- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Close Relationships

About this book

This multidisciplinary text introduces the concepts, methodologies, theories, and empirical findings of the field of interpersonal relationships. Information is drawn from psychology, communication, family studies, marriage and family therapy, social work, sociology, anthropology, the health sciences, and other disciplines. Numerous examples capture readers' attention by demonstrating how the material is relevant to their lives.

Active learning is encouraged throughout. Each chapter includes an outline to guide students, key terms and definitions to help identify critical concepts, and exploration exercises to promote active thinking. Many chapters include measurement instruments that students can take and score themselves. A website for instructors features a test bank with multiple-choice and essay questions and Power Points for each chapter.

This text distinguishes itself with:

- Its focus on family and friend relationships as well as romantic relationships.

- Its multidisciplinary perspective highlighting the contributions to the field from a wide array of disciplines.

- Its review of the relationship experiences of a variety of people (of different age groups and cultures; heterosexual and homosexual) and relationship types (dating, cohabiting, marriage, friendships, family relationships).

- Its focus on methodology and research design with an emphasis on how to interpret empirical findings and engage in the research process.

- Cutting-edge research on "cyber-flirting" and online relationship formation; the biochemical basis of love; communication and social support; bullying and peer aggression; obsession and relational stalking; sexual violence (and marital rape); and grief and bereavement.

The book opens by examining the fundamental principles of relationship science along with the research methods commonly used. The uniquely social nature of humans is then explored including the impact relationships have on health and well-being. Part 2 focuses on relationship development—from attraction to initiation to development and maintenance as well as the factors that guide mate choice and marriage. The development of relationships in both friendships and romantic partnerships is explored. Part 3 examines the processes that shape our interpersonal experiences, including cognitive (thinking) and affective (feeling) processes, communicative and supportive processes, and the dynamics of love and sex. The book concludes with relationship challenges—rejection and betrayal; aggression and violence; conflict and loss; and therapeutic interventions.

Intended as a text for courses in interpersonal/close relationships taught in psychology, communication, sociology, anthropology, human development, family studies, marriage and family therapy, and social work, practitioners interested in the latest research on personal relationships will also appreciate this engaging overview of the field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Principles of Relationship Science

Chapter 1

Basic Facts and Key Concepts

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Fact #1: Relationship Scientists Study Relationships | ||||

Interaction: The Basic Ingredient of a Relationship | ||||

Two Additional Ingredients | ||||

Establishing Interdependence | ||||

Fact #2: Relationship Scientists Study Certain Types of Relationship | ||||

Lovers, Family, and Friends | ||||

Close Relationships | ||||

Subjectively Close (Intimate) Relationships | ||||

Behaviorally Close (Highly Interdependent) Relationships | ||||

Fact #3: Relationship Science Is Not Easy | ||||

Societal Taboos Against the Study of Relationships | ||||

Relationships are Complex | ||||

Relationship Phenomena are Multiply Determined | ||||

Relationship Science is Multidisciplinary | ||||

Fact #4: Relationship Science is Important | ||||

Summary | ||||

Key Concepts | ||||

Exploration Exercises | ||||

FACT #1: RELATIONSHIP SCIENTISTS STUDY RELATIONSHIPS

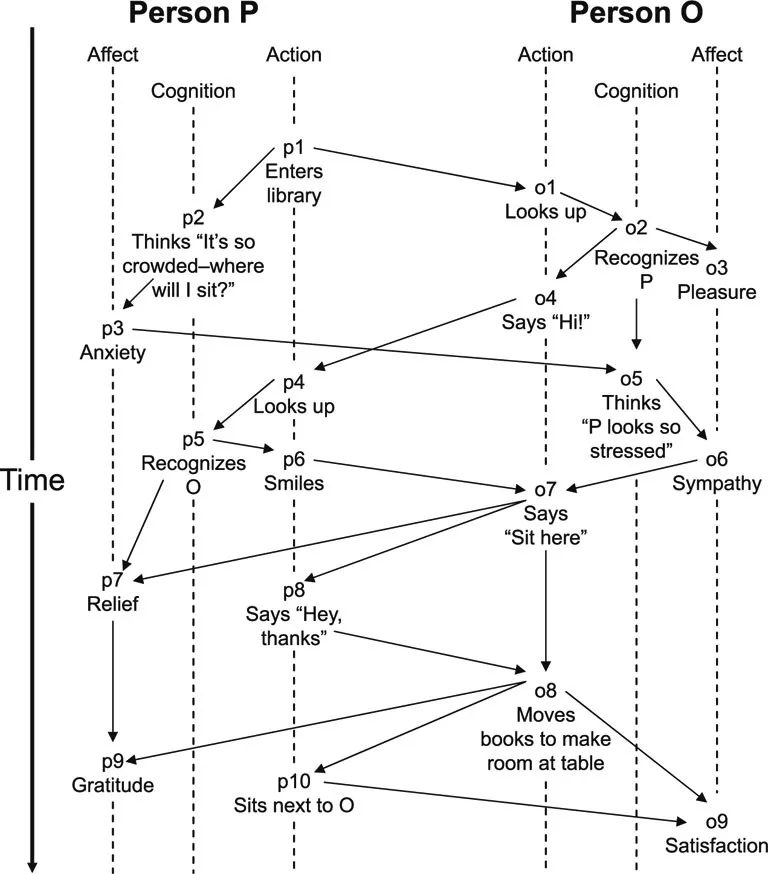

Interaction: The Basic Ingredient of a Relationship

Two Additional Ingredients

Table of contents

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Preface

- About the Author

- PART I Principles of Relationship Science

- PART II Relationship Development

- PART III Relationship Processes

- PART IV Relationship Challenges

- References

- Author index

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app