![]()

p.11

PART I

Theoretical Foundations

![]()

p.13

1

ATHLETE REPUTATIONAL CRISES: ONE POINT FOR LINKING

Situational Crisis Communication Theory and Sports Crises

W. Timothy Coombs

As evidenced by this project and other publications, there is a growing interest in applying crisis communication to sports crises. Globally, sports organizations are major businesses involving billions of dollars annually (Billings, Butterworth, & Turman, 2015) and we think of sport as an industry. Granted, sport is a diverse industry covering teams and individuals as well as professional and amateur. Sport has some unique features as an industry that separate it from typical corporations and create unique crisis communication demands. These unique features can influence how we adapt and apply crisis communication theory, developed for typical corporations, to sports crises. In this chapter, I posit that sport as an industry holds important modifiers when applying Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) (Coombs, 2007) to certain types of sports crises. The chapter is divided into three sections. The first section explains the context of crisis communication and the development of SCCT; the second section explores the reputational nature of sports crises through athlete reputational crises (ARC); while the final section considers the application of SCCT to athlete reputational crises.

The Context of Crisis Communication

Crisis communication emerged when developing interest in crisis management became a distinct area of interest for practitioners and researchers in the 1980s. Crisis communication was beneficial to organizations because it helped managers to survive and to recover from operational crises. Operational crises represent actual or potential disruptions to the functioning of a firm. Facility fires, toxic chemical releases, product harm recalls, and weather disruptions to airline traffic are all examples of operational crises. The early definitions of crises emphasize the focus on disruption/potential disruption of operations (e.g., Barton, 2001; Fink, 1986). Risk assessments, crisis plans, and training reflected the focus on operational crisis. A distinguishing feature of operational crises is that they frequently involve a risk to public safety (including employees). Consider how a product harm crisis places customers at risk, while toxic chemical releases pose threats to employees and community members living in close proximity to the facility.

p.14

As Barton (2001) noted, all crises present some reputational threat to a given organization. Other scholars have posited that reputational crises are a unique form of crisis. Booth (2000) argued that reputational crises do not have be event driven but can be the result of the organization being associated with “some other activity, entity, or incident” (p. 197). Sohn and Lariscy (2014) favor an event-based view, specifying that a reputational crisis is problematic because it indicates the organization has violated social norms or values. Thus, we can combine the two to define a reputational crisis as a situation or event where stakeholders perceive the organization has violated important social values and is acting irresponsibly.

Reputational crises involve some specific reputational damage to the organizations and generally lack the immediate concerns over public safety. That does not mean some entities will not be harmed by a reputational crisis but that the damage is limited and unlikely to spread as in an operational crisis. When a top manager is guilty of sexual harassment, there are victims but other stakeholders are no longer at risk when the manager is removed. When a toxic chemical cloud is released, employees are in immediate danger, as are those living in the path of the cloud. Reputational crises generally have a narrower set of victims and potential victims than do operational crises.

There are important differences between operational and reputational crises that affect what constitutes effective crisis communication. Operational crises are primarily event driven with tangible or concrete indicators such as a harmful product or a release of toxic chemicals. Reputational crises can be event driven or perception driven (stakeholders and organizations agree there is a crisis). The indicators for reputational crises can be intangible and abstract, such as concerns over whether or not an action is irresponsible or offensive, or something that a majority of stakeholders would consider inappropriate. Two examples can illustrate the range of concerns.

In 2010, Greenpeace posted a video mocking a Nestlé commercial. This commercial marked the beginning of Greenpeace’s efforts to define Nestlé’s palm oil sourcing as irresponsible. Not all stakeholders know about palm oil or care about its sourcing—there was room for interpretation. Greenpeace initiated a communication campaign to raise awareness and concern over palm oil sourcing by Nestlé. Nestlé hurt itself by trying to suppress Greenpeace’s message, thereby turning a reputational risk (palm oil sourcing) into a reputational crisis (massive negative commentary in social media; Coombs, 2014). In 2016, a social media comment about a racist Red Cross pool safety poster escalated into a reputational crisis. The poster showed right and wrong behaviors at a public pool. All the right behaviors involved children that were white, while most the wrong behaviors showed children that were black; social media sentiment about the Red Cross went from 10 percent to 80 percent negative. Most people who heard about the poster agreed it seemed racist. The palm oil sourcing concern was much more abstract and open to interpretation than the images in the pool poster.

p.15

We can locate a crisis on both operational and reputational continua, as a crisis can have both operational and reputational concerns. Typically, one of the two continua will dominate the crisis frame: how people are interpreting the crisis. The two continua are required to denote the connection between operational and reputational crises. Most of the extant writing on crisis communication derived from crisis management is based on the original notion of operational crises. The plans and warning signs were developed for operational crises, not reputational crises. That is why organizations often have trouble coping with reputational crises and paracrises (common precursors to a reputational crisis that involve the public management of a crisis risk; Coombs & Holladay, 2012). It could also be argued that crisis thinking itself was constrained by the operational emphasis. I would include SCCT’s original writing as a victim of this operational constraint category. While SCCT does recognize some reputational crises, its central tenets reflect an operational focus. SCCT works best for event-driven crises and are defined primarily by the crisis situation.

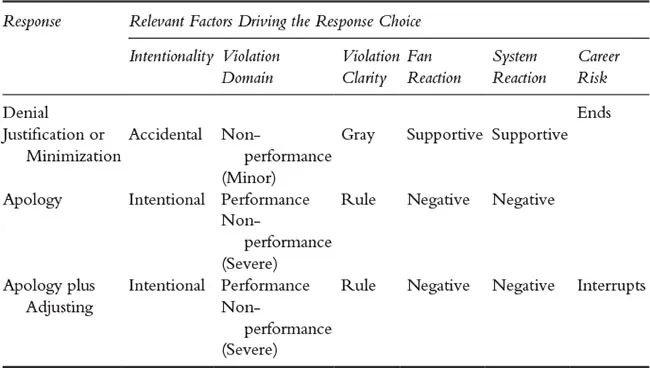

In 2015, SCCT was expanded to address the need to address paracrises and reputational crises. A paracrisis occurs when organizations manage a crisis risk in full view of stakeholders—the public management of crisis risks (Coombs & Holladay, 2012, 2015. The expansion centered on locating a set of crisis response strategies fitting for paracrises and reputational crises, and identifying the salient factors influencing the communicative response selection decisions in such circumstances (see Table 1.1). There is a greater range of potentially effective options for paracrises and reputational crises due to the more ambiguous nature of these crises. Such crises are more open to multiple interpretations of events and what qualifies as appropriate behavior. You cannot reasonably contest that your facility exploded by choosing to ignore the carnage. You can, however, dispute if your sourcing of raw materials is responsible or choose to ignore activist stakeholders proclaiming your sourcing is irresponsible, such as the Nestlé case discussed earlier. Denial and silence are sub-optimal crisis response strategies for operational crises (Coombs, Holladay, & Claeys, 2016) but can be viable options in a reputational crisis. Reputational crises provide a bridge from SCCT to the discussion of sports crises because sports crises are predominantly reputational. The following sections link SCCT to sports crises by examining the types of crises common in sports and the contextual factors that help both to shape reactions to sports crises and to influence the effectiveness of various crisis response strategies during sports crises.

p.16

TABLE 1.1 Factors That Could Influence Response Selection to ARCs

Sports and Crisis: A Reputational Focus

Sports reporters often use the term “optics” to refer to actions of a team, league, or individual that does not look good to stakeholders. This term captures the reality that most sports crises are reputational rather than operational, because most sports crises do not threaten the delivery of services. In Communication and Sport: Surveying the Field, the examples used in the chapter on crisis communication are predominantly reputational (Billings et al., 2015). Koerber and Zabara (2017) noted that sports crises rarely reach the level of serious damage or disruption of business, two common definitional characteristics of a crisis (Coombs, 2015). Riots, terror attacks, and other operational disruption do occur in sports, but reputational crises are far more common. Koerber and Zabara (2017) warn that the reputational bias in sports crises “should not be taken to mean that sports crises are inherently less significant than crises in other fields” (p. 194). Rather, there is simply a difference in the nature of crises in sports versus other organizations. This section refines the sports crisis focus of this chapter and the potential implications for adapting SCCT to sport.

Clarifying the Focus of Sports Crises

Sato, Ko, Park, and Tao (2015) developed the concept of athlete reputational crisis (ARC). An ARC is “an event caused by (un)intentional and on (off)field athlete behaviors that threaten to disrupt an athlete’s reputation” (Sato et al., 2015, p. 435). An ARC can involve intentional or unintentional behaviors that can occur on or off the field, hence covering a variety of events. There are other types of sports crises, but the focus in this chapter is on ARCs. In crisis management there is the concept of spillover, when a crisis affects other related entities not directly involved with the crisis (Roehm & Tybout, 2006; Zavyalova, Pfarrer, Reger, & Shapiro, 2012). For instance, spillover occurs when a crisis with one product of a company has negative effects for the company’s other products or a crisis for one company affects an entire industry. In 2011, Listeria in cantaloupe from one farm in Colorado killed 33 people and had a devastating effect on the entire cantaloupe industry, because people were afraid to eat any cantaloupe. Even two years later, the cantaloupe industry in Colorado was still suffering the spillover effects (Whitney, 2013). ARCs can have a spillover effect on teams, leagues/associations, and sponsors. If the athlete is involved in a team sport, his or her actions can negatively affect the team. Team sports belong to associations and ARCs can create reputational crises for those associations as well. The Ray Rice domestic abuse crisis created a spillover effect for the Baltimore Ravens (team) and the National Football League (association; Richards, Wilson, Boyle, & Mower, 2017). Some athletes are in individual sports such as tennis or golf. Still, there are associations overseeing these sports and an ARC can raise crisis risks for the association. Individual athletes using performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) creates problems for various, including the International Olympic Committee.

p.17

The spillover potential of an ARC creates a coupling between the individual athlete and the larger system (teams, associations, and/or sponsors) that reflects a multivocal approach to crisis communication (Frandsen & Johansen, 2010, 2017), ARC communication should consider both the response of the athlete and the response of the larger system. I am not saying these responses are coordinated but they will affect one another; hence, it can be insightful to examine ARCs as crisis communication networks.

The ARCs and SCCT

This section explores the fit between SCCT and ARCs. The consistencies between ARCs and SCCT are developed along with ways SCCT needs modification for application to ARCs. Crisis types and contextual modifiers supply the guiding points for this section.

Crisis Types

Within the scope of ARC, there are a variety of crisis types. Consistent with the organizational crisis communication literature, ARC research found that crisis type does shape attributions and reactions of stakeholders (Sato et al., 2015). A 2 × 2 matrix of ARC types has been created using intentionality, and performance draws from Attribution Theory, as does SCCT. Performance is whether the event is related to athletic performance or off the field (non-performance related). Taking PEDs would be classified as performance, while domestic abuse more befits the non-performance domain. Attitudes toward an athlete were found to be more negative for intentional actions and performance-related actions. The reason for the difference is tied to the fact that performance actions result in people quest...