eBook - ePub

Looking into Later Life

A Psychoanalytic Approach to Depression and Dementia in Old Age

- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Looking into Later Life

A Psychoanalytic Approach to Depression and Dementia in Old Age

About this book

This book belongs to a long tradition at the Tavistock Clinic of work focused on the mental and emotional well-being of the elderly. It applies psychoanalytic thinking to areas that have generally attracted very little sustained attention over the years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Looking into Later Life by Rachael Davenhill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Overview: Past and Present

Chapter 1

Developments in psychoanalytic thinking and in therapeutic attitudes and services

Rachael Davenhill

In the beginning

In 1896, Freud wrote of his father in his final illness “He is. . . steadily shrinking towards. . . a fateful date”. In 1939 the last book Freud read before his own death, according to his personal physician Max Schur, was Balzac’s short story The Incredible Shrinking Skin [La peau de chagrin]. The irony of his choice was not lost on Freud. According to Schur (1972), “When he finished reading it, he told me, as if by chance: ‘It was the right book for me to read, it talks about shrivelling and starvation’.” The skin is the boundary between the inside and the outside of the body, and at the beginning of life and toward the end of the lifespan the skin holds special significance as a repository for both internal and external reality. Early on, when all goes well, the skin of the baby is given privileged significance. It is touched, treasured, smelt, cooed over. Even the baby’s filled nappy can be experienced as a sweet rather than repugnant smell. From the beginning “we inhabit the body and are inhabited by it at all times” (Britton, 1989). The way in which the mother can respond to and contain the pains and pleasures of her infants’ bodily needs will transform how these are experienced in terms of their emotional significance, and it will lead to the integration of the body itself as an internal object in the psyche (Laufer, 2003). However, this response does not often extend to the latter part of the lifespan. What is noticeable again and again in the care of older people is the lack of significance given to the body other than in a purely functional way—it is there to be washed, fed, toileted—but the emotional meaning of each of these tasks is often denuded. The fragility of the older person’s skin can evoke anxiety in the caretaker (for example, a doctor recently expressed his anxieties about resuscitation following repeated traumatic experience of rupturing the older person’s skin and breaking the rib cage in the process). The care of older people is often criticized for only focusing on physical care and not communication, but, of course, physical care is a nonverbal form of communication.

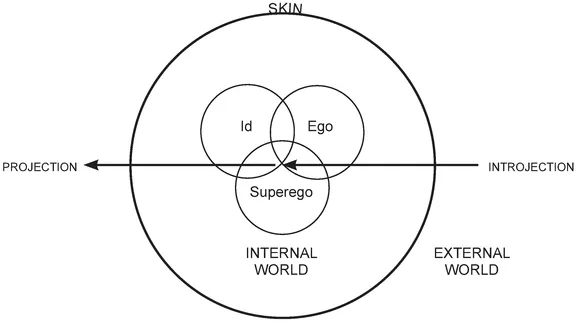

According to Freud, none of us is alone internally. Instead, he suggested, we are inhabited by a company of others—not without, in terms of external reality, but within, in terms of what he called psychic reality. Crudely put, the concept of psychic reality is a little like gathering together the ingredients for a cake and mixing them together—the ingredients start off separate but, once mixed, cannot then be undone in terms of reverting back to the original component parts. He thought there were certain core ingredients that make us who we are. In 1923 he introduced what is referred to as the structural model of the mind, based on psychological forms of internal-object relatedness. This had three main elements. First the id, which Freud thought was completely beyond the access of the conscious mind and formed the basis of the instinctual drives; second the ego, which is the reality sense; and third the superego. The superego is based on an internalized early relationship to the parents and forms the basis of conscience. It can both be benign, in enabling the individual to develop a capacity for making decent judgements in life, or be experienced at times as a harsh, cruel presence, constantly judging the individual in an unremitting and critical way. These structures in the mind develop very early on, and the form they take will vary depending on the infant’s perceptions of his or her relationship with his or her parents, partly real and partly based on unconscious phantasy. Conscious and unconscious perception can vary and change within the individual depending on the prevailing internal state in interaction with the external environment, and providing a basic template for the mapping of future relationships.

Psychic reality does not predetermine what is internal and external, but in working with the person who is older it does give us the freedom to think in our own minds and with them about not just the external event in itself, but also the individual’s subjective experience of the event. It allows in and recognizes the emotional significance of human experience and its qualities, and it underlines the importance of looking at the emotional significance of the event rather than the “facts of the event” alone. Later on in life, memory will be influenced both by the actual event and by the way in which it may have been distorted by the internal meaning bestowed upon it by the individual. Here the cognitive associations and the emotional associations of the event come together and form the unconscious phantasy, the ether that permeates the internal world of every individual. Once the notion of unconscious phantasy is allowed into the picture, a much richer and deeper colour and texturing of understanding can come to the fore for both patient and clinician. According to Caper (1988), it was from “this shifting from the raw, literal event toward the melding of external and internal instincts, that Freud became a psychoanalyst”. Freud’s last paper was Outline of Psycho-Analysis. He wrote sixty-three pages at the age of 82 (immediately after arriving in London following his escape from Nazi-occupied Austria) between July and September 1938, and it was published in 1940. In his editorial comment to the paper, Strachey wrote that “at the age of 82 Freud still possessed an astonishing gift for making a fresh approach to what might have seemed well-worn topics. Nowhere else, perhaps, does his style reach a higher level of succinctness and lucidity. The whole work gives us a sense of freedom in its presentation which is perhaps to be expected in a master’s last account of the ideas of which he was the creator” (Strachey, in Freud, 1940 [1938], p. 143).

The colouring of any external event is influenced by the psychological processes of projection and introjection, processes that operate continuously throughout the lifespan and help to make us who we are. From the beginning the baby needs to feed and defecate in order to survive, and these basic instincts are the template for in-trojection—the capacity to feed or take in—and for projection—the capacity to expel, push out, or get rid of. The tiny baby instinctively moves towards the breast and feeds when hunger is felt, and fills his or her nappy when discomfort is felt, and these physical processes are imbued with psychological resonance for the baby and his or her carer. The way in which the baby learns to navigate, and is helped to navigate, his or her way through complex emotional states such as hate and frustration can powerfully influence the course that psychic development and the capacity for love and reparation can take at future points in life. (Figure 1 is a representation of this process, and in finishing this drawing it struck me that it has a resemblance to an eye—perhaps a psychic eyeball that can, on a good day, perceive the psychic truth of the matter in terms of the capacity to perceive internal and external reality more accurately—one of the key aims of psychoanalytic treatment.)

Figure 1. Illustration of ongoing oscillation between the internal and external worlds

In his 1917 paper on “Mourning and Melancholia” Freud introduced the notion of “identification” and the incorporation of the lost object into the ego in cases of melancholia or what would now be referred to as an abnormal grief reaction. If the relationship with the dead person has been very ambivalent, the work of mourning is much more difficult in that more loving feelings have been overtaken by hatred. Anger is a normal part of mourning, but if this predominates in the long term then forgiveness and more reparative drives are squeezed out while fury and resentment predominate, which can then lead to severe depression. Throughout life we have constant experiences of loss that have to be mourned in order for new developments to take place. Freud pointed out that losses can include loss of, for example, the mother country or loss of an ideal, as well as loss through death. Karl Abraham, a friend and colleague of Freud, disagreed with Freud’s earlier pessimism and in 1919 described the successful analyses of older patients, commenting that “The prognosis in cases even at an advanced age is favourable. . . the unfavourable cases are those which already have a pronounced obsessional neurosis, etc in childhood and who have never attained a state approaching the normal. These. . . are . . . the kind of cases in which psychoanalytic theory can fail even if the patient is young.” Like Freud, he thought that the work of mourning involved establishing in the internal world the person who had been lost externally. Melanie Klein had been analysed by Abraham, and in the development of her thinking she agreed with him that age-specific factors were not central, but that an understanding of the patient’s level of mental functioning was. Klein thought that the foundations for dealing with loss were established very early on in life, with the earliest loss taking place during the weaning period when the baby has to negotiate the transition from a two–person relationship—usually the feeding relationship with the mother as main caretaker—to a three-person relationship incorporating the father as representing the outside world. She thought that two things interacted constantly when the baby was faced by primitive anxieties at points of transition which inevitably stirred anxiety. One was the capacity of the baby to tolerate frustration, which she thought had a constitutional basis; the other was the way in which loss was responded to by the mother or main caretaker, which could support—or not—the way in which the baby traversed feelings of frustration, loss, guilt, and persecution.

Hanna Segal was the first psychoanalyst to give a detailed published account of the analysis of a 74-year-old man, in her vivid description of working with a man who was referred to her following a psychotic breakdown (Segal, 1958). The paper conveys the importance of holding to the analytic framework as a container for understanding the patient’s unconscious anxieties and phantasies with regard to his fear of death and feelings of persecution in relation to his internal objects, which over the course of the treatment dissipated. Segal regarded this case as one of her most successful in that she heard later that her patient was able to die a “good death”. In a recent Preface (in Junkers, 2006), writing in her late eighties, she further commented on this 1958 treatment as follows:

I learned a tremendous amount from this analysis, particularly about the importance of the fear of death. It made me understand the importance of coming to terms with the finiteness of things at any age. It was poignantly put to me by another patient, who suffered from severe mania, and who told me one day that there was nothing more tragic than getting old when you have not matured. I also learned that old people, though they face particular problems having to do with their age, particularly in analysis the humiliation of being dependent on somebody much younger than themselves, are in fact no different from other patients—each has his or her own individual history and problems which become more acute in old age.

At any age—child, adult, or older adult—there can be complications in really accepting some of the basic facts of life. In popular discourse, being taught the “facts of life” usually refers to sex and sex education. However, on a profound and deeper level, as well as sex (including the differences between the sexes and across generations) there is “the recognition of the inevitability of time and ultimately death” (Money-Kyrle, 1971). While the fact of death—or, perhaps more pertinently, the fear of death and the fact of its reality and the finiteness of life—is of universal relevance whatever age or stage of life, it holds a particular poignancy, strength, and urgency as a motivational force for people in the latter part of the lifespan. For many people it may be that, for the very first time, there is a new-found opportunity through psychotherapy or analysis to deal with an aspect of reality that Money-Kyrle thought was extremely difficult to come to terms with and yet remains crucially important—that of the fact of death, the reality of loss, and the need to mourn if the psyche is to live on creatively and as fully as possible in the latter part of each of our individual lives.

Two riddles

Riddle 1

This thing, all things devours;

Birds, beasts, trees, flowers;

Gnaws iron, bites steel;

Grinds hard stones to meal;

Slays king, ruins town;

And beats high mountain down.

Birds, beasts, trees, flowers;

Gnaws iron, bites steel;

Grinds hard stones to meal;

Slays king, ruins town;

And beats high mountain down.

Although this is a book on later life, the riddle is from a children’s book, The Hobbit by Tolkien. In the story, the little hobbit, Bilbo, is being set increasingly difficult riddles to answer by the menacing character of Gollum, culminating in the one above. As Gollum strides towards Bilbo, demanding an answer to the above riddle, Bilbo wanted to shout “Give me more time, give me time!”, but in his panic all that came out was “Time! Time”. To his amazement and relief he discovers that he has indeed come up with the right answer—for “Time” is the correct solution to the riddle. Many of the depressions presenting in old age are precipitated by panic in the face of time, which, like the figure of Gollum, if not recognized and understood can take on an increasingly frightening and persecutory persona. Time is a direct challenge to the “high mountain” in Tolkien’s riddle, in that it challenges the common feeling that life can carry on forever, highlighting the narcissistic traumas inherent in aspects of the ageing process, and the difficulties this can give rise to. In his pioneering work using brief psychodynamic psychotherapy with older patients at the Tavistock clinic in the 1970s and 1980s, Peter Hildebrand emphasized the reality of time as a strong motivating factor for people seeking out and making use of psychotherapeutic treatment in later life, where there are particular tensions surrounding the reality of time passing and of ageing. Whilst these are not problems specific to later life, nonetheless the facts of life brought in through increased age—of increased physical demands on the body, falls, or actual physical illnesses or disability developing; of retirement; of the death of partner, husband, wife, or friends as time goes by—certainly present a challenge as to how the later phase of life may be weathered emotionally.

Dylan Thomas wrote to his dying father, “Do not go gently into that good night, / old age should burn and rave at close of day; / Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” In much of the writing on old age there is an emphasis on integration and acceptance of one’s lot as an outcome of any decent therapy. Increasingly I am not so sure about this. It may be the case that some individuals are constitutionally more at peace with themselves and with life (and, if so, it is unlikely that they would be seeking out treatment) or that the many older people who do not suffer depression are those who have been able to face earlier experiences with a capacity to mourn rather than become depressed. One of the central tasks of therapeutic treatment is to enable the individual to reclaim areas of themselves that in fact they may have done their very best to get rid of, such as the capacity to become aware of and to feel love, hate, pain, grief, rage—and psychoanalytic psychotherapy in old age involves as much a fight as at any other point in the lifespan. Thomas’s poem illustrates the way in which individuals have the opportunity of becoming more fully alive to who they really are and who they are in relationship to others, at both an external and an internal level. In terms of normal ageing, we do not see the bulk of people. This is where, with sufficient internal resources and a supportive external environment, the challenges of later life can be weathered and worn. But it is often where there may be areas unresolved at an internal level from much earlier in life or pressures externally, or usually a combination of the two, that depression may present itself in old age. If things have not gone so well early on in terms of dealing with the first loss—that of the two-person relationship and the exclusive tie to the main caretaker—then inevitably the losses and pressures of old age will leave the individual more vulnerable. In “Do Not Go Gentle”, Dylan Thomas is writing from the perspective of the one about to be left behind—please don’t go, hang on to life, do not leave me for then I will have to work through the painful process of mourning you. And this equally well applies to the person who is older, who actively remains aware of the need to struggle and work through the transitions and losses of old age, where there is no age bar to internal conflict and it cannot be retired from.

Clinical illustration: Mrs A

Mrs A came into her session saying that she was going to bring her camera to take a photograph of me so that she could frame it and pin it to the wall. Following this she went on to say that she wanted to spend the rest of the session discussing an episode she’d written about in her autobiography, even giving the exact page reference on which it was written down. Although the taking of the photograph and the writing seem different, the underlying problem was the same—depression—which she said was due to writer’s block. It transpired that she had been trying to complete the autobiography since her son’s death, finding herself unable to proceed in writing about her life beyond the age she had been when her son had died. She explained that she had started to write her autobiography as she sat next to her teenage son’s bedside thirty-five years previously when he was dying of cancer. I thought the wish to frame me was in part a way of wanting to control me in time, and we were able to explore the way in which she felt pinned in time, unable to move forwards or backwards, something that the perseveration in going over and over one page in the autobiography also seemed to indicate. Mrs A needed to fully mourn her son in order to move onto a new chapter, not of her writing, but of her life. Over the course of the consultation it became more possible to think with her about the way in which both her problem with writing and her wish to frame me in a static way was an unconscious repetition of her difficulty in moving on.

Riddle 2

“What being, with only one voice, has sometimes two feet, sometimes three, sometimes four, and is weakest when it has the most?”

Traversing the lifespan challenges the individual over and again with the oedipal dilemma, which continues to appear and reappear alive and kicking whether 5, 55, or 95 years old. In the myth of Oedipus, Oedipus, fresh from killing (unbeknown to him) his father, Laius, on the road to Thebes, is confronted by the Sphinx, who throttles and devours anyone unable to answer the above riddle which she sets. Oedipus responds with th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- SERIES EDITOR'S PREFACE

- ABOUT THE EDITOR AND CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- Introduction

- PART I Overview: past and present

- PART II Mainly depression

- PART III Observation and consultation

- PART IV Mainly dementia

- REFERENCES

- INDEX