- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Resource Focused Therapy

About this book

For some time the family therapy field has been moving away from a problem-based approach to work with clients. Ideas such as "creating a new family story", focusing on strengths and solutions, and making contracts with family members have all shifted interest toward a new approach to therapy. The authors have been in the forefront of this thinking for several years and they have been experimenting with their ideas by working together with clients in order to create their own coherent, effective model for therapy. Resource Focused Therapy is the result!

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Introduction

Resource-focused therapy (RFT) is a practical approach to working with people who complain of difficulties, dilemmas, impasses, and problems. It is based on paying the least amount of attention to problems that have become pathologized. RFT strictly focuses on bringing forth the natural resources of both clients and therapists. By "resource" is existentially meant any experience, belief, understanding, attitude, event, conduct, or interpersonal habit that contributes to the positive contextualization and realization of one's being. In its ideal form, RFT does not even appear as therapy; it aims to appear more as the performance of a conversation that engages both therapist and client in transforming their situation from one that is impoverishing to one that is resourceful.

RFT differs from most therapies in that it discounts the metaphor of both "therapist" and "client". We prefer seeing both parties as caught in the same dilemma: how can each be resource-ful to the other? What must the "client" say or perform to evoke a response from the "therapist" that will be resourceful to the "client"? What must the "therapist" say that evokes the "client" to evoke the "therapist"?

More simply put, what must take place to have conversation that is resourceful to all participants? Until the client says something that brings forth the creative imagination (and positive contributions) of the therapist the therapist is in the situation of being treated by the client Both therapist and client are problems until each is transformed—with the help of the other—and becomes resourceful, therapeutic, and healing to the situation.

Our focus is specifically on resourceful contexts. Whether an action, spoken word, or experience is resourceful is determined by the context embodying it. "Resourceful" does not refer to particular events, but to the context of events. A mother's praise for her child is not resourceful on the basis of the words alone, spoken in isolation. Praise is resourceful only when uttered in a context that both perceive as meaningful and positive.

Most of the knots that clients and therapists get themselves into stem from confusion generated by confounding the difference between context and the events being contextualized, A major contribution of Gregory Bateson (1972) was his noting over and over again how different levels of abstraction or understandings are often mixed up, breeding problematic configurations. "Crime is not the name of a simple action" was one of Bateson's favourite paradigmatic examples. The simple action of "shooting a gun" is not necessarily a crime. Crime is the name of a context of simple actions that may include "shooting a gun" or "hitting another person". Similarly, therapy is not the name of a single action. It is the name of a context of actions that often include "appearing at a scheduled time" and "paying a fee".

When the idea that therapy is a context and not a simple action is fully realized, a major shift in understanding takes place for the therapist. It then becomes clear that there are no particular right words, actions, or interventions that will necessarily work for a specific situation. What is called for is the movement of a problematic context into a resourceful context. In a resourceful context, all uttered lines and enacted conduct are contextualized, experienced, and realized as therapeutic.

Without a full commitment to recognizing the meaning of context, therapists will become confused by doing the right thing in the wrong context ("it doesn't work, but it should") or by doing the wrong thing in the right context ("it works, but it shouldn't"). However, with such a commitment, the paradigm of therapy is conceptually quite simple. It involves the transformation of the context within which client and therapist converse.

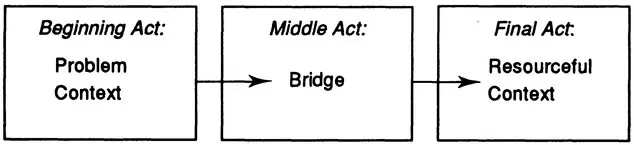

In the beginning of the theatrical play called "therapy", the opening context is often named "the problem". Act I, "the problem", finds a client stuck in the situation where his or her experience is contextualized as "problematic". When a therapist enters the client's problem context, the therapist participates in maintaining it. No matter what is said to the client, whether it be inquiring about the behavioural specifics of the problem, descriptions of attempted solutions, hypotheses about its origin, or professional categorizing and stigmatizing, if it contributes to the theme of the problem then the therapist is potentially helping the client stay stuck in a problem context.

In RFT, the goal of Act I is to get out of it and move into the next one, Act II. In most plays, the middle act is the transformational hinge, linking the beginning to the end. The final act, Act III, is for plays with resourceful endings, a situation of resolution and generativity. This is shown schematically in Figure 1. This diagram, the paradigm of a play, whether therapy or otherwise, is the simplest map available for understanding the structure of therapy.

With this map, therapy involves doing whatever is necessary to get out of the problem context. Again, anything said or done in the problem context, even if it seems the "right thing", is always a potential problem by virtue of its being contextualized as a member of the problematic context. How one gets out of this context is less important than getting out of it. Talking about the world series or fishing or cooking is usually more resourceful than discussing anxiety and depression. The trick, however, is eventually getting into a context where all that is discussed can be contextualized as a resource. Here, what was formerly called the "presenting problem" may now be discussed as a resource.

FIGURE 1

What is never to be forgotten is that therapy does not address problem particulars, but problem contexts. Problem behaviours are not the whole of the problem. The contextualization of any behaviour as a problem is the whole that embraces the problem. This orientation to therapy, previously presented in Improvisational Therapy: A Practical Guide for Creative Clinical Strategies (Keeney, 1991), is rooted entirely in keeping track of the context of one's performance.

In theatrical terms, the name of the scene in which one's lines are articulated must always be kept in mind. Offering help in a problematic or impoverished scene is often not helpful. Creating an opening that helps get you and the client out of impoverished contexts is the first step towards being therapeutic. Getting into and maintaining a constant presence in a resourceful context is the final act of therapy.

Resource-focused therapy is concerned with getting clients and therapists into a resourceful context as quickly and efficiently as possible. If it is possible to ignore the problem completely, this may be done. If the problem must be exaggerated to break into another scene, this may be encouraged.

Focusing on getting into and staying in a resourceful context requires minimizing other actions and understandings previously associated with the profession of therapy. In teaching RFT, trainees are encouraged to pretend that they are not therapists and that they have forgotten all their training, explanatory metaphors, and prescriptions for how to be professional. They are invited to be experimental performance artists, imaginative conversationalists, rhetorical consultants, or simply someone who uses and understands less professional understandings and acts more towards creating a context of resourceful experience.

Historically speaking, RFT is rooted in the genre of therapy called "Brief Therapy". Brief Therapy is rooted in Sullivan's "Interpersonal Theory" (1953) and was elaborated after his death by one of his students, Don D. Jackson. Sullivan was one of the first to insist that it makes no sense to talk of a self and its strivings separate from the interpersonal relations nexus of which it is part (Mullahy, 1967). First as a member of the Bateson research projects on paradox in communication (Bateson, Jackson, Haley, & Weak-land, 1956; Jackson & Weakland, 1961), and later in the Conjoint Family Therapy Model pioneered at the Mental Research Institute (MRI), which he founded in 1959, Jackson and his colleagues laid many of the foundations for Brief Therapy (Ray, 1992b). These pioneers did not work in isolation. They studied and were influenced by many of the leading therapists of their time, particularly the prodigious hypnotherapist Milton Erickson (Erickson, Haley, & Weakland, 1959; Haley, 1967).

The birth of one of the most influential brief therapy orientations was associated with the classic text written by three of Jackson's colleagues at the MRI—Paul Watzlawick, John Weakland, and Richard Fisch—entitled, Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution (1974). They abandoned much of the excessive weight of theoretical psychotherapy baggage to focus on problem definitions and descriptions of attempted solutions. As a therapeutic Occam's Razor, this orientation helped free many therapists to focus on designing imaginative interventions that aim at disrupting the interactional patterns embodying problem conduct.

In a similar vein, Jay Haley (another former member of Bateson's distinguished research team), in his classic contribution, Problem-Solving Therapy (1976), took specific aim at busting problems. Less parsimonious than Watzlawick, Weakland, and Fisch, Haley preferred a more elaborated mythology to account for the occurrence and persistence of symptoms. Influenced by his colleagues Minuchin and Montalvo, he developed a sociological map for contextualizing symptoms in terms of coalitions, hierarchy, and social power. To Haley's credit, a rigorous formal theory was never built. Instead his text loosely drew on simple heuristics and generalizations that aid the therapist in focusing in a specific way on alleviating "problem-in-social-sequences".

The potentially problematic catch in the work both of the Weak-land, Fisch, and Watzlawick team and of Haley concerns their focus on the problem as the theme of therapy. Although their intention is to free the social system from being organized by a problem, their focus on the problem carries the risk that the therapist may contribute to maintaining presence in the problem context.

The work of de Shazer (1982, 1988), a student of Weakland, emphasizes solutions—the necessarily implied and complementary side of all problems. Here a de-emphasis is placed on problems per se and an effort is given to search for solution conduct. The potential problem with this approach is that a focus on solutions does not necessarily remove one from the problems they are supposed to solve.

To focus on either problems or solutions is to remain contextualized within the whole distinction of problems/solutions. The two are inseparable, and one side brings forth the other. As Fisch, Weakland, and Segal (1982) demonstrate, problems bring forth attempted solutions. Blocking the type of class or attempted solution is for them the efficient, although roundabout, way of alleviating the problem. For de Shazer and other solution-focused therapists, a focus on solutions brings forth—whether spoken about or not—problems. A potential disadvantage for both problem-focused and solution-focused therapies is that they each risk holding the theme of therapy in Act I, the context called "problem". In this context, both right and wrong solutions risk remaining a way of preserving the problem context.

Therapists who attempt to learn problem- and solution-focused therapies have too easily overlooked the context within which problems and solutions are discussed. These orientations tend to have a behavioristic feel to them that may seduce the therapist into looking at bits of action or sequences of action without regard to the context of rhetoric giving it meaning.

The contribution of the Milan approach to systemic family therapy, particularly the work of Cecchin and Boscolo (Boscolo, Cecchin, Hoffman, & Penn, 1987; Cecchin, Lane, & Ray, 1991, 1992, 1993), helped correct this deficiency in contextual vision. Their approach radically emphasizes the contexts of meaning (see Keeney & Ross, 1992). At the same time, being influenced by the theoretical ideas of coalitions, paradox, and so forth, this orientation also sets up the potential to fall into the trap of maintaining a focus on the problem/solution distinction, particularly with its focus on "the problem is the solution".

This reversal of the Watzlawick, Weakland, and Fisch slogan, "the solution is the problem", is half of the whole distinction: (the solution is the problem/the problem is the solution). Either side implies the other and maintains the whole theory of being in a universe of problems, solutions, problem solutions, and solution problems.

As part of this historical tradition of brief therapies, our work has naturally developed out of our understanding and practice of the contributions of Bateson, Sullivan, Jackson, Weakland, Fisch, Haley, Cecchin, and Boscolo, among others. What we bring to the theoretical table is an identification of what all these approaches seem to be after, in spite of the very different metaphors they use to discuss their understanding.

Specifically, the goal of therapy is to get clients and therapists out of problem/solution contexts and into a resourceful context. In a resourceful context the problem can be seen as a solution and solutions as problems. Here, however, the new understanding takes place outside of a problem/solution context.

Problem-Focused Therapy

In illustrative terms, RFT evolved out of the history of brief therapy in the following fashion. Beginning with problem-focused therapies...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- EDITORS' FOREWORD

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Theoretical and procedural maps (and anti-maps)

- 3 Worrying about the coach

- 4 The spell

- 5 The family football game

- 6 A history with voodoo: follow-up with James and Mary

- 7 Training exercises for developing the therapist's creativity and resourcefulness

- 8 After words

- REFERENCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Resource Focused Therapy by Bradford Keeney,Wendel A. Ray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.