![]()

1

Introduction: Juvenile Delinquency, Substance Use, Sexual Behavior, and Mental Health Problems

Juvenile problem behaviors affect us all. Multitudes of parents are confronted by their child’s stealing, early sexual behavior, serious substance use, or prolonged depressed moods. At home, parents may see endless harangues and quarrels in which children and their siblings may become participants as well as victims. Parents are often afraid that their child will not outgrow serious problem behavior and might become chronically delinquent, addicted to alcohol or drugs, or mentally unstable. Teachers find their main mandate in the classroom thwarted by students who disrupt academic courses, bully fellow students, bring weapons into the school, or simply become chronically truant.

Outside of the family and the school, the impact of juveniles’ problem behavior on society is colossal. Huge numbers of delinquent youth are incarcerated in detention centers and large numbers of youth with substance use and mental health problems are brought to detoxification centers and assessed and treated by mental health professionals (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Burns, 1991). In addition, many youth damage their health by the consumption of harmful substances suffer from serious anxiety, depression, withdrawal, and commit suicide.

Another major area of concern is youths’ emulation of adult behaviors, including drinking alcoholic beverages, driving cars, having sexual intercourse, or staying out late. Adolescents’ increasing demands for independence in these areas may clash with the interests of and protection offered by parents. Often parents and their children disagree about the timing of children’s independence from their parents; to some extent, conflict around this theme can be considered normal. However, a minority of youth presses to become more independent at what is generally considered to be a premature age.

Epidemiological surveys have provided key information about the prevalence and degree of seriousness at different ages of a wide array of child problem behaviors in such domains as delinquency (Glueck & Glueck, 1950; Magnusson, 1988; West, 1982; West & Farrington, 1973, 1977), substance use (Kandel, Yamaguchi, & Chen, 1992; Pulkkinen, 1988; White, 1988), early sexual behavior (e.g., Jessor & Jessor, 1977), and mental health problems (e.g., Cohen & Brook, 1987). Because the prevalence of these problems changes dramatically between childhood and adulthood, cumulative prevalence curves help document when changes in prevalence accelerates or slows down. However, such curves do not demonstrate the cessation of deviance.

Problem behaviors should not be seen as inevitable, as is evident from historic variations in the level of juvenile problem behavior. We are convinced about the necessity to document the extent of problem behaviors in current generations of youth. This we can accomplish by studying developmental sequences of problems, thereby establishing continuity among behaviors over different periods of children’s lives. A further improvement will take place by identifying critical precursors that explain why some youth and not others engage in serious delinquency, substance use or early sexual behavior or suffer from mental health problems.

Knowledge of the extent and changes of these problem behaviors is important for several reasons. In general, interventions and health planning can be difficult when the extent of the problems and their course over time are unclear. Also, understanding which risk and protective factors apply to which problem behaviors, and whether particular risk and protective factors can best explain some but not other problem behaviors, is essential for the formulation of theories that form the basis of interventions.

CONTINUITY AND DEVELOPMENT

Continuity

Evidence about the continuity of problem behaviors has been mounting (Blumstein, Cohen, Roth, & Visher, 1986; Caspi, Moffitt, Newman & Silva, 1996; Loeber, 1982; Pulkkinen & Hurme, 1984; Sampson & Laub, 1993). Male aggressive and delinquent behavior is often highly stable over several decades (Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1987; Olweus, 1979). Also, numerous studies have linked early physical aggression to later violence (Farrington, 1991), early tobacco consumption to later drug use (Ellickson, 1992), and early depressed mood to later clinical depression (Kovacs, Paulauskas, Gatsonis, & Richards, 1988). Similar findings apply to conduct disorder. For instance, in a study of clinic-referred boys, Lahey (1995) showed that 87.7% of the boys with a diagnosis of conduct disorder continued to qualify for a diagnosis of conduct disorder in the next 3 years. Similarly, Farrington (1992a) found that 76% of males convicted between ages 10 and 16 were reconvicted between ages 17 and 24. Although such stability is in evidence within the same category of behavior over time, it is essential to broaden the inquiry about continuity by studying a wider range of related behaviors. For example, in the domain of disruptive behavior, Farrington (1991) analyzed the continuity of behavior from ages 8–10 to age 32 in the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. More than twice as many of the most disruptive males at ages 8–10 were convicted for a violent offense by age 32 as the remaining, less disruptive boys at ages 8–10.

In the area of substance use, studies have shown moderate levels of stability over time (Maddahian, 1985), but such stability depends on the age at which the use is first measured and the type of substance. As to mental health problems, in many studies, the stability coefficients for externalizing problems are substantially higher than those for internalizing problems (Achenbach, 1985; Capaldi, 1992).

The stability of behavior is often difficult to gauge prospectively. However, looking back over individuals’ lives, it is often more apparent which types of behaviors in an individual’s life are stable or not. Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber (1987) reviewed prospective and retrospective studies and concluded that, when viewed retrospectively, the majority of adult chronic offenders had acted in a disruptive manner during their elementary school years. This high degree of stability, as Robins and Ratcliff (1979) and Zeitlin (1986) pointed out, implies that serious antisocial behavior rarely emerges de novo in adulthood and instead typically begins much earlier in life.

Thus, there is considerable evidence for the continuity of problem behavior. However, looking prospectively, continuity is far from perfect and, therefore, predictions from early problem behavior to later problem behavior are usually not high. Moreover, continuity is usually not limited to the stability of the same behaviors over time. Also important is heterotypic continuity (i.e., the continuity among different problem behaviors over time). Often heterotypic continuity occurs primarily because new problem symptoms are added to existing ones, gradually leading to a diversification of problem behavior (Loeber, 1988).

Development

Many problem behaviors in childhood and adolescence can be considered age normative, in that they occur more often at certain age periods than others. For example, separation anxiety early in life and highly oppositional behavior later are both common (Loeber & Hay, 1994). Therefore, in several ways, numerous problem behaviors can be thought of as developmentally normal at some ages. However, there are at least three criteria to use in judging whether problem behaviors are deviant. First, child problem behaviors can be considered deviant when they persist during periods in which most youth have outgrown such behaviors. An example is the persistence of highly oppositional behavior during the elementary school-age period. Second, a problem behavior is deviant if it results in a high degree of impairment (e.g., when the withdrawn behavior is so serious that affected children refuse to go to school and suffer in their academic performance, or when substance use seriously affects personal relationships). Third, problem behaviors are deviant when they result in harm to others. Examples are violence and theft of others’ property.

A critical issue in the study of children’s behavior is our lack of knowledge about how best to (a) discriminate prospectively between those youngsters who will outgrow their early problem behaviors and those who will not, (b) discriminate between youth who will become impaired in functioning because of their problem behavior and those who will not, and (c) differentiate between those youth whose infliction of harm is transitory and those who are on the road to persistence in these behaviors.

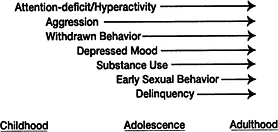

In recent decades, researchers have started to look beyond prediction and have focused on deviancy processes that take place during the interval between the occurrence of a predictor and an outcome (Loeber & Le Blanc, 1990). There are several reasons why this question is critical. The development of delinquency, substance use, early sexual behavior, and mental health problems often takes place gradually over time, with some behavior problems starting earlier than others but most taking years to reach a serious level. This is illustrated hypothetically in Fig. 1.1. We are learning more about the ordering of the development of problem behaviors from childhood to adolescence, both about development within particular domains (Belson, 1975; Loeber et al., 1993; Robins & Wish, 1977; Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1984) and about parallel development between domains (Caron & Rutter, 1991; Loeber & Keenan, 1994; Nottelmann & Jensen,

1995). The latter, often discussed in terms of comorbidity, helps us better understand which youth are most at risk to develop, for example, both disruptive behaviors and mood problems.

The preceding discussion illustrates several points. First, predictions are far from perfect, indicating that we are not yet able to predict adequately which youth are most at risk for later serious maladjustment. Second, a proportion of youth shows highly stable problem behavior over time. Third, processes leading to serious deviant behavior usually are incremental and take years to become apparent and in full bloom. Fourth, some youth are more at risk than others to develop comorbid conditions. Fifth, youth who desist or improve overtime are an important group to study.

A SINGLE PROBLEM THEORY OR THEORIES OF DIS...