![]()

Part 1

Leading

INTRODUCTION

The first part of this book contains a lot of material on leadership in the public sector. Some of the questions addressed in these early chapters are very basic:

1 What is expected of leaders?

2 How do strategic leaders relate to employees in the public sector?

3 How do leaders operate as strategists?

Some of the complexity of the literature on leadership – either generally or in the public sector specifically – arises because very different motives inspire those who write about leadership. It is by no means all strictly focused on understanding what leaders do and what the consequences of leadership are. Some people write because they are intrigued by the ideas and concepts of leadership. Some are idealists and probably wish there was no need for leaders.

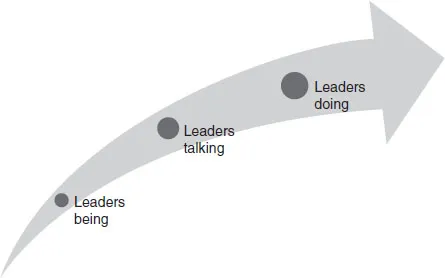

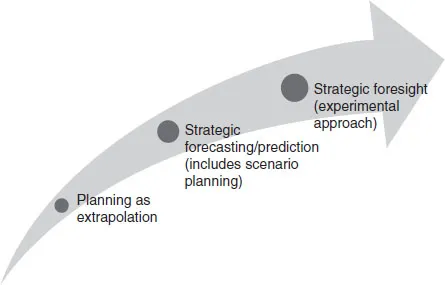

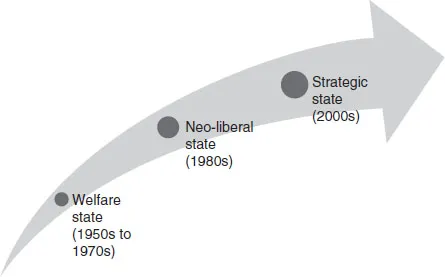

Some of the complexity is simply created by the passage of time and the changes and movements in the aspects of leadership selected for attention (Figure P1.1), the leadership techniques that have come to the fore (Figure P1.2) and the context of leadership (Figure P1.3).

Figure P1.1 Changing aspects selected for study

Figure P1.2 Changing techniques used by leaders

Figure P1.3 Changing context

![]()

Chapter 1

What is expected of leaders?

■ To consider some influential ideas of leadership

■ To consider what others expect of leaders in the public sector

■ To appreciate that strategic leadership is not about infallibility

■ To know and understand a working definition of strategic leadership in the public sector

INTRODUCTION

Leadership in the public sector shot to prominence just as the new millennium arrived. It had become a ‘hot issue’ in the public sector (OECD 2001). The buzz around leadership at this time coincided with a new wave of public sector reform occurring in a number of countries. The 1980s wave had begun shifting the public sector from a culture of ‘administrators’ and ‘policy’ to that of ‘management’ and ‘efficiency’. The new 1990s wave of reform seemed spurred by a heightened concern for the effectiveness of the ‘state’. It seemed that this was a time for leaders rather than managers (or administrators) because there was a need for change agents who could transform organizations and institutions. Bichard (2000: 44) made the case for leadership rather than management in these terms: ‘Yet it is leadership that we need … because it is leadership and not good management that transforms organizations’.

The World Bank’s advocacy of reform of the state, apparent in the mid 1990s, not only entailed calling for effective leadership but also for farsighted leaders, for leaders who put forward long-term visions, and for leaders who built coalitions and encouraged a wide sense of ownership of reform agendas. The World Bank was talking about politicians as leaders of reform (World Bank 1997: 14):

Reform-oriented political leaders and elites can speed reform by making decisions that widen people’s options, articulate the benefits clearly, and ensure that policies are more inclusive. In recent years farsighted political leaders have transformed the options for their people through decisive reform. They were successful because they made the benefits of change clear to all, and built coalitions that gave greater voice to often-silent beneficiaries. They also succeeded – and this is crucial – because they spelled out a longer-term vision for their society, allowing people to see beyond the immediate pain of adjustment. Effective leaders give their people a sense of owning the reforms – a sense that reform is not something imposed from without.

The 1990s was also a period when thought was given to how leaders could be developed in the civil service. In 1996, a newsletter of the Public Management Service of the OECD, which existed to report and assess new developments in public management, contained a reference to a public sector MBA (PUMA 1996: 5):

The public and private sectors are coming closer together. We are operating in the same economic and social environment. Future senior civil servants need to understand this environment and its changing pressures in just the same way as future leaders of industry. The mutual exchange of skills and information through initiatives like the Public Sector MBA is a major element in this process. A professionally qualified civil service will be able to continue to meet the changing demands placed upon it.

While a connection between the reforms in the public sector and leadership was clearly and strongly articulated just as the new millennium arrived, it now sometimes seems that our understanding of public sector leadership often takes as its starting point the ideas of American writers and researchers, some of whom were largely thinking about the 1980s and the private business sector of the US. By way of explanation for this US influence we can note two claims made by Bass (1997: 131); first, that the world’s language of business is English; and second, that ‘much of American management practices and management education have been adopted universally’. The second claim may be an exaggeration, however there is no doubting that US ideas about private sector business leadership have had widespread and persisting influence on the thinking of academics and practitioners in many countries.

SOME INFLUENTIAL AMERICAN IDEAS

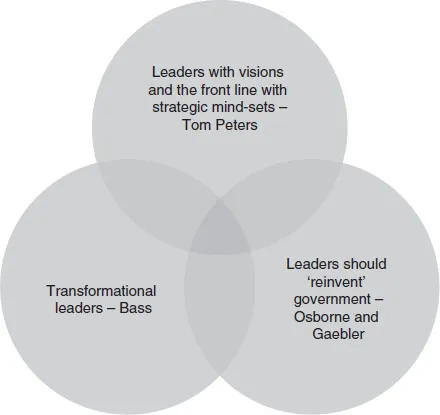

Tom Peters wrote about business leadership in a period he saw as defined by fast-pace change and by complex environments. Bernard Bass was the most important writer on transformational leadership. David Osborne and Ted Gaebler used public sector experiences in the US and elsewhere to suggest that public sector leaders should change various things and thereby create entrepreneurial government, which they considered was emerging, and should emerge, from a bureaucratic phase of government. The following sections expand on the ideas of Peters, Bass, and Osborne and Gaebler (Figure 1.1) and are intended to provide a useful background of knowledge and thinking to more recent ideas of leadership in the public sector covered throughout the book.

Tom Peters

Peters, in Thriving on Chaos (1987), presents himself as an intellectual revolutionary and claimed that his book would challenge everything people thought they knew about managing. A revolution in management was needed because of the business environment (Peters 1987: 45): ‘Today, loving change, tumult, even chaos is a prerequisite for survival, let alone success’. He said predictability was a thing of the past. In fact, at one point he said (Peters 1987: 9), ‘Nothing is predictable’. Businesses did not know from day to day what the energy prices would be, what the price of money would be, who their competitors would be, where the competitors would come from, and who would be partnering with whom. Businesses faced uncertainties about technology, about consumers, their tastes and their preferences. The strategies of business organizations were constantly changing (Peters 1987: 8): ‘Strategies change daily, and the names of firms, a clear indicator of strategic intent, change with them’.

Figure 1.1 Influential perspectives

Not surprising in the light of all this, he rejected the possibility of anticipating the future through forecasting (Peters 1987: 11):

Sum up all these forces and trends, or, more accurately, multiply them, then add in the fact that most are in their infancy, and you end up with a forecaster’s nightmare. But the point is much larger, of course, than forecasting. The fact is that no firm can take anything in its market for granted.

Peters said that businesses could be highly successful one year and within just a few years be in difficulties. It might be inferred from this that he was linking change and external volatility to precariousness and threats to the success and survival of businesses.

In the face of all this change and complexity, what should business leaders do? He said they should thrive on this chaos. He wanted businesses to be quick – we might now describe this as ‘agile’. Businesses had to react quickly to market opportunities that were short-lived because of all the change occurring. This was to be done through more informality and as a result of front-line managers being at the heart of deciding the future direction of a business. He championed experimentation, with experimentation initiated by the front-line of management, rather than company headquarters (Peters 1987: 390):

Each day, each manager must practically challenge conventional wisdom…Since new truths are not yet clear, the manager must become ‘master empiricist’, asking each day: What new experiments have been mounted today to test the new principles (in the market, in the accounting department, etc.)?

Business organizations were to experiment, learn, seek change and adapt. ‘The organization learns from the best, swipes from the best, adapts, tests, risks, fails, and adjusts – over and over’ (Peters 1987: 395). He warned businesses against seeking stability and predictability. He said (Peters 1987: 395), ‘Nothing can be “institutionalized”’. Change was constant.

He wanted businesses to focus on developing their skills and capabilities so that they could be flexible and quick in reacting to market opportunities. This concern for skills and capabilities may put us in mind of the resource-based competition model proposed by Hamel and Prahalad (1994), but it should be noted that they took a very different view from Tom Peters on how to address the future. They believed that experimentation should be steered towards an industry foresight – it was not the almost random experimentation favoured by Peters.

Reading between the lines, Peters was not a fan of leaders in the corporate headquarters. Top leaders, as far as Peters was concerned, should concentrate on establishing a framework for front-line management to exercise their initiative. The top managers were to develop visions and values. They were to develop clear visions so that experimentation, testing and risking would be stimulated. He suggested that the experiments and risking might change the vision, so the vision was not to be driven by the top leaders come what may. The visions served the experimentation. It was, he argued, a new type of control, different from the control exercised through a hierarchy of bureaucrats. Leaders would experience corporate life as being far from totally and perfectly controlled by the centre (Peters 1987: 395):

[Leaders] must preach the visio...