- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

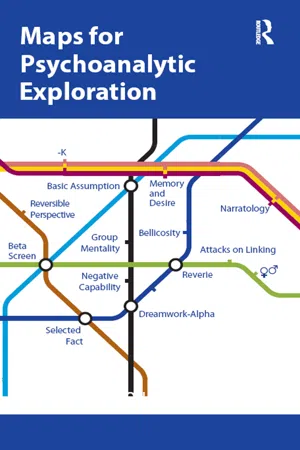

Maps for Psychoanalytic Exploration

About this book

Maps for Psychoanalytic Exploration brings together the author's main works, until now published only in Italian. They are made available to a wider readership in this volume through a translation into English by Shaun Whiteside, supported by the generosity of the members of the Melanie Klein Trust. In these chapters the author explores important implications of her father's ideas at different levels of psychic and social organisation. Her writing is very clear and, as Dr Anna Bauzzi, the Editor of the Italian edition, writes in her Introduction, the quality of it makes many of Bion's ideas more accessible, without any reduction of their complexity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Why we can’t call ourselves Bionians (1987): notes on the life and work of W. R. Bion

Bion has the reputation of being a difficult writer—abstruse, tough, and, I would add, not easily reducible to a “short summary”. In fact, it is practically impossible to speak of his work overall without misrepresenting it: so it seems to me that the simplest, and perhaps the wisest, approach is that of identifying at least some of the elements that make this work such uneasy reading, not least for the psychoanalysts who are the audience the Bion specifically had in mind as the addressees of his books.

To start with, we may make a first, crude (and falsifying) distinction between form and content: then, might difficulties of reading have arisen only because his style of writing was intentionally so concentrated as to appear practically spare? Or is there some difficulty inherent in the nature of the object under discussion?

I think that both these factors probably have a role to play, and I maintain that it is worth looking at them in greater detail, before moving on to some considerations of Bion’s life in the light of his intellectual journey. From the first work published by Bion with his own signature—hence omitting articles in scientific journals that were published anonymously—which is a chapter in the contribution to a book edited by Emanuel Miller into shell-shock victims, published in 1940, we see two aspects of Bion’s writing which will remain throughout the whole span of his creative life and which give, from the start, an idea of the stylistic difficulties of his work, that is, a need to write in a clear and concise way, and the preoccupation with the emotional effect that his words have been able to produce in the reader. The text of Bion’s chapter begins as follows:

The war of nerves is nothing new as a fact of human experience; what is new is that its existence has been recognised under an almost medical title. The subject is too vast and too theoretical for a book which is intended to be of immediate use, and this chapter will therefore be limited to the consideration of a few points that may be helpful in understanding practical suggestions made later. If the style is dogmatic, this may be taken as a symptom of the need for compression and not as a claim to omniscience. (Bion, 1940, p. 5)1

Without making any other comments, I should like to juxtapose with this quotation a phrase from a paper by Nissim Momigliano (1981) in which she describes her own reaction to a paper by Bion from 19672

… the unusual style, absolutely unexpected for a scientific work. This author, almost unknown to me at the time, did not propose, but proclaimed in a curt, crisp and almost hermetic way … (Momigliano, 1981, p. 546)

It may be said that a certain essentiality of writing, which obliged Bion to make quite a recherché and precise choice of terminology, was one of the constants in his work, and I think in the extreme economy of Bion’s writing we may identify one of the reasons why it is so difficult to “sum up” Bion—is already a “brief summary” in itself. He seemed to write according to a sculptural rule of Michelangelo’s, that of “taking away”: having always set himself the problem of how to write to be better understood, Bion “lent an ear”, so to speak, to the possible reactions of his readers, to the emotional effect that his words could evoke. It is certainly no coincidence that in this short paper from 1940 there already appears a fragment of Tacitus in which the Roman historian describes the emotional effect on the barbarian hordes of the war chants of their bards, and the use made of the observations of the emotional reactions of the mass of warriors to make a decision about what to do. This attention devoted to the emotional reactions of the reader, which is naturally interwoven with the accurate choice of terminology, developed more and more with the passing years until it became the pressing need to write about psychoanalysis in such a way as to make the object of the analytic discourse present in all its concision.

In the last trilogy (A Memoir of the Future, 1975–1979), we can clearly see how for Bion the object of analytic discourse takes in not only the thoughts expressed, for example, in a session, but also the emotional climate created, and which underpins the formation of the thoughts, which are then expressed verbally. Certainly the desired stimulation of the reader’s emotions, which are then “discussed” with him—hence the dialogue form of certain passages in these books—is one of the factors that make these last texts very unsettling to read. Until now, we have identified two elements that make it very difficult to read Bion calmly, and also to talk about his work over all—the essential writing and the evocation of emotions. This leads us to the second aspect of the problem—is it possible that there is something inherent in the very nature of the universe of discourse that Bion has chosen that makes it impossible to “place” him? And which also has a profoundly unsettling effect on his readers? I think so: I think the universe we are dealing with is a post-big-bang universe—a universe in expansion after the catastrophic changes that have occurred in various waves through the work of Freud, Klein, and Bion himself. We can no longer think in terms of a closed system; as Bion asserts a number of times, we must not think of psychoanalysis as a closed system, as a container of psychoanalytic knowledge, but rather as a spatial probe. Our problem is that we can only follow the probe, we can’t know where it will go—we are always on the brink of the unknown, and this is an extremely disagreeable situation. We might say that the “mystic” Bion has “burst” the previous bounds of the analytic universe: so what happens next, and how do we go on practising psychoanalysis today?

Bion’s advice to eliminate Memory and Desire, advice that has given rise to a great variety of misunderstandings,3 is revealed not to be an esoteric asceticism, but something like a practical piece of advice very firmly rooted in professional experience; following this technique, we can see moment by moment the evolution of the session, the subtle movements and displacements of forces which “are” the psychoanalytic session.4 It turns the experience psychoanalysis for the analyst—and, I think, also for the patients—something absolutely extraordinary and unique; certainly the initial price that is paid when we try to put this particular mental discipline into practice, which has a curious aesthetic quality, is to feel extremely lost and unsupported—where are the psychiatric nosology, the structures and defences, the ego, the self? Where can I anchor myself? The answer seems to be nowhere—if you anchor yourself, you stop travelling.

This mental attitude on the part of the analyst, which at first glance seems to be a long way away from Freud, is nothing but the evolution of free-floating attention through the maternal reverie, and is an emanation of a meta-psychological concept that underpins all of Bion’s work, that of truth, in a meaning, however, very different from the more familiar religious one, in which the Truth is considered Absolute and Immutable. For Bion, on the other hand, the truth is in a continuous process of becoming, in evolution.—it is not a progressive approach towards the truth on our part, but the evolution of the truth itself.5 This concept, in itself simple to set out, turns out to contrast starkly with the usual way of conceiving the truth. It also seems to be quite a difficult concept to link to practical life—not only in psychoanalysis, in sessions, where its use, working from this point of view, is often accompanied by an effect of “holy terror”, but which also asks us how the perception of truth as a process can change the individual’s way of life and daily thought—or perhaps it makes no difference?

I think, on the other hand, that it does make a difference, in an obvious way. Of course, it is a commonplace that the scientist is in constant search of the truth—but this is not the point. If I look at the development of Bion’s work, and his life choices after the First World War, bearing in mind the concept of “ever-evolving truth”, I think I identify a certain coherence which bears out the sense of restlessness—and which corresponds, incidentally, to Fornari’s critique concerning the “break in continuity” that Bion often mentions in relation to the transformations in K.6 My impression of Bion, as a person, was of someone who lived every intellectual experience so intensely as to get to the bottom of it, and to touch the boundaries of the mental space that that experience could give: at this point, simply, those boundaries which had been a goal became an obstacle to be overcome, a jetty to set off from for other shores, in a way similar to those in which the individual’s first defences, being functional and useful, become an obstacle to subsequent growth: but Bion did not allow himself to be obstructed for long—he had a great sense of freedom.

In this light we may see how the experience of working with a great surgeon, turns into an interest in work that its not surgical at all, on the herd instincts in peace and war, how these interests then led Bion to undertake a course of psychotherapy with Hadfield at the Tavistock, to perform psychotherapy himself, to deal not only with formal groups (not intended to treat the individual in the group—publicly—or to discover the origins of the unease of the individual in the group, but rather to show that individual neuroses are a problem for the group, and that the group must learn to manage the disorder created by its own sick members) but also social aspects and social duties of the specialist in psychic matters—it is highly illuminating with regard to the work “Psychiatry at a time of crisis” along with the chapter of Miller’s book quoted above.

In 1937 it appears that Bion had exhausted the possibilities of psychotherapy and began a course of analysis with Rickman: his first impact on the training committee of the British Society seems both like a good illustration of his own need to make things clear and the capacity of the British Society to “make room” for a personality who was perhaps, even then, a little awkward, and not at all inclined to compromise. On 3 May 1938, the name of Bion appears in the minutes of the training committee because he was not willing to sign the commitment not to use the title of psychoanalyst, or that of not working as a psychotherapist if he were accepted as a candidate. On 5 July the Committee was informed the Bion had agreed to reformulate this commitment after a discussion with Glover, and had promised that he would not go on working for the Institute of Medical Psychology7 after completing his analytic training. On 25 October Rickman informed the Training Committee that Bion had begun analysis with him, and the decision was made to treat Bion as if had been accepted as a candidate.

In reality, the course of Bion’s training was not easy, not just because of his previous relations with the Tavistock, which were very unpopular, but also because he had to interrupt his analysis with Rickman, because of the war, and because they found themselves working together in Northfield, he was unable to resume it. In spite of the advice of the teaching committee to begin an analysis with Winnicott, Bion preferred to start with Klein in 1945. He was elected Associate Member in 1948 and a Member in 1951. Bion’s move to California in 1968 responded not only to his need to live in a climate more tolerable than the one in London, but also the need to open up new mental spaces, of find new stimuli.

I would now like to turn my attention to Bion’s work, to see if we can follow the evolution—perhaps only of a single concept—through the phases of conception, birth, development and abandonment, when the concept itself had become too tight and rigid a container for its author’s thought; perhaps the concept that left a more visible trace is that of the grid.

This story also begins in the 1943 paper “Intra-group tensions in therapy” (originally published in The Lancet, it was then published as the first chapter of Experiences in Groups, 1961). Bion was trying to explain how he visualised the future organisation of the training wing of Northfield, a military hospital where Bion and Rickman had the task of managing patients “with nervous illnesses”. I quote Bion’s visualisation of “… the projected organisation of the training wing as if it were a framework enclosed within transparent walls. Into this space the patient would be admitted at one point, and the activities within that space would be so organised that he could move freely in any direction according to the resultant of his conflicting impulses. His movements as far as possible were not to be distorted by outside interference. As a result his behaviour could be trusted to give a fair indication of his effective will and aims, as opposed to the aims he himself proclaimed or that the psychiatrist wished him to have.” I think that anyone familiar with the use of the grid to map the patient’s movements during the sessions will recognise its precursor in this brief sketch. The actual grid appeared in 1963, and remained a valid working tool for a number of years.

The short paper “The Grid” dates from 1971, but its importance already seems to be diminishing from “Notes on memory and desire” (1967), and Attention and Interpretation (1970) seems to mark a kind of watershed, in which the rigidity of the grid is gradually abandoned in favour of the richer and more generative concept of ideas concerning the idea of seeking “configurations” in the session and the evolution of O.

We might also wonder on which plane in his strictly personal and family life Bion felt the same freedom of development. I have tried to work out whether there are traces of my memories of Bion, as a father and not as a psychoanalyst, because they might be able to shed some light: an episode immediately came to mind which struck me as entirely normal, even if in retrospective it made me think a great deal about Bion’s ability to contain his own paternal anxieties in favour of other people’s freedom.

I had to leave, having just turned eighteen, for a long period of study in Italy. The day before I left, my father told me he wanted to talk to me in his study. I went into the room: silence—he was writing, perhaps he hadn’t even noticed that I was there. After a while, and without much enthusiasm, because I had expected something paternal in some way—which would have been logical—I said, “I’m here.”

“Oh, yes—I just wanted to say two things to you before you left. Remember to go and see the contemporary paintings in the Pitti Palace as well,” (meaning, don’t forget that Italy, Italian culture, isn’t just a thing of the past, it’s alive and growing “and also, this is for when you get lost.” “This” was a little map of Europe and Asia Minor.)

To conclude, I would like to say that it is probably this quality of mental freedom that made Bion such a disconcerting person, and an academic who could not, by his very nature, “found a school”—we cannot call ourselves Bionians, because that would primarily mean being ourselves, being mentally free of our voyages of discovery—always, however, on the basis of personal iron discipline, because freedom and anarchy are not synonymous.

Notes

1Author’s italics.

2Notes on Memory and Desire (1967) was published in 1969 in Italian, Notas sobra la memoria y el deseo. Revista de Psicoanalisis, XXVI, 3, 679–682 (translated from The Psychoanalytic Forum, 1967, II, 3).

3See, for example, Cremerius (1985, p. 115): “… the others (for example Bion, 1976) say that analysis is aimed at attainment [on the part of the patient] of a state ‘free of memory, desire or understanding’.” The italicised text, which gives the complete sense of Creme-rius’s phrase, is the author’s.

4Very illuminating with regard to the work of Betty Joseph and “psychic change”.

5See Attention and Interpretation, Chapter Three.

6See Fornari (1981, p. 655).

7This was the name of the Tavistock Clinic before the war. I am indebted to Miss P. King for this information.

CHAPTER TWO

Psychoana...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER ONE Why we can’t call ourselves Bionians (1987): notes on the life and work of W. R. Bion

- CHAPTER TWO Psychoanalysis is a “poppy field” (1988): “vision” in analysis; a divertissement about the vertex

- CHAPTER THREE Ps⇌D (1981)

- CHAPTER FOUR The role of the group with regard to the “unthinkability” of nuclear war (1987)

- CHAPTER FIVE On “non-therapeutic” groups (1989): the use of the “task” as a defence against anxieties

- CHAPTER SIX Warum Krieg? (1990): the Freud-Einstein correspondence in the context of psychoanalytic social thought

- CHAPTER SEVEN Aggressiveness-bellicosity and belligerence (1991): passing from the mental state to active behaviour

- CHAPTER EIGHT The creation of mental models (1992): basic and ephemeral models

- CHAPTER NINE Experiences in Groups revisited (1992)

- CHAPTER TEN Some notes on the theories of structure and mental functioning underlying A Memoir of the Future by W. R. Bion (1993): festschrift for Francesco Corrao

- CHAPTER ELEVEN From free-floating attention to dream-work-a (1993)

- CHAPTER TWELVE Inside and outside the transference: more versions of the same story (1995)—or: history versus geography?

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN The concept of the individual in the work of W. R. Bion, with particular reference to Cogitations (1996)

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN The two sides of the caesura (1996)

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN Bion and the group: knowing, learning, teaching (1996)

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN Bion’s contribution to psychoanalysis (1996)

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Bion: a Freudian innovator (1997)

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Dreams (1998)

- CHAPTER NINETEEN From formless to form (1998)

- CHAPTER TWENTY Laying low and saying (almost) nothing (1998)

- REFERENCES FURTHER READING

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Maps for Psychoanalytic Exploration by Parthenope Bion Talamo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.