Vigilantism against Migrants and Minorities

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Vigilantism against Migrants and Minorities

About this book

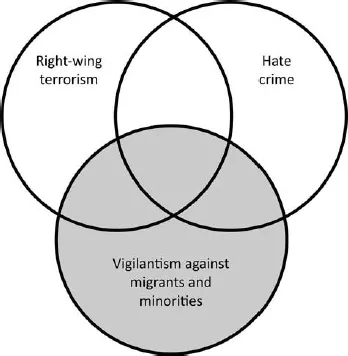

This edited volume traces the rise of far right vigilante movements – some who have been involved in serious violence against minorities, migrants and other vulnerable groups in society, whereas other vigilantes are intimidating but avoid using violence.

Written by an international team of contributors, the book features case studies from Western Europe, Eastern Europe, North America, and Asia. Each chapter is written to a common research template examining the national social and political context, the purpose of the vigilante group, how it is organised and operates, its communications and social media strategy and its relationship to mainstream social actors and institutions, and to similar groups in other countries. The final comparative chapter explores some of the broader research issues such as under which conditions such vigiliantism emerges, flourishes or fails, policing approaches, masculinity, the role of social media, responses from the state and civil society, and the evidence of transnational co-operation or inspiration.

This is a groundbreaking volume which will be of particular interest to scholars with an interest in the extreme right, social movements, political violence, policing and criminology.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

VIGILANTISM AGAINST MIGRANTS AND MINORITIES

Concepts and goals of current research

Why research vigilantism against migrants and minorities?

- How do these vigilante activists operate, and how are they organized? Can we develop a typology of modus operandi?

- What are the reasons, goals or purposes of this form of vigilante activism? We will explore official justifications, internal group strategies, as well as individual motivations.

- Under what kinds of circumstances do these vigilante activities emerge, flourish or fail? What are the facilitating and mitigating – or permissive and repressive – factors?

- What are the vigilante groups’ relationships with the police, other authorities and political parties, and how does it influence the group and its activities?

- How can our empirical material and findings contribute to the broader academic discussion on the phenomenon of vigilantism?

Conceptualizing vigilantism

- it involves planning and premeditation by those engaging in it;

- its participants are private citizens whose engagement is voluntary;

- it is a form of ‘autonomous citizenship’ and, as such, constitutes a social movement;

- it uses or threatens the use of force;

- it arises when an established order is under threat from the transgression, the potential transgression, or the imputed transgression of institutionalized norms;

- it aims to control crime or other social infractions by offering assurances (or ‘guarantees’) of security both to participants and to others

- External justifications present the official mission of the group towards the public, the media and authorities: to protect the community against certain crime threats that the police and other authorities do not have the capacity (or will) to handle alone. These justifications are tailored to resonate with widely held concerns in society (e.g. on crime or migration) and issues high on the news media’s agenda. Vigilante groups claim to represent the interests of society in order to control crime or other social anomies.

- Group strategies are the internal reasoning for why leaders believe it will serve the interests of the group to engage in vigilante activities, typically to attract media attention and public support, promote the organization and mobilize new members, to maintain group cohesion, or to undermine the legitimacy of the government. It can also serve as a training activity for paramilitary groups. These reasons are not meant for public consumption.

- Individual motivations are the drivers behind individual participation in vigilante activities and groups. Such motivations may have to do with a desire to improve one’s personal identity and status, in particular by individuals who have a tarnished reputation as trouble-makers or criminals. Others may be attracted by the militarism or belonging to a strong group. These individual motivations are usually not fit to be publicized, as they may undermine the official justification. However, some participants may also be driven by motives that are congruent with the official mission of the group.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Preface

- 1. Vigilantism against migrants and minorities: Concepts and goals of current research

- 2. Ku Klux Klan: Vigilantism against blacks, immigrants and other minorities

- 3. Jewish vigilantism in the West Bank

- 4. Protecting holy cows: Hindu vigilantism against Muslims in India

- 5. Violent attacks against migrants and minorities in the Russian Federation

- 6. Anti-immigration militias and vigilante groups in Germany: An overview

- 7. Vigilante militias and activities against Roma and migrants in Hungary

- 8. Vigilantism against migrants and minorities in Slovakia and in the Czech Republic

- 9. The Minutemen: Patrolling and performativity along the U.S. / Mexico border

- 10. Vigilantism against ethnic minorities and migrants in Bulgaria

- 11. Vigilantism in Greece: The case of the Golden Dawn

- 12. Forza Nuova and the security walks: Squadrismo and extreme-right vigilantism in Italy

- 13. Beyond the hand of the state: Vigilantism against migrants and refugees in France

- 14. Vigilantism in the United Kingdom: Britain First and ‘Operation Fightback’

- 15. The Soldiers of Odin Finland: From a local movement to an international franchise

- 16. Sheep in wolf’s clothing?: The taming of the Soldiers of Odin in Norway

- 17. The Soldiers of Odin in Canada: The failure of a transnational ideology

- 18. Pop-up vigilantism and fascist patrols in Sweden

- 19. Comparative perspectives on vigilantism against migrants and minorities

- Index