![]()

p.1

PART I

Introduction to Victims’ Rights

The first four chapters of this handbook are designed to introduce the reader to the rights of a victim in the criminal justice system. Generally, victims have eight categories of rights. The categories are:

• right to be treated with dignity, respect, and sensitivity;

• right to be informed as to the proceeding in the case;

• right of protection for the victim and his or her family;

• right to apply for compensation;

• right to restitution;

• right to prompt return of personal property;

• right to a speedy trial;

• the enforcement of his or her rights as a victim.

The first chapter in the handbook, Issues in Victim Services, provides a general overview of the treatment and assistance programs for crime victims. Chapter 2 discusses federal legislations on victims’ rights and services. Also included in Chapter 2 is an overview of the victims’ movement in the United States. Chapter 3 discusses victims’ assistance programs and provides suggested reforms that are needed to improve their effectiveness.

Chapter 4 explains the victim–offender overlap, situational and social interactionist theories, as well as social and structural processes. In addition, the chapter looks at the role of life course perspective in the understanding of victimization.

Chapter 5 explains the historical development of victims’ rights from a comparative perspective and identifies and discusses specific issues hindering the implementation of victims’ rights legislation across cultures. The chapter also develops a conceptual framework of the role of victims in the criminal justice system.

![]()

p.3

1

ISSUES IN VICTIM SERVICES

Heather Zaykowski

Keywords

victim services; service utilization; eligibility; service barriers; service delivery; victim blame; service access; victims with special needs

Objectives

After studying this chapter, the reader should understand:

• What are victim services.

• Who is most likely to access and receive victim services.

• Barriers to service utilization.

• Issues with service delivery and victim satisfaction.

• Considerations for victims with special needs.

Introduction

Victim services are a broad scope of assistance programs for victims of crime such as helping victims with filing compensation claims, hotlines, legal aid, counseling, support groups, and financial assistance. Some service agencies specialize in one specific form of support, while others provide more extensive wrap-around services. Although receiving support from policymakers, practitioners, and victims alike, there are a number of important issues regarding victim services. First, despite the scope and nature of services available to victims, very few victims actually seek help from such support agencies. Research has identified a number of reasons why victim service utilization is low including lack of awareness that services exist, an inability to access services, and perceived or actual ineligibility for services offered.

Another key issue is whether victims are satisfied with the services they receive. Although research finds that victims who receive services are generally satisfied, there are some differences in terms of victim expectations and what they actually get, as well as what service providers are capable of providing. For example, although a great deal of funding has been allocated to support victim services, individual providers may lack training and resources to meet victim needs. This chapter will examine the origin of victim services and examine these key issues and more.

p.4

Overview of Victim Services

The Victim’s Rights Movement inspired the creation and growth of victim service agencies. It was inspired by the Civil Rights Movements of the mid-to late twentieth century and converging interests between liberal activists and the conservative “tough on crime” movement during the 1970s and 1980s (Simon 2007). The first victim services were established in St. Louis Missouri, San Francisco, California and Washington DC in 1972. These initial programs emphasized assistance for victims of rape and domestic violence (National Center for Victims of Crime 2016). However, support for services was arguably most widely supported after President Reagan commissioned a task force to document the problems faced by crime victims in 1982. This report provided dozens of recommendations for enhancing support for victims of crime including giving victims greater voice and participation in the criminal justice process and additional funding for victim services (Mastrocinque 2010).

Today, every state has programs available to victims for general or specific types of victimization. Public and private victim services programs receive federal, state, and tribal funding from a variety of sources, but most notably the Crime Victims Fund (“the Fund”), established by the Victims of Crime Act of 1984 (VOCA). The Fund is supported by criminal fines, forfeitures, and donations. However, nearly all funds come from criminal fines. According to a study in 2005, 98 percent of funding was attributed to offender fines. Between 2009 and 2010, $4.1 billion was deposited into the Fund (U.S. Department of Justice 2012).

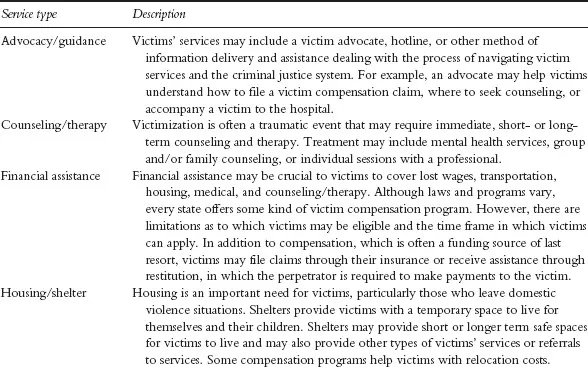

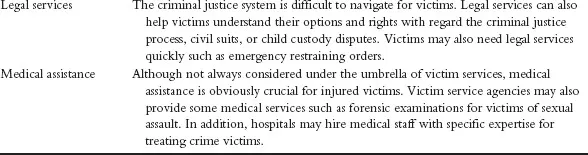

According to the Office for Victims of Crime Online Directory, more than 10,000 victim service programs had been identified through their directory in the United States and abroad.1 Similarly, the National Center for Victims of Crime Resource Center provides a searchable database with over 13,000 service providers.2 Other sources indicate that over 3,000 organizations provide services specifically for domestic violence across the United States and Canada.3 Victim services cover a wide variety of assistance including but not limited to advocacy/guidance, counseling/therapy, financial assistance, housing/shelter, legal services and medical assistance. Table 1.1 provides an overview of the types of services that exist for victims.

Table 1.1 Types of Victim Services

p.5

Barriers to Service Utilization

Few victims actually seek help from victim services despite increasing growth and support for crime victim remedies. In an analysis of data from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), the largest ongoing collection of data on crime victimization in the United States, between 1993 and 2009 only 9 percent of victims of serious violent crime (rape or sexual assault, robbery and aggravated assault) aged 12 and older sought help from services (Langton 2011). Further, only 12 percent of victims who experienced socio-emotional problems sought help from services between 2009 and 2012 (Langton & Truman 2015).

Evidence from state and local studies indicate similarly low contact with service agencies (Campbell et al. 2001; Fugate et al. 2005; Henning & Klesges 2002; Keilitz et al. 1997; Sims et al. 2005; Ullman & Filipas 2001). In a telephone survey of Pennsylvania residents who had experienced victimization in the past 12 months, Sims et al. (2005) found that only 3 percent of crime victims reported using victim service programs. Keilitz and colleagues (1997) found that among women seeking protection orders, one third received assistance from community services, with fewer receiving services from counseling (12.6 percent), private legal services (11.2 percent) and government services (6.3 percent). Among women who were victims of domestic violence, findings by Henning and Klesges (2002) showed that only 14.9 percent of victims sought assistance. While estimates in general remain low, victim services use appears to be higher for rape/sexual assault victims compared with other offenses. For example, research by Campbell et al. (2001) indicated that nearly 40 percent of rape victims received mental health services and 21 percent had contact with rape crisis centers. Ullman and Filipas (2001) found that just over half of victims had contacted mental health counselors and approximately 14 percent sought help from rape crisis centers.

Contact with victim services also varies by demographic characteristics of the victim and the circumstances of the crime incident. A greater proportion of females report that they had assistance from victim services compared to males. Victim services utilization is also greater for those who are older (35 and over) compared with those who are 18 to 24. Victims who are of more than one race, American Indian/Alaskan Native and White (non-Hispanic) received assistance more than other racial and ethnic groups (Langton 2011). Data also indicate that the primary seekers of services are victims of known perpetrators and victims of rape and sexual assault (Langton 2011; Zaykowski 2014).

Low service utilization has led to a growing body of research examining barriers to victim services. Of some of the most prominent limitations, issues include:

• Victims lack of knowledge about services;

• Victims do not want or think they need services;

• Victims lack access to services;

• Victims fear re-victimization and blame by service providers;

• Victims are not eligible to receive services.

p.6

Victims Lack Knowledge about Services or Do Not Want Them

A key reason why victims do not seek services is because they are not clear that such services exist or think that they wouldn’t be eligible for services (Fugate et al. 2005; Logan et al. 2005; Sims et al. 2005). For example, Sims et al. (2005) found that 40 percent of victims stated that they did not know what victim services offered. In another study, one-quarter of women who were victims of domestic violence and sexual assault did not think there were any services available in their community (Zweig et al. 2002). Logan et al. 2005 found that many rural victims lacked knowledge that services existed. This lack of knowledge was propelled by the reality that rape just wasn’t a topic that was discussed in the community. In the same study, urban participants had a misunderstanding about the services available to them. Urban participants noted that the name of services as “trauma” or “crisis” meant that only urgent needs would be addressed (Logan et al. 2005).

Victim awareness of services is shaped by resources available to providers to advertise and referrals. An important link between victims and services are agents of criminal justice. If these individuals do not inform victims that they are eligible for services or that such services exist, victims may never know. Police officers are one of the first contacts a victim has with the criminal justice system and maybe the only one. Therefore, police referrals make them gatekeepers to victim services (Kendall et al. 2009; Zaykowski 2014). Police reporting is also important to obtain specific services. Many victim compensation programs require filing a police report. In one study using data from the NCVS, victims reporting to the police were three times more likely to seek help from victim services. Reporting had the greatest increase in the likelihood of receiving services for victims of intimate partner and family violence (Zaykowski 2014).

Of course, there are also issues and limitations with reporting to the police. Only half or fewer of victimizations of nonfatal violent crimes are reported to the police according to the National Crime Victimization Survey. Reporting rates do vary by type of crime. In 2014 about 60 percent of robbery victimizations and 58 percent of aggravated assault victimizations were reported compared with one-third of rape/sexual assault victimizations and 40 percent of simple assaults (Truman & Langton 2015). Victimizations are more likely to be reported to police when the victim is female, married and older, when the victim is injured, when a weapon is used by the offender, multiple offenders are involved, and the incident takes place in a private location (Baumer & Lauritsen 2010). Relying on police as a service link is particularly problematic for victims of sexual assault who are less likely to report compared with other violent crimes, yet are more likely to cause socio-emotional problems (Langton & Truman 2014). When asked what is the most important reason why they did not report to the police, victims of violence stated that they dealt with it in another way or considered it a personal matter (Langton et al. 2012).

It’s possible that the reasons why victims do not report to the police are the same as why they do not seek help from services (Stohr 2005). Victims may simply not be interested in services (Stohr 2005; Sims et al. 2005; 2006). Victims who previously sought help f...