eBook - ePub

Transitions to Better Lives

Offender Readiness and Rehabilitation

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Transitions to Better Lives

Offender Readiness and Rehabilitation

About this book

Transitions to Better Lives aims to describe, collate, and summarize a body of recent research – both theoretical and empirical – that explores the issue of treatment readiness in offender programming. It is divided into three sections:

- part one unpacks a model of treatment readiness, and explains how it has been operationalized

- part two discusses how the construct has been applied to the treatment of different offender groups

- part three iscusses some of the practice approaches that have been identified as holding promise in addressing low levels of offender readiness are discussed.

Included within each section are contributions from a number of authors whose work, in recent years, has stimulated discussion and helped to inform practice in offender rehabilitation.

This book is an ideal resource for those who study within the field of criminology, or who work in the criminal justice system, and have an interest in the delivery of rehabilitation and reintegration programmes for offenders. This includes psychologists, social workers, probation and parole officers, and prison officers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Transitions to Better Lives by Andrew Day,Sharon Casey,Tony Ward,Kevin Howells,James Vess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

What is Treatment Readiness?

Chapter 1

The Multifactor Offender Readiness Model

These are particularly challenging times for researchers and practitioners who seek to work with offenders in ways that will assist them to live better lives. A range of different perspectives currently inform this work, from those that emphasise the rights of victims and communities to those that emphasise the rights of individual offenders. In many parts of the world, more and more people are being imprisoned and for longer periods of time. Communities are becoming more risk aversive and punitive in their attitudes towards offenders and there would appear to be a growing determination to make individuals pay severely for transgressions against the state. At the same time significant effort is put into rehabilitating offenders and helping them to plan for a successful reintegration back into society. Indeed, the last twenty or so years have seen significant investment in the development and delivery of offender rehabilitation programmes across the western world, in both prison and community correctional (probation and parole) settings, and support for rehabilitative ideals is perhaps now more clearly enshrined in public policy than perhaps at any time in the past. That is not to say, however, that the value of offender rehabilitation is universally recognised, and it is in this context that interest in issues such as human rights, offender dignity, and the values of offender rehabilitation has grown (see Ward and Birgden 2007; Ward and Maruna 2007).

The socio-political context in which any work with offenders takes place ensures that attempts to reintegrate or rehabilitate offenders will almost certainly come under a high level of scrutiny, both public and professional. It is now more important than ever that rehabilitation providers can demonstrate that their efforts are effective in reducing rates of reoffending or, at the very least, consistent with those practices that have been shown to be effective in other settings. Most correctional agencies have now developed accreditation and quality assurance systems designed specifically to ensure that the programmes offered meet basic standards of good practice. There are thousands of controlled outcome studies from which to determine the types of intervention that are likely to be effective (Hollin 2000), the results of which, when aggregated, offer consistent and persuasive evidence that offender rehabilitation programmes can, and do, have a positive effect on reducing recidivism. Furthermore, it is clear that these reductions are likely to be of a magnitude that is socially significant. It has also become apparent that programmes that adhere to certain principles are likely to be even more successful in reducing recidivism (Andrews and Dowden 2007). It is this knowledge that has led to the development of a model of offender management commonly known as the ‘what works’ or ‘risk—needs—responsivity’ (or RNR) approach, based largely on the seminal work of Don Andrews and James Bonta.

The RNR approach centres around the application of a number of core principles to offender rehabilitation (primarily the risk, needs, and responsivity principles), each of which seeks to identify the type of person who might be considered suitable for rehabilitation initiatives. Perhaps most progress here has been made in the area of risk assessment, with recent years seeing the development and validation of a wide range of specialist tools designed to help identify those who are most likely to reoffend. The logic is compelling — if the goal of intervention is to reduce recidivism, then effort should be invested in working with those who are the most likely to reoffend, rather than those who probably will not. It is possible to meaningfully categorise offenders into different risk brackets using a relatively small set of variables (such as the age at first offence or the number of previous offences). A focus of current work in this area is on the identification and assessment of those risk factors that have the potential to change over time. These ‘dynamic’ risk factors, or what have become known as ‘criminogenic needs’ (see Webster et al. 1997), are particularly important in determining treatment targets (that is those areas of functioning that might be addressed within offender rehabilitation programmes). In comparison, the third major tenet of the RNR approach — responsivity — has been somewhat neglected. This term is commonly used to refer to those characteristics of individual offenders (such as motivation to change) that are likely to influence how much they are able to benefit from a particular programme.

In many respects, the RNR approach has revolutionised correctional practice. It has promoted the idea of community safety as the primary driver behind correctional case management, and given offender rehabilitation programmes a central role in the sentence planning process. The approach has had a major impact on practice in relation to offender assessment and the selection of appropriate candidates for intervention around the western world. It has, however, had less influence on the actual practice of offender rehabilitation (see Andrews 2006; Bonta et al. 2008), and significant gaps in knowledge remain (Andrews and Dowden 2007). Critics of the RNR model have, in a range of different ways, drawn attention to how the model struggles to inform the process of programme delivery, and how psychological and behaviour change takes place. This may be, in part, because the RNR model was developed as an approach to offender management rather than psychological therapy. It may also perhaps relate to difficulties in the way in which some of the key terms (notably risk and needs) have been conceptualised, and in particular how the overarching focus on risk can be experienced as demotivating for individual participants in rehabilitation programmes, ultimately contributing towards high rates of programme attrition and a lack of rehabilitative success (Thomas-Peter 2006; Ward and Stewart 2003). While the notion that offender rehabilitation is something that can be done to someone, possibly even without their consent, has appeal, it is also therapeutically naive. The gains made in the area of offender assessment and selection have not, in our view, been matched by progress in the area of offender treatment, where concerns are commonly expressed about issues of offender motivation and engagement in behaviour change, therapist skill and training, programme integrity, and the social climate of institutions in which interventions are delivered.

Perhaps nowhere are these issues more apparent than in the areas of treatment readiness and responsivity. It is our contention that work in this area has been hampered by a lack of conceptual clarity about the construct of responsivity, how it might be operationalised, and how it might be reliably assessed. In this book, we explore the idea that even greater reductions in recidivism than those demonstrated in programmes that adhere to the evidence-based principles of risk and needs can be made when programmes are able to be responsive to individual needs. We discuss the meaning and nature of the term ‘treatment readiness’ and how this might inform the rehabilitative process. Readiness is proposed as an overarching term that encompasses both the internal components of responsivity (offender motivation, problem awareness, emotional capacity to engage with psychological treatment, goals, and personal identity), as well as those external components that may be specific to the environment in which treatment is commonly offered.

Our interest in the notion of treatment readiness arose out of work in which we examined the effects of anger management programmes offered to offenders (Howells et al. 2005; Heseltine et al. 2009). These evaluations suggested that anger management training, at least of the type commonly offered in Australian prisons at the time, was unlikely to be particularly effective in bringing about behavioural change — in this context this referred to physical aggression and violent behaviour of a criminal nature. At the time, prison administrations across Australia dedicated considerable energy and resources to the development and delivery of anger management programmes to violent offenders, and so these apparently weak treatment effects required some explanation. A number of hypotheses were proposed, including those relating to the selection of appropriate candidates, the matching of the intensity of the intervention to the level of risk and need, and the extent to which those who are imprisoned for violent offending might be considered to be ready for treatment. In a subsequent paper, Howells and Day (2003) developed the notion of treatment readiness by identifying seven impediments that potentially inhibited the effective treatment of offenders presenting with anger problems (see Table 1.1).

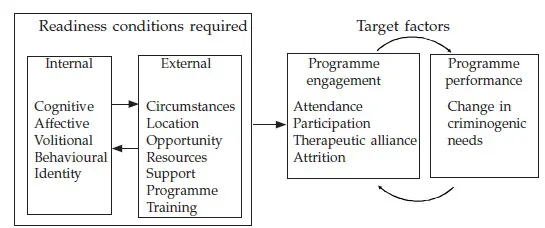

This work was subsequently elaborated into a more general model of readiness which was then applied to all forms of offender rehabilitation programming (Ward et al. 2004b).The Multifactor Offender Readiness Model (MORM) proposed that impediments or barriers to offender treatment can reside within the person, the context, or within the therapy or therapeutic environment. The following definition of treatment readiness was put forward: the presence of characteristics (states or dispositions) within either the client or the therapeutic situation, which are likely to promote engagement in therapy and which, thereby, are likely to enhance therapeutic change. According to this definition, readiness to change persistent offending behaviour requires the existence of certain internal and external conditions within a particular context (see Figure 1.1). Offenders who are ready to enter a specific treatment programme are thus viewed as possessing a number of core psychological features that enable them to function well in a particular rehabilitation programme at a particular time.

Table 1.1 Impediments to readiness for anger management

| Number | Description |

| 1 | The complexity of the cases presenting with anger problems. This includes the coexistence of mental disorders with aggressive behaviour. |

| 2 | The setting in which anger management is conducted. |

| 3 | Existing client inferences about their anger problem.For example, inferences indicating that the anger was viewed as appropriate and justified. |

| 4 | The impact of coerced or mandatory treatment. |

| 5 | The inadequate analysis of context of personal goals within which the anger problem occurs.It is possible that the expression of anger could increase the likelihood that important personal goals are achieved. |

| 6 | Ethnic and cultural differences. |

| 7 | Gender differences in the experience and expression of anger. |

Source: Adapted from Howells and Day (2003).

Individual or person readiness factors are cognitive (beliefs, cognitive strategies), affective (emotions), volitional (goals, wants, or desires), and behavioural (skills and competencies). The contextual readiness factors relate to circumstances in which programmes are offered (mandated vs voluntary, offender type), their location (prison, community), and the opportunity to participate (availability of programmes), as well as the level of interpersonal support that exists (availability of individuals who wish the offender well and would like to see him or her succeed), and the availability of adequate resources (quality of programme, availability of trained and qualified therapist, appropriate culture). It is suggested that these personal and contextual factors combine to determine the likelihood that a person will be ready to benefit from a treatment programme. Those who are treatment ready will engage better in treatment, and this will be observably evident from their rates of attendance, participation, and programme completion. Assuming that programmes are appropriately designed and delivered, and they target criminogenic need, higher levels of engagement are considered likely to lead to reductions in levels of criminogenic need and a consequent reduction in risk level. The model thus incorporates whether or not a person is ready to change his or her behaviour (in the general sense); to eliminate a specific problem; to eliminate a specific problem by virtue of a specific method (such as cognitive behavioural therapy); and, finally,

Figure 1.1 Original model of offender treatment readiness

to eliminate a specific problem by virtue of a specific method at a specific time.

To be treatment ready, offenders must not only recognise that their offending is problematic, but also make a decision to seek help from others. This implies a belief that they are unable to desist from offending unaided. Once the offender makes a genuine commitment not to reoffend, he or she may then be taught the relevant skills and strategies in treatment to help achieve this goal. The decision to seek help may also be affected by factors such as which services are available, attitudes or beliefs about those services, beliefs about the importance of privacy and autonomy, or that problems are likely to diminish over time anyway. The extent to which a behaviour or a feeling is defined as a problem will, in part, be determined by cultural rules and norms relating to what is acceptable or appropriate (for example women generally have more positive attitudes towards help-seeking than men: Boldero and Fallon 1995), and in environments where certain types of offending are considered normative, it is unlikely that the individual will see his/her offending as problematic. Other contextual factors, such as poverty, may also influence the decision to recognise a particular behaviour as a problem. Of course, an offender may be ready to work on a particular problem, but not necessarily one that the therapist views as relevant and central to his or her offending; to be treatment ready, both the treatment provider and the offender have to agree on both the goals and the tasks of the treatment.

The MORM was developed in a way that distinguishes between three distinct although related constructs: treatment motivation, responsivity, and readiness. The constructs of motivation and responsivity are conceptualised as somewhat narrower in scope than that of readiness (see Table 1.2). Furthermore, readiness directs us to ask what is required for successful entry into a programme, while the concept of responsivity focuses attention on what it is that can prevent treatment engagement. Ward et al. (2004b) suggest that the responsivity concept has not really developed conceptual coherence and, as such, is often poorly operationalised as a list of relatively independent factors (see Serin 1998). We suggest that treatment readiness may be a better model because of its greater scope, coherence, testability, and utility (fertility).

Our aim in writing this book is to describe, collate, and summarise a body of recent research, both theoretical and empirical, that explores the issue of treatment readiness in offender programming. The book is divided into different sections. In the first, we unpack our model of treatment readiness and how it has been operationalised. Ralph Serin and colleagues also describe their understanding of the notion of treatment readiness (Chapter 2). We then discuss in Part Two how the construct has been applied to the treatment of different offender groups. In Part Three, we discuss some of the practice approaches that have been identified as holding promise in addressing low levels of offender readiness. We have included contributions from a number of authors whose work has stimu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures and tables

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Authors and contributors

- Dedication

- Part One What is Treatment Readiness?

- Part Two Readiness and Offenders

- Part Three Clinical and Therapeutic Approaches to Working with Low Levels of Readiness

- Appendix: Measures of Treatment Readiness

- Selected journal articles

- References

- Index