- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing Displays for Older Adults, Second Edition

About this book

This book focuses on the design of displays and user interfaces for the older user. Aging is related to complex mental, physical, and social changes. While conventional wisdom says getting older leads to a decline, the reality is that some capabilities decline with age while others remain stable or increase. This book distills decades of aging research into practical advice on the design of displays. Technology has changed dramatically since the publication of the first edition. This new edition covers cutting-edge technology design such as ubiquitous touchscreens, smart speakers, and augmented reality interfaces, among others.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Designing Displays for Older Adults, Second Edition by Richard Pak,Anne McLaughlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Human-Computer Interaction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter one

Introduction

This book is intended as a guide to designing technology to enable older adults (generally defined as over age 65) to live independently, happily, and healthily for as long as possible. With that in mind, the technologies selected for evaluation revolve around home, work, personal mobility, and health. In each of these use cases, we discuss how current or future systems might be designed for older adults’ capabilities, limitations, and preferences. Regarding the home, the concept of aging-in-place, or older adults’ desire to live independently in their home as long as possible, is one area that can clearly be facilitated by technology. New technologies such as smart home devices are making this even more likely than before. Related to aging-in-place, technology is enabling older adults to be more aware of their health and to help them manage conditions that once required specialized equipment. In the realm of work, older adults are choosing (or need to for financial reasons) to remain in the workforce longer. Even after retirement, they may be increasingly likely to pick up part-time jobs that allow them to work from home for extra income or volunteer positions that also decrease social isolation. Finally, in the past few years, personal mobility options have increased with the rise of ridesharing. The landscape of technological change coupled with these new societal trends heavily informed our selection of systems to evaluate (second half of the book). In the following sections, we further detail demographic and technological changes since the publication of the last edition.

1.1 Demographics and health trends

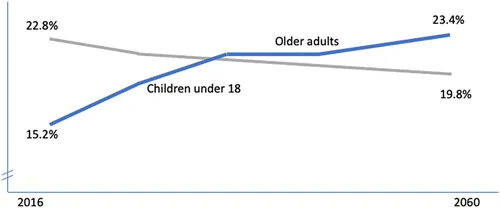

As of this writing, almost 50 million people in the United States are over age 65. In the coming years, the U.S. Census estimates this figure will double. This is an economically powerful group that will impact every aspect of American life (Figure 1.1).

In the United States and around the world, aging brings a brighter outlook than ever before. Advances in healthcare, nutrition, disease treatments, and supportive infrastructures are enabling successful aging across a wide socio-economic spectrum. For example, 100 years ago, the average lifespan was much shorter and the income level of most countries in the world was below a living wage. In the last few decades, the lifespan in the United States has increased to 78 years and personal wealth is much higher. This is not to say there is not serious inequity in the world – averages do not convey the difference in opportunity and income for those born into wealth versus those born into poverty, but technology may increase the opportunities for health, social interaction, and intellectual engagement for all.

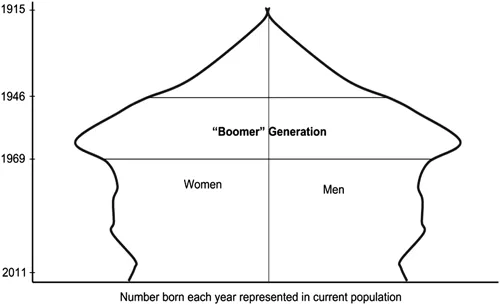

Such equity is becoming increasingly important as the world ages. An extremely high birth rate after the end of WWII combined with lower birth rates since has resulted in a world that looks demographically different than ever before in human history. The distribution of human age has typically been a pyramid, with most humans under age 5 and fewest over age 80. This pyramid has become inverted, and is becoming more so, with a prominence of older persons dominating the figure (Figure 1.2).

This change in the distribution of ages is crucial for a number of industries. In healthcare, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the number and cost of treatments for age-related diseases and multiple conditions have risen. Specialists in gerontology and caring for older adults are in high demand, and accessible homes and independent-living centers are growing in number under government regulations meant to create a safe and secure environment for all (U.S. Census; Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)). In the workforce, older adults are working longer, retiring later (or “never,” Drake, 2014), and seeking out part-time and volunteer opportunities. These demographic changes are even becoming visible in the entertainment world, as movies and TV shows focus more on aging audiences and providing meaningful and hopeful views of life after 65. Statistics from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) show that older adults like to and are able to travel more than younger adults. A common thread is the importance of supporting older adults in leading the lives they want to live: as independently as possible, financially secure, and socially and intellectually engaged.

Being more aware of one’s own health and maintaining independent mobility are two key components of independent living. They also represent areas where there is a large technological change (e.g., wearable health monitoring, ridesharing apps, and self-driving cars) – changes that might make it difficult for older adults to reap the purported benefits. Age-related changes still occur, with the outcomes that older people may have trouble seeing, hearing, processing, reacting, or deciding as quickly and as accurately as their younger counterparts. These senses and abilities are the core of interactions with the world, and if they decrease, so do interaction with and understanding of a multitude of interactions and technologies, from being able to hear and understand the voice of a stranger in a crowded street to being able to navigate to new places to understanding what new technologies offer enough of a benefit to be worth the time, effort, and cost of investing in them. There are enough older persons in the United States to have an impact on national trends in mobility: the Pew Research Center shows few people change cities at older ages (Cohn & Morin, 2008). Another Pew report found that older adults are now more likely to live alone (Drake, 2014), probably due to increased financial security and their desire to live by themselves. Studies such as these are not only an important glimpse into motivation and ability, but also a hint at the kinds of technologies that might be needed to support a person living alone at an advanced age.

1.2 How older adults use technology now

The foregoing demographic and health trends translate into use of technology. It has long been known that older adults are interested in new technologies. When this interest does not translate into use, it is likely due to certain potential barriers: cost, inaccessible design, and usability issues. Despite these challenges, older adults choose to invest in particular technologies. For example, Pew reports that 12% of people over 65 report using a dating app to find potential romantic partners, half use Facebook, and that use is highest in the “youngest old” (ages 65–69) and in the most highly educated and financially well-off.

In the last edition of our book, we noted that “Those over age sixty-five are less active users of the full range of advanced mobile services, but they are enthusiastic users of mobile voice communications, especially in emergency situations.” This is still true, but the gap is closing; 95% of adults aged 65–69 and almost 60% of adults over 80 own a cell phone. The numbers of smartphone users are lower but still substantial: overall 42% own a smartphone, meaning roughly 21 million smartphones are in the hands of older adults. E-readers, such as the Kindle or electronic tablets, are also popular with one-third of older adults owning tablets and one-fifth owning e-readers (Smith & Anderson, 2018).

Although it is not linked to a particular technology, many older adults are returning to school and facing the changes and technological innovations colleges have introduced, from e-textbooks to online courses, to methods of classroom and group communication (wikis, messaging services, etc.).

1.3 State of the art and what the next 10 years will bring

Given the technological changes of the last 10 years, it is a useful exercise to consider what the future may look like in the next 10 years. We will discuss trends in user interaction paradigms, task contexts, use cases, and technology form factors, followed by the principles of human factors and aging to evaluate these trends for older adults’ usability. The goal is not to specifically evaluate existing technology – instead, it is to illustrate a methodology, assist in identifying applicable scientific literature, and focus evaluation efforts around the needs of older adults.

First, while the technology may look different and be more ubiquitous, there are ways to leverage past research into these new, unforeseen domains. As an example, voice-based interaction is rapidly being used to interact with new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) assistants in the phone, car, and home. However, past work examining interactive voice response systems (IVRS), or voice-based telephone menu systems, is relevant to these new voice assistants. For example, work by Sharit and colleagues (2003) found that when older adults used IVRS, it was helpful to have a visual aid that supported memory. This clearly has relevance when older adults are interacting with voice-commanded systems. To be sure, these new voice assistant systems are different enough to warrant further research, but fundamental discoveries from past research still apply. Unlike IVRS that used a restricted vocabulary and typically had options for alternative input (“Press 1 for…”), voice response systems are more naturally language oriented and have no other options for alternative input. The dilemma is that although they claim to accept natural speech input, there are vocabulary and syntactic constraints that are not obvious to the user. This confusion was illustrated in a popular video of an older woman interacting with a voice assistant (Figure 1.3). In addition, voice systems are sensitive to timing so that pauses are interpreted as ends of commands. In the following paragraphs, we discuss more ways technology might change in the next decade.

1.3.1 Self-driving cars

The purported benefits of a self-driving vehicle for older adults seem obvious; from allowing those without licenses access to easy transportation to reducing the accident rate. However, self-driving cars, perhaps, present an interesting case study of many technologies combined into a single system, each with potentially major usability issues. If the societal benefits of self-driving cars are to be realized, these human interaction problems must be solved. First, for the foreseeable future, self-driving cars will occupy the same roads as human-operated cars. This will prove challenging to both self-driving cars and human drivers, including older drivers and passengers will need to update their expectations about their role as operator (of a self-driving car) or driver surrounded by self-driving cars. How will they react in an emergency? How will they hand-off control and take back control? In addition, numerous studies show cohort differences in the trust of automated systems, with older adults tending to over-rely on some systems but under-rely on others. Trust and knowledge must be paired for older adults interacting with self-driving cars, either as an operator or as the driver of another car on the road.

1.3.2 Digital realities

Another change coming in the next 10 years is likely to be the ubiquitous presence of mixed-reality systems (often called augmented reality [AR] and virtual reality [VR] or mixed reality [MR]). Primitive examples include heads-up displays in automobiles (the overlay of “safe” distance from obstacles in a backup camera is AR), but more advanced versions are likely to be common in the next few years. These systems are currently being targeted to specific technical domains, such as AR/VR/MR systems in healthcare that support surgeons and manufacturing assembly tec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Authors

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Vision

- Chapter 3 Hearing

- Chapter 4 Cognition

- Chapter 5 Movement

- Chapter 6 Older Adults in the User-Centered Design Process

- Chapter 7 Preface to Usability Evaluations and Redesigns

- Chapter 8 Integrative Example: Smart Speakers

- Chapter 9 Integrative Example: Workplace Communication Software

- Chapter 10 Integrative Example: Transportation and Ridesharing Technology

- Chapter 11 Integrative Example: Mixed Reality Systems

- Chapter 12 Conclusion

- Index