![]()

1

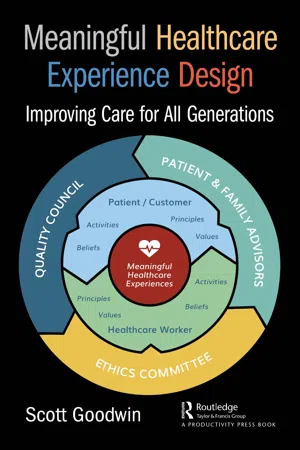

Meaningful Healthcare Experiences

![]()

Chapter 1

Meaning in Life as Meaning in Healthcare

One of the fastest ways to shut down a routine conversation is to ask someone the philosophical question of the ages, “What is the meaning of life?” One of the best questions to start a conversation about healthcare is to ask, “How does a healthcare experience contribute to meaning in your life?”

Meaning in life (not meaning of life) and meaning in healthcare begin with a sense of how each of us experiences and interprets our reality of which healthcare is a part. Sociologists Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann authored the work Social Construction of Reality (1966). They offered the observation that “everyday life presents itself as a reality” (p. 34). We are “wide-awake” when we experience reality, and this state of being awake and able to perceive reality is “taken by you and me to be normal and self-evident” and it “constitutes our natural attitude” (p. 35). In a mysterious way, we encounter the world around us. Moment by moment we experience the world as an “ordered reality” (p. 36), and as long as everything is going smoothly, our “natural attitude is the attitude of common-sense consciousness. The reality of everyday life is taken for granted as reality” (p. 37).

We think of ourselves and the world around us as familiar and something we share with other people in the “normal, self-evident routines of everyday life” (Berger & Luckmann, 1966, p. 37). As they describe it, “As long as the routines of everyday life continue without interruption they are apprehended as unproblematic” (p. 38). When something happens, however, that is not routine and is not part of the familiar rhythm of our lives, our awareness and perception of reality changes. When a situation arises that draws my attention to a part of my reality that suddenly seems odd or there is a problem that I need to address, my attitude changes. I focus my attention and begin to “seek to integrate the problematic sector into what is already nonproblematic” (p. 38). I do this, according to Berger and Luckmann, by using my store of common-sense understanding that is the way I experience my reality every day and that I share with other people.

Based on the way we are oriented toward our everyday existence as described by Berger and Luckmann (1966), healthcare services fall into the problematic aspect. They require that we shift our attitude about our reality from the familiar rhythm of life and routines to an attitude in which we identify a sector of our lives for special attention during that period in which healthcare is a concern. As a way of illustrating this, let’s take a routine healthcare procedure such as an intravenous (IV) catheter insertion for the administration of a medication or fluids to address a health issue. Describing the actual insertion helps to replicate the way our attention is focused on the situation during the actual procedure. Here is the insertion of the needle and catheter as described by the steps followed by the nurse performing the insertion:

Using your non-dominant hand, stretch the skin taught and stabilize the vein 4–5 cm below the insertion site, taking care not to contaminate the point of insertion.

Holding the over-the-needle catheter between the thumb and the middle finger, with the bevel up at a 15 ° –20 ° angle, pierce the skin directly over the vein until a flashback of blood is visible.

Drop the angle of the catheter a few degrees and advance the catheter with the needle by a few millimeters to ensure that the tip of the catheter has passed into the vein.

Using the index finger, advance the hub of the catheter fully into the vein, holding the needle steady.

While stabilizing the needle and catheter with the dominant hand, release the tourniquet with the non-dominant hand (JoVE Science Education Database, 2019).

If you have ever had an IV catheter inserted into you or performed the procedure, reading the brief description of the insertion probably brings back memories of this experience for you.

This frequently repeated procedure is a routine part of healthcare, and it displays so much of what we experience as the reality of healthcare. It happens in a place that is not a place that most people visit daily and the trip to the location requires planning. It involves two people who are probably strangers and unfamiliar with each other. It requires a process of registration, preparing materials and the room and conversations about the purpose of the procedure, and the way it will occur. The two people involved in the actual procedure come close enough to each other that the warmth of their bodies is discernible. This is an intimate space that is carefully guarded in most situations to prevent the intrusion of strangers. The procedure involves pain and has the potential to result in injury if not performed correctly.

As these two people meet and the procedure is performed, there are three perspectives with this experience. The three perspectives include the person receiving the IV, the person inserting the IV and delivering the care, and the healthcare facility in which it occurs. If we explore these perspectives and how they relate, we begin to develop a sense in which healthcare is a problematic aspect of our existence as identified by Berger and Luckmann (1966) and needs to be viewed as different from our routine. As a non-routine part of our life, the two people interact and seek to discover the meaningfulness of the experience that they are creating so that it can be incorporated into their understanding of reality.

The people involved in the procedures meet in a room. The act of inserting the IV and receiving the solution brings them together to share this experience. Though this is a frequently performed procedure, it still makes them at least slightly anxious. They are focused on this event not as routine or common-sense reality, but as a problem and a way to address a problem. They have arrived at this moment through a series of events, decisions, and actions that resulted in a sharp needle insertion into someone’s arm. Where did they come from and how did they get to this point of interacting with each other?

The person receiving the IV medication or solution has arrived at the facility from home or another place by car or ambulance through a series of events that stretch back to an accident or to a visit with a practitioner that led to the need for an IV to be inserted at this time and in this place. Family and others may be aware of the procedure and expressed concerns or support and hope that it would go well. Following instructions from a variety of people in the hospital or emergency department (ED) or clinic, the person signed papers, read signs, traveled down halls, entered rooms, may have changed clothes and perhaps had vital signs taken and used the bathroom. Lying in a bed or a recliner, time was spent looking around the space, waiting and anticipating the procedure, and what would follow afterward. There are possible thoughts of a meal missed and the disruption of the normal routine due to the health concern. Fear, hope, anxiety, and other emotions increase and diminish with the flow of time.

The person inserting the IV arrived at the facility from home or another place by car or bus or other transportation. Routine activities of daily life such as choosing clothing, eating a meal, caring for children or spouse, and other activities preceded the arrival at the facility. Greetings from others in the hall, documenting time of arrival, and following the familiar route through the building and rooms precede the arrival at the place where the work is performed. Routines of obtaining information, setting priorities, searching for supplies, and asking questions of others create the rhythm of the workflow that is performed through well-practiced steps.

As the work ahead begins to take shape, thoughts of what could happen as well as concerns with anything missed in the morning process of arrival run through the mind. The momentum of the day accelerates with possibly putting on protective clothing, gathering supplies, handwashing, and other activities that are part of the work about to begin. Walking into the room, simple introductions are exchanged and the steps that form the procedure enter a familiar pattern of providing information, answering questions, arranging materials, and preparing for the IV insertion.

From different points in their lives, these two people arrived in this room inside this building at this time to accomplish this procedure. The building where they meet is part of an organization that may have come into existence years before. The people in the community took actions to create this building because they felt there was a need for an organization and a space in which a procedure such as an IV insertion could occur. They found enough money to build it and architects to translate their ideas into reality. The building emerged and people came together to work in the building and to give life to the organization. The community recognized the building and the organization as a healthcare facility and sought services within its walls.

As these two people meet in this room, they hold their own understanding of this moment and what they believe is happening and how it makes sense in their lives. The person receiving the IV believes that the room is the appropriate place for this action. The person approaching and preparing to insert the IV is recognized as someone who can perform the procedure and permitted to come into the intimate space of the person receiving the IV. Though the procedure involves some pain, this is accepted as meaningful because the action and the anticipated result are consistent with the goals valued by the person receiving the IV. The overall sense conveyed by the procedure and the actions of the person delivering the care is that the person receiving the IV has significance as a person.

The person preparing to insert the IV believes the actions are consistent with memories and training and the reason for being in the room with the person receiving the IV. Entering the intimate space of the person and causing pain is part of the purpose that brings them together in the room. The result of the insertion and all the preparation that went before to create a functioning IV is a valuable professional goal that the person inserting the IV hopes to accomplish to enable the care of the person to continue. Engaging in this work and performing this action are significant because they are based on the fundamental principles that make work and life meaningful as contributing to the well-being of others.

As they meet in the room and share the experience of the IV insertion, they give expression to the beliefs that are consistent with the plans and goals that were part of the origin and prior history of the organization and building that surround them. The delivery of this healthcare service was envisioned as the purpose of the organization and structure and the goal of providing care to people who need it. Providing the space and materials and people to perform the service accomplishes the goals that were valued as the motivation for the creation of the building and organization. The principles of the people who operate the organization are fulfilled as the organization provides the setting and resources that contribute to the well-being of the people who come there to receive care.

In the interaction of the insertion of an IV within a healthcare organization, the confluence of the perspectives of two people and the organization creates a healthcare experience. This is a microcosm of the overall nature of healthcare and the structure within which healthcare experiences derive their meaning. Understanding the convergence and the alignment of the perspectives involved in these procedures forms the basis for the design of meaningful healthcare experiences.

In recent years, psychologists working in the field of Positive psychology have recognized that meaning in our lives is important to our psychological well-being. The application of these views to healthcare provides a valuable perspective for recognizing that healthcare experiences are a part of our lives that are often “interruptions in the continuity” of our lives and therefore viewed as problematic. Our natural response is to seek ways to use our common-sense knowledge of reality to “integrate the problematic sector into what is already unproblematic” (p. 38). By this, we understand that we seek to find meaning in our healthcare experiences that correspond to meaning in our lives.

When talking about meaningful healthcare experiences, the understanding of the word “meaningful” is an important first step. According to psychologists Frank Martela and Michael Steger, the word “meaning” comes from the Old High German word “meinen,” translated as “to have in mind” (Martela & Steger, 2016, p. 537). They note that “this already reveals that meaning is tied up with the unique capacity of the human mind for reflective, linguistic thinking” (p. 537). The outcome of reflection is “our mind’s capacity to form mental representations about the world and develop connections between these representations” (p. 537). They interpret meaning as “representations of possible relationship among things, events, and relationships.” Martela and Steger argue that when we ask what something means, we are trying to locate that something within our web of mental representations. “Meaning is about mentally connecting things. This is true whether we ask about the meaning of a thing or the meaning of our life” (p. 537).

Another way to refer to the “web of mental representations” is as “meaning frameworks” (Martela & Pessi, 2018, p. 2). These frameworks “are built up from the generalizations that we make about our own past experiences” and “they are highly influenced by our society, culture and upbringing from which we acquire our vocabularies, values and making sense of the world” (pp. 2–3). We construct our meaning frameworks and impose them on the world and “they help us to make sense of our current experience, give us direction about what goals and aims to pursue and guide us about what is valuable and what really matters in life and the world” (pp. 2–3).

The generalizations that arise out of our past experiences may be described as beliefs. “A belief is a mental architecture of how we interpret the world” (Alok Jha, 2005). As we experience life in all its many manifestations and react to our experiences, we create memories that ultimately can aggregate into beliefs. These beliefs form the generalizations that become part of our meaning frameworks and shape our emotions (Lawson, 2002).

Kathleen Taylor, a neuroscientist at Oxford University, as cited by Jha (2005), considers “beliefs and memories” as very similar. She describes a process where memories are formed in the brain through networks of neurons that are activated in response to an event. The more times this happens, the stronger the memory it creates. Peter Halligan, a psychologist at Cardiff University, as cited by Jha (2005) says that belief takes the concept of memory a step further. “A belief is a mental architecture of how we interpret the world.” Beliefs also provide stability. When a new piece of sensory information comes in, it is assessed against these knowledge units before the brain works out whether it should be incorporated.

Psychologists Login George and Crystal Park (2016a) define “meaning frameworks” as the “web of propositions that we hold about how things are in the world and how things will be” (p. 206). Meaning frameworks are made of the “implicit and explicit propositions abstracted from our experiences” that form “mental representations of expected relationships among people, places, objects and ideas” (p. 207). They “contribute to a sense of meaning in life” according to George and Park, in that “the propositions we hold about the world may contribute to our sense that life makes sense, is directed and motivated by valued goals and matters” (p. 207). They contend that meaning frameworks that are consistent and coherent complement an individual’s sense of comprehension. The meaning in life component of purpose is supported by meaning frameworks that “specify worthy high-level goals that are central to one’s identity and reflective of one’s core values” (p. 207). Finally, a sense of mattering or significance may be complemented by meaning frameworks that “suggest that one’s life is of significance, importance and value in world” (p. 207).

Martela and Pessi state that “meaning is descriptive” in that “it tells us about the specific meaning framework” while “meaningfulness is evaluative” and based on how well something fulfills certain values and characteristics (p. 3). Their view is that “meaningfulness is primarily a type of feeling we have” that arises when we think about our something such as our life or our work. The meaningfulness is based on how strong the feeling is present in our recollected experiences. They associate this “subjective interpretation of meaningfulness” with psychological research related to meaning in life as well as meaning in work in that “both are about the experience of meaningfulness” (p. 3).

Meaning in life as an area of focus in Positive psychology traces its origins to work by Victor Frankl, holocaust survivor and psychiatrist, who is widely considered to be a seminal figure in raising the question of meaning as it is experienced in life through his book, Man’s Search for Meaning (2006). He personally experienced significant tragedy in his life during World War II. He grew up in Austria, and he, his wife, and parents were sent to concentration camps by the Nazis in 1942. His parents and his wife died in the camps, but he survived and used his experiences during the war as the basis for the development of a psychological therapy that he called “logotherapy” to help people understand importance of their search for meaning in their lives.

“Man’s search for meaning,” according to Frankl, “is the primary motivation in his life…” (Frankl, 2006, p. 99). He refines this view by stating that “What matters…is n...