![]()

1 Introduction

This chapter sets the background for the book, starting with a brief review of the concepts of spatial planning and development. Then we shift our focus on the long-lasting concern about the process of planning, or ‘how to plan’, as well as ‘what it takes to plan well’ – that is, the competences of planners that make plans better and their work easier. The chapter closes with some notes about the approach of the book, as well as its content.

Spatial planning

Let us begin with an overview of spatial planning. Interestingly enough, both space and planning have different interpretations for people across the globe and through time – and so does ‘spatial planning’. To understand the essence of space, how it can be perceived, and how it can be shaped conveniently, people often have recourse to metaphors from more familiar experiences. But still, perhaps the only common feature of spatial planning is diversity – people shape their places almost on a ‘per case' approach.

Spatial planning is practised at various scales, and their coordination is a special challenge. At the appropriate aggregation (or abstraction) level for each scale, guidance documents – whenever they exist – capture the spirit of the place at a given time, offer a vision for its future, and give some indications for the next steps forward. Thus, development can be ‘managed’ – which is an integrated approach to combine encouragement and restrictions. A special feature of the planning operation is the fact that most of the times it is carried out amidst a barrage of critiques from academics, other practitioners, and the broader community, regarding the process or the outcomes of the planning operation, or the specific choices of the planners or the decision-makers. Let us now see this background to spatial planning in more detail.

Concepts in flux

The concept of spatial planning shows variations across time, and also across space (both as location and scale) and cultures. The central theme is ‘space’ – not the ‘outer’ space, as the physical universe beyond the Earth's atmosphere, but the land on Earth, which is indeed of prime importance to people: this is where we reside, work, and spend our lives. Alternative expressions or synonyms reveal nuances about what ‘space’ means to people – for instance, by saying ‘place’, ‘home’, ‘home town’, ‘location’, ‘area’, ‘locale’, ‘environment’, ‘site’, ‘region’, or ‘zone’, among many more options, we indicate a proper scale, content, and degree of affection to space.

If space has many different expressions and meanings, then planning has its own variety. The general idea of planning appears in many contexts to be a ‘preparation’, denoting some forethought or anticipation about the future – not so much passively as to prepare for ‘what the future may bring’, but more actively as to ‘what we wish or need to do’ (for the future to be the way we want it). Besides the specialisation of ‘spatial planning’, there are other designations such as physical planning, community planning, strategic planning, local planning, transport planning, development planning, retail planning, business planning, and many more. And within each one of these, including spatial planning, there are many different methods, or ways of proceeding, according to the cultural context, the academic and professional traditions of the participants, and the legal system in which planning takes place.

In older perceptions, but not too long ago – which may still be valid for some – spatial planning had the role of land-use regulation through prohibitions and obligations. In the same spirit, development was – metaphorically and literally – also based on land, as ‘the carrying out of building, engineering, mining or other operations in, on, over or under land, or the making of any material change in the use of any buildings or other land’ (Cullingworth and Nadin 1994: 80). One of the milestone planning documents in the UK, the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, defined development plans as ‘indicating the manner in which a local planning authority propose that land in their area should be used’ (HMSO 1947: 4).

Space was explored in glorious studies during the twentieth century by a number of ‘space specialists’ – for instance, architects such as Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Walter Gropius – who managed to project their futuristic visions into real estate. Appearance, structure, and function were of prime concern in these studies and applications, and their limited scale created perfect ‘microcosms’ that were models for ‘real life’. However, there is a difference between the small-scale models and large-scale applications: large scales imply not only more system elements, such as land, people, buildings, as well as energy and matter throughput, but also more complexity in the way this increased number of system elements interact. Thus, larger scales put a significantly larger demand on our understanding, which is required if we are to exercise effective management or governance. For instance, while in a ‘microcosm’ model the provision of energy is easily resolved by adding an electrical ‘input’ point, large-scale models include what is on the other side of that ‘input’ point, such as the facilities that transform chemical or mechanical forms of energy into electricity, plus all the side-effects of that transformation.

Over the years, the abstraction or modelling of architectural microcosms regarding space (such as buildings, neighbourhoods, highways) was enriched with those aspects of reality such as management or governance, including social and economic policies, as well as other larger-scale physical arrangements, for instance regarding mobility, communications, and energy provision. After many years of experience, thought, and debate, spatial planning tends to integrate people more realistically, including the fact that they have will, interests, initiatives, and behaviours, and that they also participate in planning in their own special ways.

Recent perceptions of spatial planning are more ‘organic’ or ‘systemic’, recognising the relationship between everything that exists in space and in the way that it functions together as a whole (on any scale), so planning certainly needs more attention than mere regulation or appropriate design can offer. In fact, innovative interpretations of spatial planning go beyond the arrangement of space – such as ‘spatial design’ or the extension of architecture towards larger scales – to include human activity in space, often starting as ‘deeply’ as motives and objectives (United Nations 2008). The extension of interest towards human activity is evidenced, for instance, by the dual strategic-spatial expression of sectoral policies (for example, housing, health, transport, energy). In the European Union, for example, spatial planning has started to exhibit considerable formal integration of social, economic, environmental, and infrastructure aspects in the last few years (European Commission 1997: 34). Including human activity within the scope of spatial planning presents a unique opportunity for the coordination of activities – not only in the way they are conceived or implemented in space and time, but also regarding synergies and conflicts in their objectives and proposals for action.

In most cases, spatial planning is guided by legal frameworks – or, simply, by a set of laws that regulate the activity. Besides guiding spatial planning, these laws also reflect the interpretation of the concept in any particular time and space. Thus, legal systems that have undergone recent reforms – ‘updates’ or modernisation – have shifted the focus of spatial planning from the older land-use model to a more integrated approach (United Nations 2008: 19).

Recourse to metaphors

To understand key concepts and relationships in spatial planning, such as the nature and qualities of space, the perception and storage of information, and how space can be shaped conveniently, people often have recourse to metaphors from more familiar experiences. It is interesting to note that after the use of some metaphors, the terminology adopted in spatial planning is the same as that of the original context of the metaphors – let us consider some cases.

The ‘body and soul’, or medical metaphor

The capacity of humans to abstract from the ‘physical’ reality is remarkable, and well evidenced in the development of civilisations and cultures, ideas and a variety of other mental models, systems of ideas (such as philosophical theories), communication systems (such as human languages), logic and argumentation, and means of expression of sentiments such as art. If the abstract reality lived through any of the above represents our ‘soul’, then the original physical reality represents our ‘body’, where the ‘soul’ physically resides. We know from the human experience that both body and soul have their own importance and each one deserves special attention. In this body and soul metaphor, spatial planning is about the ‘body’, which has shape, structure, and function, and we live in it. In the same way that people may care for their bodies, and there are also professionals who are officially in charge of that – medical doctors, that is – the metaphor continues that regarding physical space these professionals are the spatial planners. This parallelism between medical doctors and planners is often implicit, but it has a visible interface: the ‘diagnostic’ studies that a number of spatial planners carry out, just like medical doctors do. Alternatively, besides the medical metaphor, the personification in the ‘body and soul’ metaphor probably reminds of the Gaia hypothesis (Lovelock 1995).

Box 1.1 The Gaia hypothesis

The controversial Gaia hypothesis views the Earth as a single organism. The hypothesis is based on the existence of feedback mechanisms and, to a certain extent, self-regulation in both biological and ecological systems, such as the Earth – hence, the idea that Earth is like a super-organism and must be taken care of as if it were ‘alive’.

Unlike the Gaia hypothesis, the ‘body and soul’ metaphor does not have to be used at the global scale. The ‘body’, or space, can be considered at any scale – somehow like fractals (see Box 1.2). Not all bodies are the same, so they have different needs, ‘happy states’, etc. This diversity creates a differential intervention, so the methodology and content of planning varies significantly across cases. Also, various bodies can (and do) interact – we know from environmental disasters, for instance, that ‘the environment has no boundaries’, so an accident in one ‘body’ can easily harm another, or many others.

Box 1.2 Fractals

Fractals are irregular shapes featuring the special property of recursive ‘self-similarity’, so that each of their parts is – at least approximately – a reduced-size copy of the whole shape. This makes fractals appear similar at all levels of magnification. However, not all self-similar objects are fractals – for instance, the straight line is self-similar, as all its parts are equal to the whole, but is not an irregular shape. Irregular coastlines and snowflakes are natural objects that resemble fractals.

The optical metaphor

Information per se is quite abstract, but it comes to us through our five senses. Of all these senses, vision seems to be the most ‘trustable’ (as expressions like ‘we must see this to believe it’ indicate), and perhaps conveys the ‘richest’ information – perhaps richer or more useful than sound, touch, smell, or taste. Thus, almost by habit, culture or intuition, we perceive, describe, and shape space with vision as our principal guidance, even though at times we know it is not safe to do so – for instance, a beautiful beach, which is also noisy and/or foul-smelling, is probably overall disagreeable.

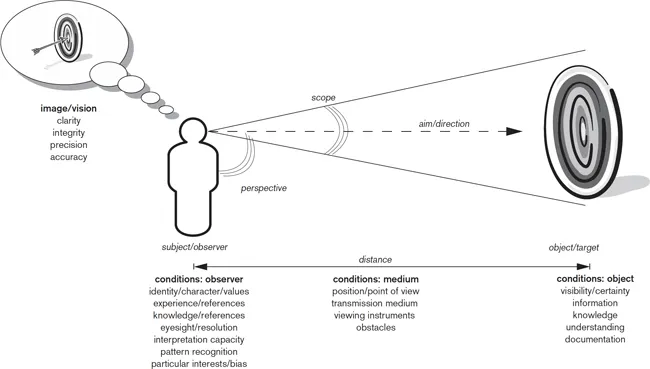

Besides being dominant in the communication of ‘real’ information about space, human vision also has a strong metaphoric presence in the way we receive and store information. For instance, we use the term ‘vision’ for our mental reconstruction of reality, or the conception of a future desired state. This optical metaphor extends to terms such as ‘target’, to identify the object of our interest, ‘aim’ to denote the direction of our concern or thinking (towards that target), and ‘scope’ to denote the amount of information we wish to include. Such expressions are ubiquitous in spatial planning, and even tend to be major references – for instance, in the case of ‘vision’.

The use of metaphors from optics into planning presupposes that we are quite comfortable with the physics and biology of vision – and, a little more generally, of visual cognition, regarding the process of acquiring knowledge through vision. If this is true, then we are aware of what can interfere with obtaining a ‘clear picture’, or the ‘full picture’, and we know how to adjust it – for instance, distance, the optic medium, distortion of information, etc. Spatial planners are likely to be familiar with optics, but the diversity of orientations (or preparations) for the profession indicates that not everyone is likely to be familiar with that. Those with less physics instruction – for instance, from the social sciences – will probably have to make an effort to use the optics metaphors appropriately, with scientific rigour. Not doing so may result in confusions and misconceptions, since a corrupt ‘original’ (optics) cannot be expected to produce a trustable ‘derivative’ (spatial planning).

Figure 1.1

Key concepts in spatial planning are often expressed through metaphors from optics

The ‘tools of the trade’ metaphor

Before spatial planners can produce results ‘on the ground’, they work with mental models (such as visions), and often with official documents such as maps, reports, and statements – in which we can include ‘plans’ and ‘policies’. Such artefacts are to be contrasted with – but are still related to – the physical objects of interest to the planners, such as the natural, built, or mixed spaces they aim to modify. It is widely accepted to use technical or artistic metaphors such as planning ‘instruments’ or ‘tools’ to designate the sets of plans and policies ‘crafted’ by planners, or for the purposes of planning – perhaps revealing some aspects of the technical nature of the work. To accompany the spirit of these metaphors, in this book we aim to develop certain competences – or skills – for the sake of good ‘craftsmanship’ that will help produce worthy instruments.

Box 1.3 Technē (τέχνη)

The word τέχνη (in Greek), which is the major component of the terms ‘technique’, ‘technical’, and ‘technology’, has an interesting gamut of interpretations:

(a) τέχνη is mastering the materials and the instruments, which indicates craftsmanship; this requires skill in making things by hand (which is ‘manufacturing’, if we use Latin components), and is expressed by the term ‘technical’;

(b) τέχνη is producing for the senses, which requires skill in making things by mind; this points to the direction of the ‘fine arts’;

(c) τέχνη ‘with a twist’ is artifice – a cunning plan, like how Odysseus devised the Trojan Horse, or his escape from the Cyclops’ cave;

(d) τέχνη is the missing grammatical element from most adjectives that we now use as nouns, and which denotes a skill – for instance, mathematics (mathematic art), or didactics (didactic art).

Here we can make the first reflection about the role of the planners. If we continue the metaphor of the planners as ‘craftsmen’ (and women) of planning instruments, we realise that ‘clients’ place orders for ‘instruments for the management of spatial development’ – for instance, politicians in the name of the community. This craftsman–client model hints to the separation of technical–political jurisdictions, which has been an issue of debate along the years (Breheny and Hooper 1985; Baum 1983).

Box 1.4 Politics

Interestingly, politics is yet another adjective that we use as a noun, and whose ‘missing part’ is τέχνη (art). In its original meaning, politics is the art of dealing with the issues of the city (πόλις in Greek). This was synonym of the (then) metaphoric term ‘governance’ – from Greek κυβερνείν, ‘to steer’ or ‘direct’, as in a boat.

In contemporary use, ‘political’ tends to indicate something that is not ‘technical’, with the former being placed in the domain of debate, and the latter in the domain of practical issues – that is, concerned with the actual doing something rather than with ideas. Over the years, though, ‘political’ sometimes indicates an ‘abuse of power’, from a cunning ‘political manoeuvre’ to the more serious ‘coup d’état’ (French for ‘blow of state’).

The journey metaphor

Spatial planners are expected to be comfortable with space, describing it, drawi...