![]()

1.1 BIOECONOMY AND CIRCULAR BIOECONOMY

This book is intended to accelerate the emergence of the bioeconomy defined as those parts of the economy that use biological renewable resources to produce food, feed, materials, chemicals, and energy. It will demonstrate why the bioeconomy is crucial for the future generations.

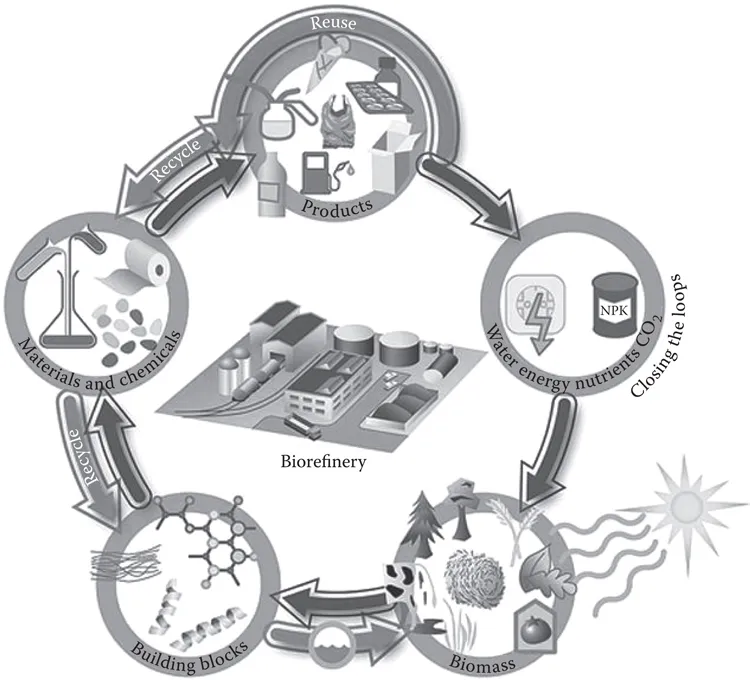

The bioeconomy is circular by nature because carbon is sequestered from the atmosphere by plants. After uses and reuses of products (or molecules) made from those plants, the carbon is cycled back as soil carbon or as atmospheric carbon once again (Figure 1.1).1

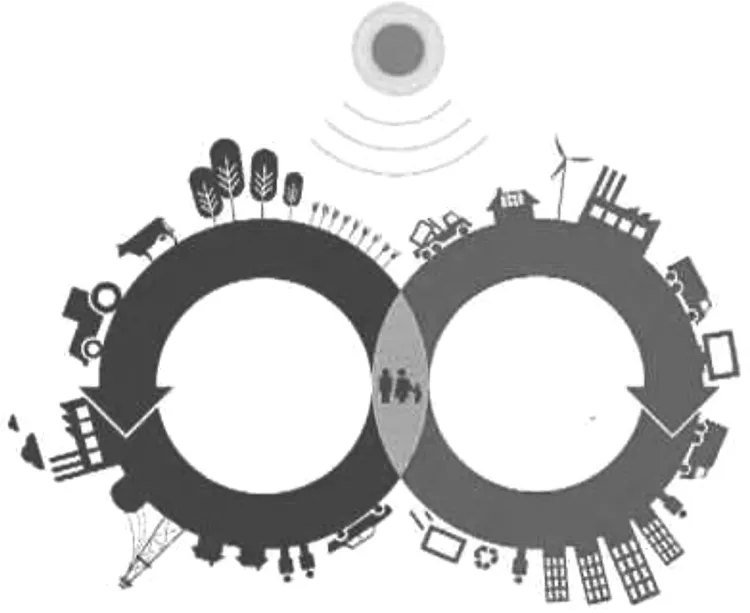

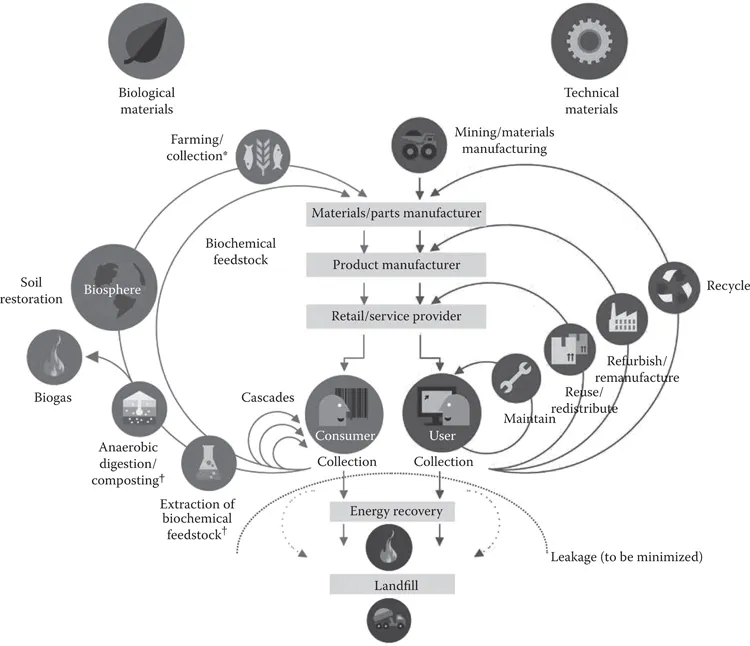

The circular economy focuses mainly on the efficient use of finite resources and ensures that those are used and recycled as long as possible.2 The bioeconomy integrates the sustainable production and conversion of renewable resources. It is the renewable part of the circular economy. The principle of the circular economy is thus complementary to the renewable character of the bioeconomy and must facilitate the recycling of carbonaceous molecules after efficient uses (Figures 1.2 and 1.3). The huge benefits from the circular economy will be truly felt if the bioeconomy—the renewable part of the circular economy concept—is made to play its important and growing role.

FIGURE 1.1 Bioeconomy as part of the circular economy. (Courtesy of Patrick van Leeuwen; Reproduced from Bio-based Industries Consortium, Bioeconomy: Circular by Nature, http://biconsortium.eu/news/bioeconomy-circular-nature, 2015. With permission.)

FIGURE 1.2 The left circle is the bioeconomy; the right circle is the technical economy. (Courtesy of Loes Deutekom; Reproduced from Partners4Innovation, Towards a Biobased and Circular Economy, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ibJsOQdeoc, 2013. With permission.)

FIGURE 1.3 Inspired by living systems, the circular economy concept is built around optimizing an entire system of resource or material flows. Like biological materials, technical materials can be part of a cycle built around reuse, remanufacture, and recycling. A circular economy advocates a shift away from the consumption of products to services. (Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. Nat. Clim. Change, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 3, 180, copyright 2013.)

In the core of this economy are the biorefineries that sustainably transform biomass into food, feed, chemicals, materials, and bioenergy (fuels, heat, and power) generally through combination of plant chemistry and biotechnologies.

Lignocellulosic biomass consists of three major components—cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin—which form the plant cell wall. Although the cell walls of plants vary in both composition and organization, they are all constructed using a structural principle common to all fiber composites.5 How the cell wall is biosynthesized is not yet completely understood today.

Historically, cellulose was investigated the first, about 20 years ago, which resulted in bioethanol fuel. Research on hemicelluloses followed resulting in valorization of 5 carbon (C5) sugars. Investigation on lignin is starting now, with the growing understanding that the whole plant should be valorized and not only its cellulose and hemicelluloses fractions.

1.2 BIOECONOMY

1.2.1 DEFINITION AND STAKES

Over the coming decades, the world will witness increased competition for limited and finite natural resources. A growing global population will need a safe and secure food supply. Climate change will have an impact on primary production systems such as agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and aquaculture.6

A transition is needed toward an optimal use of renewable biological resources. We must move toward sustainable primary production and processing systems that can optimally produce food, fiber, and other biobased products with fewer inputs, less environmental impact, and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The optimal production refers to modern concepts such as Functional Economy. The Functional Economy is a concept that describes new economic dynamics based on providing solutions including the use of equipment and services from a perspective that reduces the mobilization of material resources while increasing the servicial value (the useful effects) of the solution.7 The model proposes to exchange the material goods by functional goods.

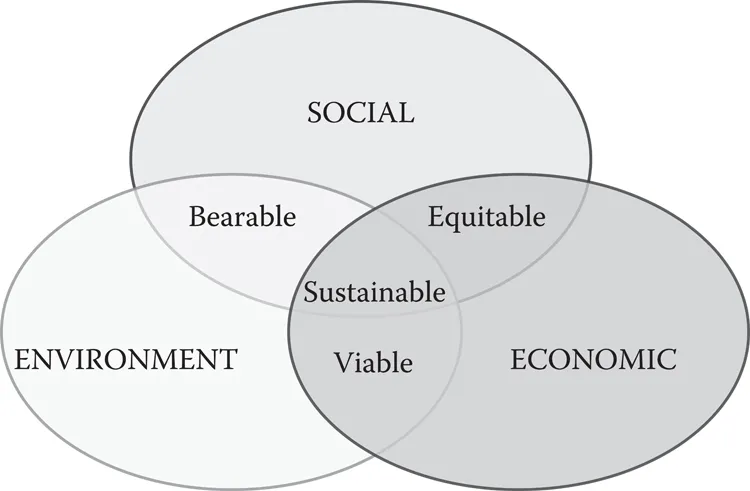

In 1989, the World Commission on Environment and Development—created by the United Nations and chaired by the Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland—has defined sustainable development as “development which meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”8 Sustainability includes three pillars: environment, social, and economic. That definition explains without ambiguity that economic and social well-being cannot coexist with measures that impact over the environment (Figure 1.4).

According to the EU definition, the bioeconomy encompasses the sustainable production of renewable biological resources and their conversion into food, feed, biobased products, and bioenergy.11 It includes agriculture, forestry, fisheries, food and pulp, and paper production, as well as parts of chemical, biotechnological, and energy industries. Its sectors and industries have a strong innovation potential due to an increasing demand for its goods (food, energy, other biobased products) and to their use of a wide range of sciences (from agronomy to process engineering or materials sciences) and industrial technologies, along with local and tacit knowledge.

FIGURE 1.4 The three pillars of sustainability. (Adapted from Green Planet Ethics, http://greenplanetethics.com/wordpress/sustainable-development-can-we-balance-sustainable-development-with-growth-to-help-protect-us-from-ourselves; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sustainable_development.svg.)

TABLE 1.1

The Bio...