![]()

Part I

What are markets?

![]()

1 Defining markets

Markets and trade have always been central to economic theory. Often the very idea of an economy is assumed to begin with trade that yields mutual gains for all. Economics teaching dwells at length on markets, as in the supply-and-demand diagram, the most widespread of textbook models. Since markets are so prominent, one might expect that they would be well defined. This is not the case, and economists seldom bother to define them or explore their background. They are mentioned frequently but casually, as if their meaning were obvious and required no further explanation.

The absence of an agreed definition sits oddly with the supposed rigour attained by economics. Markets are conflated with exchange, evading a proper definition adopted across the discipline (Hodgson, 1988, chapter 8, 2008; Sawyer, 1993; Sayer, 1995, chapter 4; Rosenbaum, 2000). Theoretical models focus on trade among rational agents and say little about markets per se. References to markets crop up randomly as a substitute for exchange or trade, without distinguishing features. Any trade can be classified as a market, which becomes a catch-all term that conveys little useful information. The origins and historical background of markets are not stressed in mainstream economics, nor are the variations in their details and operation. Hazy characterisation of markets opens the door for many inconsistencies.

Attempts to find a definition of markets must start with the linguistic sources of the word and its everyday usage. ‘Market’ derives from the Latin mercatus (trade), its first appearance in the English language going back to the medieval period, around the twelfth century (Davis, 1952; Aspers, 2011, chapter 1; Eagleton-Pierce, 2016, pp. 118–124). Early references to markets had a geographical aspect, such that the market was the physical location of trade. A medieval market town would have one or more open areas (market places) where traders in particular commodities could meet to conduct business. Prior agreement to meet at certain times and places suggests that markets must be organised and do not happen spontaneously. Market trade goes beyond a random encounter of two people who make a one-off trade: it implies regular, standardised trading on a large scale. From the outset, markets have been organised commerce rather than informal exchanges between individuals.

While the geographical meaning of a market can still sometimes apply, it has receded during economic development. Modern trade extends to national or international levels and has less need for a physical location – improved communication allows it to occur without meeting in person to transfer goods or money. The meaning of a market has broadened to cover trading for a particular commodity at any location. Markets are then delineated by the commodity traded, not the place of trade. Relaxing the geographical aspect leaves intact the significance of prior organisation, which if anything becomes more important as the size and complexity of the economy increases. In trying to find an all-purpose definition, one possibility is to regard markets as ‘organised and institutionalised exchange’ (Hodgson, 1988, chapter 8, 2008; Adams and Tiesdell, 2010). This distinguishes them from casual trading and does not restrict them to a certain place of trade. They become one kind of exchange among others, no longer equated loosely with any exchange.

The organised nature of markets narrows down their definition but remains vague about their structural details (Fourie, 1991; Jackson, 2007b; Fernández-Huerga, 2013; Ahrne, Aspers and Brunsson, 2015). Trade can be organised in different ways, and perhaps only some should be termed a market. Many questions go unanswered. What kind of organised trade do we mean? Does it have to be competitive? Can traders bargain and make personal arrangements? How are prices determined and how do they adjust? Are traders provided with the same accurate information? Can anyone enter or exit the market? Does a higher authority administer the market? A complete account would have to answer such questions and specify the organisation that separates market from non-market trade within the larger economy.

Markets in relation to production and consumption

The basic activities common to all economies are production, distribution and consumption. They are in a temporal sequence: goods are first produced, then distributed, then consumed. Trading is a distributive exercise, in that it does not entail production of new outputs or consumption of existing outputs. When trade occurs, some items are exchanged for others to bring about voluntary redistribution. The traders can be producers, consumers or intermediaries specialising in trade, hence the part played by trade in binding the economy together. Although trade spans the whole economy, it can best be classified as distribution and distinguished from production or consumption.

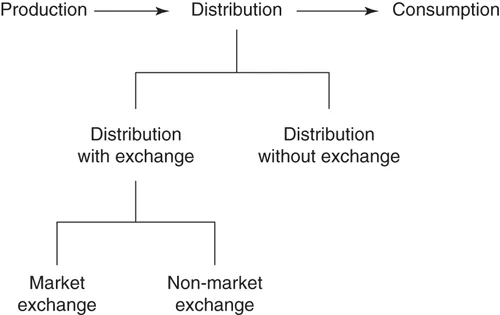

Distribution takes various forms, only some of which should be labelled as trading; examples of distribution without trade are communal sharing, gifts, governmental allocation and allocation by firms and other organisations. Trading stems from voluntary exchanges of property, whereby traders agree to reassign property rights. Exchange, like distribution, has many variants (Davis, 1992, chapter 2; Biggart and Delbridge, 2004; Hann, 2006). Markets can be interpreted as voluntary exchanges that are organised and institutionalised so as to ease trade. By this interpretation, they are a subset of exchange, which is a subset of distribution. Figure 1.1 shows the overall picture.

Figure 1.1 Markets, exchange and distribution.

Distribution in Figure 1.1 refers to the allocation of goods or other resources among people or groups, irrespective of how this is accomplished. Exchange occurs when voluntary property transfers influence the final allocation – it is commonplace in modern economies but not universal. Much distribution within government, firms and households goes ahead without exchange and without markets. To have agreed, binding exchanges presupposes property rights, so that participants abide by the property transfer. This necessitates both property law, defining the rights of property ownership, and contract law, regulating voluntary transfers of property (Commons, 1924; Prasch, 2008, part 1). Involuntary transfers will break the rules and be declared illegal as theft, burglary, fraud, etc.

Markets in Figure 1.1 are organised and institutionalised exchanges, as distinct from less formal exchanges, such as reciprocal gifts, personal trading relations and bargaining. They have never become so prevalent that they entirely displace non-market exchange. As Figure 1.1 attests, they are less fundamental to the economy than one might think from economics textbooks and should not be accorded primacy.

Defining markets as organised and institutionalised exchange may be too broad to have real discriminating power. Almost all exchange will be organised to at least a minimal degree, and the market/non-market distinction may turn upon the nature of organisation as against its existence. A more satisfactory definition should arguably go further and specify the organisational details that distinguish a market. This is far from straightforward. The fact that few textbook writers address the question, which would seem vital to an introductory treatment of economics, indicates the difficulties.

Attributes of markets

What, then, are the organisational and institutional attributes of a market that distinguish it from non-market exchange? Table 1.1 sets out some institutional features often associated with markets. In the earliest definitions of markets, they are a location for trade. At one time, it would have been a physical location; nowadays it may be virtual or electronic, as in financial markets or internet auction sites. Markets should facilitate trade by being accessible to potential traders – closing access off for any reason will breach the spirit of market trading. Each market should generate a known price or rate of exchange for a certain good. Public availability of reliable information on goods and prices is among the main features of a market. Also pertinent is an acceptable and feasible payment method. Transfers of goods on a market must be carried out either at the location of trade or through some other mode of delivery. Regulation ensures that property transfers are lawful; arbitration resolves trade disputes.

Table 1.1 Institutional features of a market

| Location | A physical or other location for trade is provided. |

| Access | Trade is open to anyone wishing to participate. |

| Pricing | Goods are exchanged at a standardised monetary price. |

| Information | Accurate details of goods and prices are published. |

| Payment | There is an agreed and acceptable payment method. |

| Delivery | Arrangements are made for the delivery of traded goods. |

| Regulation | Rules are in place for lawful property transfers and good trading practices. |

| Arbitration | Procedures are agreed and implemented for resolution of trade disputes. |

Insisting on the features in Table 1.1 would not provide an agreed market definition. What we call a ‘market’ in common usage may miss out on some of them. Barriers to entry, for example, are legion and deny open access to trade but are treated as compatible with market status. Many markets have differentiated products, no standardised prices and poorly informed buyers. Regulation is another variable. Only a fraction of trade in the real world possesses the full set of market features. There can be no simple checklist of attributes that define a market.

Alternatively, we can look towards the characteristics of market trade, rather than the market itself, as in Table 1.2. Market trade should be voluntary for all participants and a two-way exchange of one item for another. Money is normally the medium of exchange, which enables traders to perform repeatable transactions. Standardised goods are bought and sold at published prices. Nobody should be excluded from trading, which depends only on the ability and willingness to pay. Traders are supposed to care only about the item traded and its price, so they do not form personal relationships with trading partners. The impersonal quality of market trade opens it up to competitive behaviour, where people switch trading partners to get a better deal.

Table 1.2 Characteristics of market trade

| Voluntary | Transactions are voluntary, with no compulsion on either sellers or buyers. |

| Two-way | One item is exchanged for another, so re... |