![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1

The promise of and the need for citizen science for coastal and marine conservation

John A. Cigliano and Heidi L. Ballard

The dramatic expansion in recent years of the approach to scientific research that involves members of the public in one or more stages of the scientific process, typically called citizen science, immediately raises a wide range of questions. How reliable are the data that come from volunteer data collectors? Who are the participants in these projects, where do they come from, why do they volunteer to do this work, and what do they get out of it? Can these data be used for real natural resource management and conservation decisions? Can citizen science project findings be used to inform conservation policy? Can indigenous knowledge be a part of citizen science, and what are the ethical issues around data ownership and real collaboration? Where in the world is citizen science really happening? Is this just a fad, or a significant transformation of the way science can be conducted, who can do science, and how science can contribute to conservation?

In no context are these questions being asked and answered more clearly than in coastal and marine conservation. Coastal and marine social-ecological systems have a rich history of collaborative natural resource management, local and traditional ecological knowledge holders partnering with scientists, and monitoring to inform decision-making. These systems also have a history of conflict and tensions between science and management, between livelihoods and recreational use, and between locals and tourists, and difficulty in getting quality data across broad spatial and temporal scales. Perhaps most urgent, coastal and marine systems are ground zero for the impacts of climate change, species loss, habitat destruction, sea-level rise, ocean acidification, and myriad other conservation threats. All of these threats, and our responses in the form of adaptation and mitigation, require new kinds of data and data collection, and new kinds of engagement with stakeholders, including scientists, managers, businesses and non-profits, people who live on the coast, people who fish and depend on natural resources, and people who recreate and care deeply about our oceans.

We offer this book as a partial answer to the question of whether and how citizen science contributes to coastal and marine conservation. We think it is not a fad, but a new way of doing science for conservation that is more inclusive and can mean more conservation impacts on the ground. However, the rapid expansion of the use of citizen science for coastal and marine conservation does not necessarily mean that these projects are always appropriate, effective, efficient, or ethical. Many projects develop and fail without significantly impacting conservation, providing quality data to scientific research, or engaging members of the public in sustainable ways. Our goal is to provide examples of coastal and marine citizen science projects that have contributed to conservation through research, education, management, and/or policy, and illustrate how they are structured to do so, from volunteer recruitment and retention to data quality control and assurance. Citizen science is not the only effective approach to coastal and marine conservation science, but it can be a powerful one if designed and implemented well, drawing on the lessons of the many projects working on similar goals and in similar contexts.

What is citizen science?

Citizen science, or as it is also referred to, public participation in scientific research (Shirk et al., 2012), has several definitions. The Oxford English Dictionary defines citizen science as “the collection and analysis of data relating to the natural world by members of the public typically as part of a collaborative project with professional scientists.” However, Bonney et al. (2016) correctly points out that this definition does not include the fact that citizen scientists often go beyond collecting and analyzing data, that they often work as individuals often without directly collaborating with scientists, and that many projects are community-driven (see “Typologies of Citizen Science”).

Here we distinguish between the public collecting and sharing data for their own or even their community’s education and awareness, and the public collecting data that are used, reviewed, and acted upon by other scientists and/or resource managers for basic science or natural resource management. In this book, we follow and apply the definition that citizen science is scientific research and monitoring projects for which members of the public collaborate with professional scientists to collect, categorize, transcribe, or analyze scientific data, and may also help define the research questions and design, as well as communicate and act on the project’s findings, a definition consistent with Bonney et al. (2014). That is, the public contributes to and participates in one or more steps of the scientific process. However, it should be noted that while citizen science projects have scientific goals and objectives at their core, they may also have social and educational objectives and outcomes (Bonney et al., 2014); for example, in Chapter 11 Ann Wasser discusses the educational benefits of involving middle-school students in monitoring, and in Chapter 8 Jane Disney and colleagues discuss the community benefits of their restoration project. This book will focus on evidence and processes for how citizen science has been used to advance coastal and marine conservation, and most importantly, how this might inform future use of this approach.

The growth and promise of citizen science for coastal and marine conservation

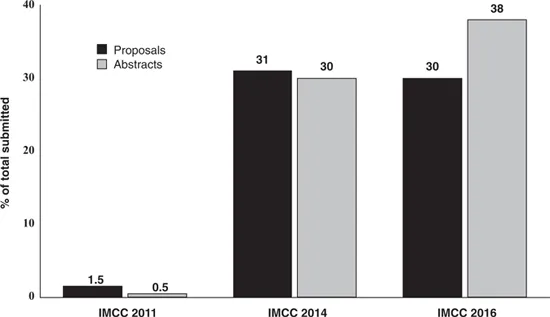

The use of citizen science has dramatically increased in recent years (Conrad and Hilchey, 2011; Follett and Strezov, 2015; Kullenberg and Kasperowski, 2016) and has had positive impacts on conservation research in general (Theobald et al., 2015). However, the use of citizen science in coastal and marine contexts is under-represented compared to its use in terrestrial and freshwater research and monitoring (Roy et al., 2012). Even so, coastal and marine citizen science has shown significant growth in the last several years as evidenced by the growth in citizen–science related presentations and organized sessions at the International Marine Conservation Congress (IMCC), which has become one of the largest professional meetings solely devoted to coastal and marine conservation (Figure 1.1), and an increase in the number of publications of marine-related studies that used citizen science (Thiel et al., 2014). Further evidence for the potential for continued growth in coastal and marine citizen science is provided by Martin et al. (2016), who found in a study of potential marine citizen scientists that there is significant interest in citizen science among marine users (primarily SCUBA divers).

Figure 1.1 Percentage of proposals and abstracts submitted under the citizen science theme (Participation in Marine Conservation Science). Proposals include workshops, focus groups, and symposia. Abstracts include oral, speed, and poster presentations. IMCC 2011 did not have a citizen science theme and the number of proposals and abstracts represent the number of each that had “citizen science” in the title or abstract.

Why use citizen science for coastal and marine conservation?

There has been a significant amount of discussion on the utility of citizen science for ecological and conservation-related research, and these reasons are applicable to coastal and marine conservation. Many of the reasons given for the value of citizen science are based on the fact that using volunteers can lead to a large increase in the number of researchers (professional and volunteer) working on a project. The greatest strength of citizen science is often suggested to be that it allows for the collection of fine-grained information over greater spatial and temporal scales than conventional research projects and that it allows for the processing of large amounts of data (Miller-Rushing et al., 2012; McKinley et al., 2015). The increase in the number of researchers can also increase the likelihood of detecting environmental perturbations and changes, lead to better monitoring of the effectiveness of management practices as part of an adaptive management program, and fill in data gaps. Citizen scientists can also represent a source of free labor and a possible source of financing (Silvertown, 2009). Jenny Cousins and co-authors in Chapter 3 discuss a mangrove project that employs Earthwatch volunteers who pay a fee to join the project. A portion of this fee goes to researchers to support their research, thus providing both funding and enthusiastic citizen scientists.

But the value of citizen science goes beyond just numbers. Citizen science can also allow for projects to operate at times when professional scientists are not collecting data (Miller-Rushing et al., 2012). Citizen scientists can also help refine research questions because for many projects the citizen scientists are locally connected to and affected by the issue being addressed by the project; citizen scientists can also assist researchers in understanding the social dimensions of the project among the stakeholders (McKinley et al., 2015). Miller-Rushing et al. (2012) also suggest that citizen science allows for projects to be conducted that would not be done by professional scientists, for example, because the question is too narrow in scope to appeal to a large audience of professional scientists or to be widely cited in scientific publications. And McKinley et al. (2015) suggest that citizen science can lead to broader public participation in policy decisions (see also Cigliano et al., 2015), foster environmental stewardship, and promote the spread of knowledge about the conservation issue and project through the social networks of the citizen scientists.

We would also add that conducting citizen science projects can be enjoyable and rewarding for professional scientists because of the enthusiasm and curiosity that the citizen scientists bring to projects. And working with an excited and engaged public who are so willing to give their time, effort, and sometimes money to help conserve and manage biodiversity can provide real hope for the future (#OceanOptimism) to professional scientists who have seen environmental degradation and species extinction up close and too often.

Typologies of citizen science

While all citizen science projects (as defined here) share the goal of producing quality scientific data, several citizen science typologies have been developed to describe the degree (Shirk et al., 2012; Haklay, 2013) and quality (Shirk et al., 2012) of participation by citizen scientists, the organizational and macrostructural properties of the projects (Wiggins and Crowston, 2011), and project outcomes (Cigliano et al., 2015). Other typologies have been proposed, but we will limit our review to these because of their usefulness for describing and categorizing coastal and marine conservation citizen science projects. Understanding the various typologies is useful when planning such projects because it can help define the goals and expected outcomes of the project and help in designing project methodology including how best to utilize citizen scientists (Shirk et al., 2012). However, we don’t see these typologies as set in stone or mutually exclusive; they are a useful way to disaggregate the factors, processes, goals, and outcomes of coastal and marine citizen science projects to analyze their outcomes and design better programs and projects in the future.

Degree and quality of citizen scientist participation (Shirk et al., 2012)

Why develop a typology based on the degree and quality of participation by citizen scientists? Shirk et al. (2012) found that the degree and quality of a citizen scientist’s participation are closely related to the range and types of project outcomes, and that having a framework based on participation can inform project design. Shirk et al. (2012) defined degree of participation as the extent to which citizen scientists are involved in the scientific process (i.e. from formulating questions to analyzing data and dissemination of results). Quality of participation describes how well the project’s goals and activities “align with, respond to, and are relevant to the needs and interests” of the citizen scientists. By considering the degree and quality of participation, Shirk et al. (2012) developed models of citizen science based projects (degree of participation) and a framework that can be used for project development (quality of participation).

Five models based on degree of participation were developed. Three of them include contributions from citizen scientists in collaboration with scientists. They are:

- Contributory projects: designed by professional scientists; citizen scientists primarily contribute data; these are often projects that need to collect data on a large geographic or temporal scale;

- Collaborative projects: projects that are also designed by professional scientists; citizen scientists primarily contribute data but may also help to refine project design, analyze data, and/or disseminate findings;

- Co-created projects: designed by professional scientists and the public, where at least some of the public participants are actively involved in most or all aspects of the research process; these projects are often initiated by the public, and collaborating with scientists is done to ensure that the project is conducted in a scientifically rigorous manner.

Quality is central to design and implementation of citizen science projects, because it reflects whose interests can and should be considered and negotiated, and how the project’s goals or outcomes are defined. The fundamental question of this framework is “whose interests are being served?” The elements of the framework include inputs (hopes, desires, goals, and expectations of the professional scientists and citizen scientists); activities (tasks necessary to design, establish, and manage a project); outputs (initial products or results of activities); outcomes (measurable elements such as skills, abilities, and knowledge that result from the specific outputs of a project; measured within 1–3 years of project start); and impacts (long-term and sustained changes; occurs 4–6+ years after project starts). Shirk et al. (2012) identified three categories of outcomes: (1) for science, (2) for citizen scientists, and (3) for socioecological systems, and suggests that for a project to be sustainable, it must yield outcomes in all three categories.

Level of participation and engagement in citizen science activity (Haklay, 2013)

Haklay (2013) also developed a typology based on participation but focused on the level of participation and engagement by the citizen scientists. This typology focuses on the level of participation because it is indicative of the power relationships that occur within social processes, such as planning or decision-making. This is particularly relevant to conservation-related citizen science because ultimately these projects are collecting information for use in management and planning.

The typology proposed by Haklay (2013) from most passive to most active includes the following categories:

- Crowdsourcing: a process of obtaining data by soliciting contributions from a large group of people, especially from an online community;1 participation by citizen scientists is limited to providing data with limited cognitive engagement; citizen scientists act as “sensors,” and engagement between citizen scientists and professional scientists is indirect.

- Distributed intelligence: citizen scientists provide their the cognitive abilities to the project; after some basic training, citizen scientists conduct simple interpretation activities; engagement between citizen scientists and professional scientists is indirect.

- Participatory science: the research question is determined by the citizen scientists with professional scientists acting as consultants to develop data collection and analysis methods, thus the citizen and professional scientists are directly engaged; citizen scientists collect data, but require the assistance of the professional scientists in data analysis and interpretation, but can suggest new research questions based on the data analysis; this type of citizen science is particularly relevant to “community science.”

- Extreme citizen science: there is direct engagement between professional and citizen scientists, and citizen scientists are assumed to be in comparison to professional scientists equally capable in the production o...