- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Perspectives on Supervision

About this book

This reader-friendly and stimulating volume, indispensable to anyone interested in supervision from a systemic perspective, emerged from a conference organised jointly by the Institute of Family Therapy and the Tavistock Clinic in London. It is focused on developments within supervisions and reflects the increasing need for clinical supervisors in advanced level family training courses. The central theme of the book is the application of systemic thinking to the field of supervision. The complexities of topics involved in this area are fully engaged by the many contributors. The book is organised into four main sections, each ending with a useful and unifying commentary from the editors.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

SETTING THE CONTEXT FOR SUPERVISION

CHAPTER ONE

Different levels of analysis in the supervisory process

I see supervision as a generative and transformative process—that is, as a process through which people develop abilities and skills. Before I present my ideas on supervision, however, some distinctions need to be made. The first section therefore outlines some theoretical specifications based upon which, in the later sections, I reflect on the different models of supervision.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Constructivism and constructionism: a both/and vs. an either/or perspective

Over the past decade, the systemic approach to psychotherapy has been much influenced by the constructivist and constructionist perspectives.

•Constructivist perspective. From this point of view, people make sense of their own experiences and act in relation to others according to a set of premises and beliefs. To put it more precisely, the actions and responses of people to the behaviours of others are a function of: (1) their individual systems of representations; (2) the meanings they attribute to behaviours and events according to their representational system(s); and (3) the type of responses that they intend to have from others. This set of premises and beliefs, or system of representations, comes from: (a) the specific position that people have in the interactive situation, (b) the experiences lived prior to the given interaction, and (c) the experiences that people are presently having within multiple relationships in several different social contexts.

In other words, people make sense of their world through a set of premises and beliefs, and this representational system is generated through interactive processes. It should be noted, though, that the constructivist perspective stresses overall the processes through which people construct their worlds and not the interactive processes through which beliefs are generated. The works of Von Foerster (1981), von Glasersfeld (1984), and Maturana and Varela (1980) have contributed to directing the attention of systemic therapists to the role that cognitive processes have in constructing reality.

•Constructionist perspective. Constructionists criticize the constructivist perspective as being too much centred upon the individual. The works of Gergen (1988), Harré (1989), and Shotter (1990) have all contributed to shifting the attention of systemic therapists away from cognition and towards language as the main process through which social worlds are generated. According to these authors, the emphasis on cognition hides the social nature of the process of constructing realities. Meanings, they claim, are not individually constructed. It is through communication and language that the participants of interactions negotiate the meanings of events and behaviours; they co-construct personal and social identities and co-define roles and relationships. In other words, they interactively generate and develop specific ways of organizing the world in which they live. Constructionism focuses on the social processes of constructing meanings.

The constructivist and the constructionist perspectives are usually considered as being oppositional, polarized stances within the field of systemic therapy. I, however, do not see these two perspectives as being in opposition; instead, I view them as being intertwined. Moreover, I see them as descriptions of different levels of the complexity of interactive processes.

The constructivism/constructionism polarization reflects, in my view, other polarizations such as cognition and communication (or language), individual and relationship, semantics and pragmatics, observed and observing systems, meanings and actions. But, as suggested by Varela (1979), these polarities can either be seen as distinctly separate and opposite entities or be considered as embricated entities. The term “embricated” implies that while the entities are different and irreducible one to the other, they nevertheless emerge one from the relationship with the other. Whether we see them as opposite or as embricated/connected entities depends on the perspective we take. If we take a both/and approach instead of an either/or approach, we can see that the polarities of the couple “constructivist and constructionist perspectives” are connected. In fact, from a both/and perspective, we can describe any interactive situation at a double level—at the level of individual construction and at the level of co-construction—and the two levels are intertwined.

When we choose to describe the level of individual construction involved in an interaction, we focus on how people take part in interactive processes. From this perspective it is possible to point out the ways in which people make sense of their world(s), including themselves, others, and the situations they cope with. It is also possible to point out how people act both according to the way they make sense of all this and in the pursuit of maintaining an equilibrium between all the different components of their own reality. So, when we describe the individual level of construction, we point out how people take part in interactions and we stress feelings, meanings, goals, and behaviours. We may also underline how behaviours are connected to feelings that are connected to meanings, which in turn are connected to behaviours that are connected to goals.

But while the participants in the interaction are engaged in these complex symbolic, behavioural, strategic, and self-validating processes, they also initiate a “dance”—which we can call coordination of behaviours, joint action, language game—through which they negotiate and co-construct meanings, identities, relationships, roles, and social realities. When we choose to describe this joint process, we point out the level of co-construction. From this perspective, we do not underline how people take part in an interaction; rather, we focus on what they do together.

The level of co-construction and the level of individual construction are linked through a recursive process. If we read the recursivity beginning from the level of co-construction, we can say that social interactions generate meanings and realities through which individuals define themselves and participate in interactive processes. But the same recursivity can be described starting from the individual level of construction: individuals are co-authors of a coordination of actions and meanings which gives shape to a social interaction through which individuals process are generated (Bateson & Bateson, 1987; Maturana & Varela, 1980; Moscovici, 1989).

The level of individual construction is stressed by constructivism, and the level of co-construction is emphasized by constructionism. These two perspectives can be combined and result in a complex point of view that guides us in the analysis of the interconnection of individual and relational constructions involved in any interaction. When people start an interaction, they bring with them other interactive stories that have generated specific meanings and social realities. It is from these previously constructed social realities that people engage in new interactions and give shape to a dance through which they co-construct new meanings and new social realities. As Karl Tomm puts it, “‘Outer’ interpersonal conversations become ‘inner’ intrapersonal conversations (in the form of conscious awareness and thinking) which support further outer conversations that modify inner thought, and so on” (Tomm, et al., 1992, pp. 117–118). It should be noted, though, that social interactions do not always construct change. Through social interactions, people might re-construct or perpetuate meanings and realities.

Levels of descriptions of the therapeutic process

The distinction between the individual and the co-construction levels of interaction is helpful when distinguishing between different levels of analysis of any therapeutic situation (Fruggeri, 1998).

At one level (individual construction) we focus on the therapist: on his or her thoughts, intentions, decisions, and language. We could, of course, have talked of goals, descriptions, ideas, and theoretical models—or even of prejudices, values, ideology, and actions. At the individual construction level of analysis, we pay attention to how all these elements connect with each other in a pattern that could be defined as “the way the therapist participates in the interaction with the client”. Most conversations among therapists take this level into consideration—that is, the level of reflexivity between theoretical framework, attribution of meaning (descriptions), and actions. It is according to a theoretical model that therapists describe the situation as they do, and it is according to what they describe and to their theoretical model (or to their philosophical stance) that they make decisions to do this or that in order to help the client. It does not matter whether the theoretical framework is informed by social constructionism (e.g. the therapist decides to take a “not-knowing position”) or whether the theoretical framework is strategic (e.g. the therapist decides to give a paradoxical prescription). In both cases, the therapeutic actions (which should not be confused with the therapeutic effects) emerge from an individual construction.

Of course, therapists are not the only ones who individually construct and act in the situation. Clients are engaged in the same kind of process. Therapists who have collected descriptions of how their clients viewed therapies have found interesting points for reflection. Here is an example:

We had great expectations from that psychotherapy, and at the beginning things seemed to go very well: we all liked the doctor. He started by saying that first of all we had to picture the situation. But then, that picture was never ending…. He used to make us talk, talk, talk…. We were willing to do anything in order to change something…. We never talked about Luciano’s problems … mainly of the past…. But Luciano was getting worse and worse. We expected the doctor to give us advice on what to do. We asked him questions, but he used to tell us to turn those questions to each other. Instead of answering questions himself, he was asking us questions all the time. Every once in a while he tried to make us see the positiveness of our situation, and that there wasn’t much to change. We started to feel … I don’t want to say cheated, but we started to feel not helped. [Cingolani, 1995, p. 117]

Clients do not have formal theoretical models to refer to; they have naive or implicit theories according to which they also make sense of what is happening and then act. Clients do not respond to the therapist according to what the theoretical model of the therapist states; they respond according to the sense they make of what the therapist does—that is, according to their own way of constructing the situation and in order to achieve their own goals, whatever these may be.

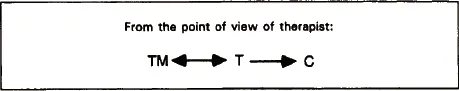

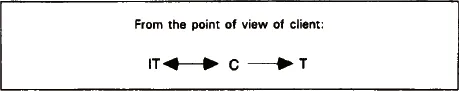

The individual construction level of the therapeutic situation can be described as in Figures 1.1 and 1.2. Figure 1.1 describes a therapist (T) who, according to his or her theoretical model (TM), analyses, listens, explains, invites, makes interventions, and tries to understand the client (C). Figure 1.2 represents a client (C) who, according to his or her implicit or naive theories (IT), makes sense of the therapist and the therapeutic situation and responds to the therapist (T).

While therapist and client are engaged in their individual processes of construction, they also participate together in a cooperative dance, a joint action through which they negotiate and co-construct who they are, what they are doing together, and what the situation is that they are involved in (Pearce & Cronen, 1980).

If the level of individual construction is characterized by self-validation, organizational closure, and recursivity, the level of co-construction is characterized by deuterolearning (Bateson, 1972), structural coupling (Maturana & Varela, 1980), and unintended consequences (Lannamann, 1991; Shotter, 1990).

We could say that any action of the therapist and the client can be reflexively connected to their representations, intentions, and goals, but the outcome (the effect of their actions) is generated through the constructive process in which therapist and client are co-authors, each one starting from his or her own premises and stories.

The co-construction level of the therapeutic situation can thus be described as in Figure 1.3. The focus in Figure 1.3 is on the double arrow that indicates the joint action of therapist and client. The analysis of this level of the therapeutic process does not pertain to the therapists’ ideas or actions, goals or expectations, nor to the clients’ ideas, actions, goals, or expectations. At this level, the analysis implies a description of interactions—that is, of the joint action of therapist and client and of the meanings generated through it.

I consider the distinction between the levels of individual construction and of co-construction to be central, as will be seen particularly when we come to talk about supervision. I also address later on the question of whether supervision deals with the level of individual construction or with that of co-construction. I want to underline here that in order to maintain the distinction between these two levels of interactive proc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Editors’ Foreword

- About the Authors

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part I: Setting the context for supervision

- Part II: Perspectives on training

- Part III: Perspectives on practice

- Part IV: A perspective on evaluation

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Perspectives on Supervision by David Campbell, Barry Mason, David Campbell,Barry Mason in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.