![]()

1

Introduction

The couple is a place where we can make a deal to learn our most intimate lessons on the spiritual path. Learning how to live in the couple is healing for the consciousness of all humanity. The crisis of the couple is the crisis of society.

—Oscar Ichazo (founder of Arica® Institute, a school for the development of consciousness)

Men and women need each other more than ever as partners in facing an increasingly demanding and accelerated pace of life.

—Gail Sheehy (author, political journalist, and contributing editor to Vanity Fair)

LIKE UNSEEN hands, many "clocks"—social, psychological, and communicative—guide the course and development of personal relationships. In the field of sociology, researchers have discovered that the way individuals follow "social clock" norms can bear on later developments in life. Our age at different transition points in the life of our closest relationships (first sexual intercourse, first marriage, first child) may be "early" or "late" compared to the average age, and so may influence the nature of those relationships (e.g., Helson, Mitchell, & Moane, 1984). Psychologists have discovered that different social motives may be influenced by early childhood experiences in our families and, in turn, shape how we behave with those with which we choose to seek intimacy. Sometimes our need for intimacy ("I want to be close with someone") may be stronger or weaker than the need for stability ("I like things to run smoothly and in ways I can predict") or the need for change ("I want to have new and exciting experiences"). Communication scientists as well, studying the moment-to-moment behavior of married couples, have discovered sequences of interaction that take on a life of their own. Some couples "lock in" to cycles of interaction, and others have rhythms of communication that are less predictable but nonetheless determine the character of the couple. These clocks work together, a weave of temporal forces, to shape every challenge and opportunity for intimacy and closeness.

Despite the importance of these clocks, relationships—in their most intimate form—move through and even beyond time. In a sort of paradoxical way, when we experience deeply knowing and caring for another, we sense that relationships are not merely temporal, not strictly bound to age, personal need, or chains of events. This book seeks to bridge these two ways of understanding relationships—one temporal and one transcendent of time. It seeks to show that the weave of time that impels relationships is a precious weave that can be known through science as well as direct experience.

Orientation and Definitions: Grasping at Complexity

This book provides seven different ways (in seven corresponding chapters) of understanding intimacy in a more process-oriented or time-sensitive manner. By "process-oriented" I mean that intimacy is not just some goal to achieve or reach—that is, an outcome, a state, phase, or feeling. This goal is often implied when we talk about sexual union, closeness in just being together, an exchange of secrets, or new levels of disclosure. Intimacy can occur just as much, if not more, between, before, or after these occurrences. It is a process of interacting with another in ways that are sensitive to change and nuance. By "sensitive to time" I mean that anyone who thinks about intimate relationships—be it their own or others—can appreciate or be mindful of the effect that time has on such relationships.

This temporal sensitivity has been developing in widely different areas of science. For example, in theoretical biology, Bornstein (l989) wrote about life cycle development in animal and human neurobiology, defining 14 distinct features of "sensitive periods" of development (e.g., hours for ducklings to imprint, days for a bird to learn a song, months to ensure sexual normalcy in monkeys). Certain features demarcate the temporal profile of the sensitive period. These include dating or when the event begins, the rise and decay in terms of setting event and time, the duration or temporal window of susceptibility, and the asymptote (whether the sensitive period is shaped more like a peak or a plateau). In addition, there are temporal aspects to the mechanisms of change, which stimulate the sensitive period, and to the consequences of the sensitive period (e.g., outcome and duration of outcome). Research on "sensitive periods" in personal relationships might benefit from this biological nomenclature.

In counseling psychology, Zhu and Pierce ( 1995) argued that certain time limited forms of counseling could be more efficient if sensitive to issues such as client's learning curve, and probability of relapse. A client's need for counseling is often not a linear function of time. Zhu and Pierce provided the example of "relapse-sensitive" scheduling in recovery from smoking cessation, with sessions scheduled 0, 1, 3, 7, 14, and 30 days after quitting rather than on a weekly basis. In the field of ecology, researchers are discovering that farming and land management practices are also more efficient when sensitive to the natural cycles of seasons, animal grazing, and crop cycles (Savory, 1988). This view of ecosystem management, called holistic resource management, views people and the environment as a whole.

These examples teach us something about intimacy. Whether biologist, counselor, farmer, or ecologist, they all benefit from a greater appreciation of the temporal complexities within the systems in which they work. By listening to these temporal shapes, the system teaches them how to respond better. In fact, by not imposing their own preconceived temporal framework (e.g., schedules for feeding, mating, crop rotation, counseling), they actually come to participate or interact more with these systems and help them to thrive. After years of studying the relationship between marital interaction and divorce, Gottman (l994b) reached a similar conclusion about how to best conduct therapy with distressed couples. He suggested "Minimal Marital Therapy," where counselors provide couples with repetitive practice of a small set of communication skills and "then hope that a self-guided and self-correcting system takes over after that" (p. 434).

Gottman's research shows that sensitivity to temporal process in intimate relations requires an appreciation of complexity. I believe that for such appreciation, more than one model or definition is required. The scientific tendency toward "the best explanation" or "single guiding theory" may reify a reductionistic, mechanistic, or formulaic viewpoint that is not process-oriented. For this reason, and because this book seeks to stimulate new ideas, I do not provide a single definition of either intimacy or time. However, it may help to know something about how other writers and researchers have defined intimacy and time.

Defining Intimacy

The word intimacy is derived from the Latin intimus, meaning inner or inmost. To be intimate with another is to have access to, and to comprehend, his/her inmost character. In most Romance languages the root word for intimate refers to the interior or inmost quality of a person. The Spanish, intimo, for example means familiar, conversant, closely acquainted. In Italian, intimo signifies internal, close in friendship and familiar, whereas the French intime conveys deep, secret, close, confidential, in German innig means heartfelt, sincere, cordial, ardent, fervent.

(R. E. Sexton and V. S. Sexton, 1982, p. 1)

As Sexton and Sexton suggested, there is a common thread through different definitions of intimacy—an awareness of the innermost character of another person—but there are some differences as well. As Prager (1995) pointed out, an ultimate definition of intimacy is unattainable, partly because it is a "fuzzy" concept, meaning that it is characterized by "a shifting template of features rather than a clearly bounded set" (p. 13, italics added). In fact, it is this shifting, dynamic—what I call catalytic—quality of intimacy that escapes most definitions of intimacy. There is something about the intimate experience that moves us in ways that cannot be neatly defined. Because intimacy is about discovery, it is an "open-system" concept that defies complete definition. Following Prager, this book views intimacy as a superordinate construct, and as multidimensional; it means different things at different times. For scientists, understanding intimacy is a discipline requiring good conceptual tools, careful observation, and an ability to shift from "a clearly bounded set." Intimacy may not be reducible to a specific set of behaviors that occur when two are together, or to cognitions, beliefs, and attitudes about those behaviors. Rather, intimacy occurs as certain catalytic qualities of experience are discovered when individuals participate in knowing another as they know themselves. These catalytic qualities (described in detail in chap. 2) constitute the intimate experience.

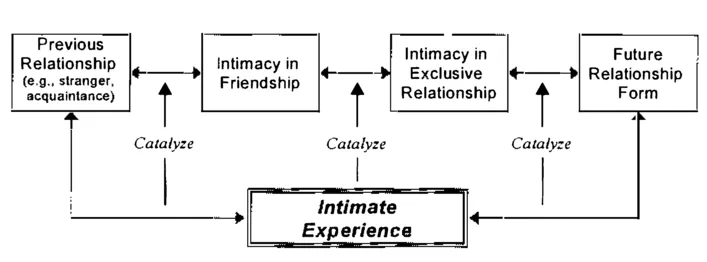

FIG. 1.1. Operational concepts of intimacy.

Measuring Intimacy

Having stated the difficulty in defining intimacy, it helps to present some ways in which scientists have actually measured it. I present three approaches here and the interested reader may consult Prager (1995, Table 2.2) for a list of more than 40 different measures assessing some aspect of intimacy or intimate relationships. Tzeng (1993) also provided a number of actual scales and showed how they are related and distinct from scales that assess love. Each of the following approaches also show how intimacy is alternatively defined as an attitude, a relationship, and as an experiential state. People can experience attitudes and initiate behaviors toward friends that make those friendships more intimate than others (Sharabany, 1994). As those friendships become more intimate, they may turn into more exclusive, partner, marital, or sexual relationships (Garthoeffner, Henry, & Robinson, 1993). Sometime in the development of this intimate bond, individuals may experience a deep personal sense of intimacy (Register & Henley, 1992) that either leads to the intimate friendship or exclusive relationship, shifts the nature of the relationship, or to some other possibility. Thus, intimacy may be experienced as a state, as a process, as a quality of a relationship, or as all three at different times. Figure 1.1 integrates these different operational conceptions of intimacy.

Thus, we may experience intimacy as part of or within a variety of relationship forms (a previous relationship, a friendship, an exclusive or sexually committed relationship). The experience of intimacy may even give the relationship its form and distinguish it from other relationships. Conversely, different relationship forms can stimulate, shape, and mellow the intimate experience. It is also possible that the intimate experience is a critical catalyzer that moves a relationship from one form to another. An intimate experience may move an acquaintance relationship to an intimate friendship, or an intimate friendship may become exclusively sexual through some intimate experience. The following research reflection shows ways in which scientists have tried to capture these different aspects of intimacy. With these and other research reflections, consider whether the questionnaire statements apply to you.

Research Reflection 1

Intimacy in Friendship

Sharabany (1994) developed the Intimate Friendship Scale to study intimacy in the friendships of children and preadolescents, but the items also apply to adult friendships. This scale has eight different dimensions. The following is a list of the major factors and some exemplary or paraphrased items.

Frankness and spontaneity: I feel free to talk with him or her about anything.

Sensitivity and knowing: I can tell when he or she is worried about something.

Attachment: I like him or I feel close to him or her.

Exclusiveness: The most exciting things happen when we are alone together.

Giving and sharing: I offer him or her the use of my things.

Imposition: I am sure he'll (she'll) help me whenever I ask.

Common activities: I like doing things with him or her.

Trust and loyalty: I know that whatever I tell him or her is kept a secret.

Interpersonal Relationships

It is important to point out that not all relationships are intimate and that not all intimate experience occurs in a relationship. Individuals may be married for years and not feel any intimacy, and many people experience intimacy only in solitude or through nature. Interestingly, the features measured by Sharabany overlap with various qualities measured in a more general assessment of adult interpersonal relationships. Garthoeffner et al. (1993) tested the reliability and validity of the Interpersonal Relationship Scale, first developed by Guerney (1977). Whereas it does not refer to the psychological construct of interpersonal intimacy, any individual who experiences most of the factors described in this scale could be experiencing intimacy. The following is a list of the major factors from this scale and some exemplary items:

Trust: There are times when my partner cannot be trusted. (Reverse scored)

Self-Disclosure: I tell my partner some things of which I am very ashamed.

Genuineness: My partner is truly sincere in his/her promises.

Empathy: I feel my partner misinterprets what I say. (Reverse scored)

Comfort: I seek my partner's attention when I am facing troubles.

Communication: I can accept my partner even when we disagree.

There are some subtle but noticeable differences with the previous measure. There may be differences in how intimacy is experienced in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. I encourage those interested in understanding developmental aspects of intimacy to read Prager'...