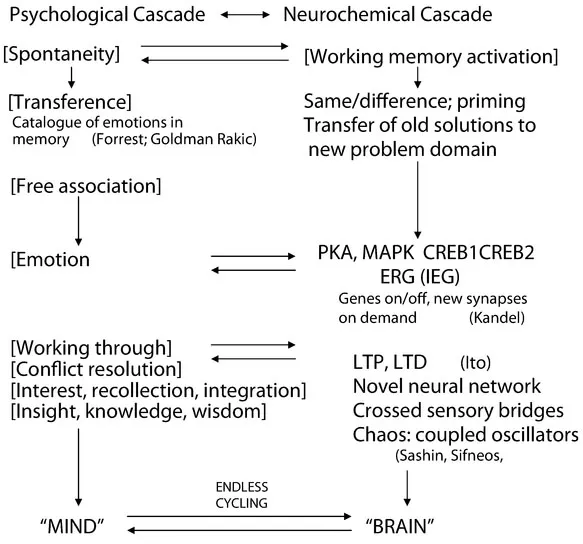

There are probably a host of factors for why taking an active stance assists learning (Levin, 1991, 1997, 2003): (1) spontaneity4 activates working memory for what we are learning; (2) activity primes memory generally, adding valuable associations; (3) our actions follow our interests, which facilitates learning by simultaneously activating the primary association cortical areas for the various sensory systems, which facilitates “aha reactions”; and (4) every action is an experiment. One of us (FML) has spent years investigating what is known about learning in terms of mind and brain correlations (Levin, 2003). Some of these factors appear in Fig. 1 (Levin, 2004b, 2005a, 2005c) which summarizes this work illustrating the emotional (psychological) cascade5 associated with learning, and the corresponding biological cascade associated with the emotional cascade (Kandel, 1983, 1998; Abel et. al., 1998). In this sense there is reason to believe that in the case of adaptive learning, mind creates brain as much as brain creates mind. This is because the new (NMDA) synapses involved in learning are on created by what is emotionally salient (emotional attention) (Levin, 2005a, 2005b, 2005c). These comments are important because they help clarify the psychoanalytic clinical experience from which our model of dreaming has grown, with due respect, of course, to the effects on our theorizing of the explosion of informative neuroscience research on the same subject.

Figure 1. Biological and Psychological Cascades

Our chapter really starts, however, from one question: What is the function of dreaming? This has been a seminal question for NP. We believe that dreams are adaptive for dreamers in at least three interrelated ways: (1) dreams facilitate learning by creating specific emotion-based action plans as probes for the discovery of the exact nature of potential dangers, for guiding the learning about contextual details, and storing this emotionally critical information within implicit (procedural) and explicit (declarative) memory systems during dreaming and waking life, respectively (Talvitie & Ihanus, 2002); (2) dreams exercise the emotional-instinctual potentials of the brain (Panksepp, 1998); and (3) more specifically, dreams can simulate threatening events, rehearse threat perception and threat avoidance, and improve self performance in dealing with threats [and with conflicts], thus ultimately improving the probability of sexual reproduction by the dreamer (i.e. they aid the survival, and we would add, the happiness, of our species) (Revonsuo, 2000). In speculating about the adaptive value of dreams, we are not necessarily restricting ourselves to the dreaming of humans.6 Indeed, there is a large literature on other animals suggesting that REM sleep is necessary for consolidating memories related to especially stressful learning situations (Panksepp, 1998, Chapter 7).

We shall review the research that bears on our central question. Some important largely neuroscientific evidence appears in Pace-Schott Solms, Blagrove and Harnad (2003). Other evidence appears in the psychoanalytic literature (Opatow, 1999; Shevrin et. al., 1996; Westen, 1999). A fair conclusion would be that there is an enormous amount of conceptual controversy in the field of sleep and dreaming, ranging from approaches such as ours (that see dreaming as both meaningful and adaptive, especially via dream exploitation of emotions) to those that assert that there is absolutely no reliable evidence supporting such a conclusion (see Walker, 2005).

The problems in sleep and dreaming research relevant to our core hypothesis are both theoretical and practical. On the theoretical side are the obvious difficulties in bridging psychoanalysis and neuroscience. All constructs, psychoanalytic or neuroscientific, need to be based upon evidence and stated in specific testable form. Asserting, for example, that an entire field lacks any scientific basis is dangerous ground. This kind of criticism has been addressed in detail by Opatow (1999) and Westen (1999) in defense of modern psychoanalytic science. Opatow has tackled the philosophy of science issues, making it clear how psychoanalysis helps us gain access to ucs fantasy and thus “acquire valid knowledge of the proximate causes of [individual] … suffering” (p. 1122). Westen has documented the very large number of independent contemporary articles on the scientific evidence for the existence of a psychological ucs. For example, Westen introduces technical evidence supporting “… that much of mental life is unconscious, including cognitive, affective, and motivational processes” (p. 1061). Westen (1999) cites research articles that are detailed empirical studies relating the ucs to such subjects as subliminal activation, the priming of various kinds of memory (implicit, explicit, associative, etc.), both as manifest in the activity in healthy individuals as well as in amnesics, prosopognosics, and other brain-injured populations (research in these latter areas also appears in depth in Solms, 2000). Westen and Opatow together exemplify the modern psychoanalytic scholarly world, which is on ignored in attacks on Freud’s earliest thinking as though it perfectly represents current psychoanalytic scientific opinion (it most certainly does not). There is little doubt that it is easier to attack Freud than deal critically with contemporary psychoanalytic data on scientific grounds. Fortunately, correspondingly ill-argued attacks from psychoanalysis, such as the argument that neuroscience is largely irrelevant to analytic studies, have dramatically decreased in the past decade.

Part of the practical problem for neuroscientific dream research arises from the fact that we currently have no empirical access to non-REM dreams in animals. Therefore, among the two major varieties of dreams, REM dreams and non-REM dreams, and the mixed variants combining these two types (as a third variety), it is only for the REM dream category that we can easily identify dreams empirically (because of the obvious eye movements). Therefore, our chapter focuses exclusively on REM dreams. On the positive side, however, there is a significant consensus that REM dreaming is more emotional. We should thus be better able to substantiate our points about the meaningfulness and adaptiveness of REM dreaming, which on seems identified by the dreamer’s affects. The fact is that most of the hard neuroscience data on REM dreaming and the abundance of well-controlled experiments comes from animal research. In other words, it is to our advantage to deal primarily with emotion-laden REM dreaming because such dream emotions likely express valuable information, or important content issues of interest to neuro-psychoanalysts. It should be equally obvious that it helps that REM dreaming can and has been objectively studied simultaneously at both psychological and hard-neuroscience levels in man and animals.

Although much of the dream research reported in Pace-Schott Solms, Blagrove, and Harnad (2003) appears to take the importance of emotions for granted, nevertheless, a significant minority feels emotions (and even dream contents) can safely be ignored in examining dreams! Obviously, we disagree with this assertion. “As dream commentators have long noted,7 with Revonsuo (2000, [Revonsuo & Valli, 2000]) taking the lead among … present authors, emotionality is a central and consistent aspect of REM dreams” (Panksepp, 2003, p. 200). Contents are also critical for determining the meaning of dreams clinically and experimentally. From our perspective, dreams also have an evolutionary, and not just an individual adaptive effect. Our theorizing and Revonsuo’s threat simulation theory (TST) are nearly identical, although TST and our theorizing developed completely independently of each other. We also define “danger” as relating to internal feeling states and conflicts along with external dangers. Dangers have a natural close connection in the dreamer’s need to struggle with life events, and maintain various internal equilibria simultaneously (Shevrin & Eiser, 2003, p. 218).

The testing of TST theory (Revonsuo et al. 2000) has involved detailed collections and content analysis of threatening events in dream reports across a wide range of subjects. Attention was paid to the nature and source of the threatening event, its target, severity, as well as to the subject’s participation and reaction to the threat (i.e. its consequences). One key prediction was that if TST theory is correct then one should find a high frequency of threatening events in the dreams of normal subjects, relative to the (lower) frequency of such threats in the waking life of the same individuals. This turned out to be exactly the case. Revonsuo et al. further correctly predicted that the dangers would be to the self and to those emotionally close to the self, relatively realistic, and that the dream self should routinely take at least some defensive action against any impending threats. Importantly, Revonsuo et al.’s theorizing, based upon empirical evidence and now significantly experimentally confirmed, contradicts the views of those dream researchers who have insisted that dreaming is chaotic and biologically an epiphenomenon (i.e. functionless, and meaningless) (Hobson, Pace-Schott & Stickgold, 2003; Pace-Schott & Hobson, 2000). It is also ironic that the critics of the meaningfulness of dreams sometimes ach the word “chaos” to dreams, when in fact the modern technical meaning of the word “chaos” refers to a phenomenon (e.g. chaotic attractors in nonlinear dynamics) that expresses deeper hidden meaning or order that underlies a surface of merely apparent meaninglessness or disorder!

The core new element in our contribution is twofold: (1) we are applying modern psychoanalytic learning theory to understanding the adaptive aspects of dreaming, and analyzing things simultaneously from an experiential (psychoanalytic) and a (neuroscientific) empirical perspective (Levin, 1991, 2003); and (2) our idea that deferred action plans are critical, when activated, to the learning from dreams that results in adaptive shifts in the self, is a novel contribution with clinical implications and a biological causation that is increasingly known. We are asserting that one critical way such adaptive learning follows from dreams is that dreaming generates strategies for actively checking upon and thus responding to potential dangers, including those emanating from internal psychological conflicts, and that it is not until certain actions are taken and new important threat-related information discovered (confirmed or disconfirmed) that the final phase of learning occurs in the form of adaptive adjustments in the self. Such adaptive adjustments obviously involve changes at fundamentally different levels of analysis: at the cellular level involving various transcription factor effects on genes; at the level of neural networks, involving memory consolidation8 and reconsolidation or extinction; and within the personality, involving adjustments to emotional and motivational processes.

II. A clinical example and definition of "deferred action planning" in dreams

Darlene is a 26 year-old medical student in psychoanalytic treatment. She had the following dream: “I am in a kind of SUV. I am with a nutsy friend who is driving, and he decides we will drive over some roadblocks in this desert area. He enters this blocked off area without any concerns for our safety. Finally we come to a military base where we are captured. They take him away and I can tell from how he looks when he comes back that he was tortured. The guy who did it to him was smiling when he took him away. I wish him well, but my status is unclear.”

When asked for associations to the dream imagery she comments immediately on her conscious impulse to go against the wishes of a member of her family. The friend in the dream reminds her of her analyst, giving her dangerous permission to proceed against her relative, but Darlene is afraid of taking initiatives. Her relative would be strongly against Darlene’s wish to let her classmate fix her up on a date. Her relative’s anger over this seems almost paranoid. But how could she go against this relative? She wants to go out on the date, but it’s like running the risk of being thrown out of her family. In spite of this, she can see that as her analysis proceeds she is gaining some additional confidence in herself, and there is more of a possibility now than ever before that in the near future she is likely to violate some of the internal rules she sets up for herself, such as her rule never to disobey this particular relative. She can barely stand the pain of feeling so much trapped between her wish to date only people who are acceptable to her family vs. her desire to live her own life! She knows that a decision needs to be made, but it is so very hard to make. She is grateful for the time and space the analysis p...