- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Systemic Couple Therapy and Depression

About this book

Based on a research project which demonstrated the effectiveness of systemic therapy, this book can be used as the basis of a training programme in systemic couple therapy, as a phase in the treatment of depression. It describes in explicit detail the range of techniques used and can therefore also inform the next generation of research studies, which will be greatly facilitated by this work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The London Depression Intervention Trial: design and findings

The London Depression Intervention Trial (LDIT: Leff et al., in press) was set up in 1991 to compare the effectiveness of antidepressant drugs, individual cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), and systemic couple therapy. Patients diagnosed as "depressed" by psychiatrists were randomly assigned to one of these three treatment modalities. However, the CBT arm of the trial had to be stopped at an early stage because the drop-out rate was so high (8 out of the first 11 cases). The final comparison, therefore, was between drug therapy and systemic couple therapy and involved 88 subjects who met the research criteria and were taken into treatment.

One of the major findings was that depressed people seen in systemic couple therapy did significantly better than those treated with CBT or antidepressant medication. It was because of these encouraging results for couple therapy that we decided to write this book.

Background of the study

All research projects have their own histories. They come to life in specific contexts, for specific reasons. Julian Leff, professor of psychiatry and an internationally known researcher, has been involved for many years in furthering the understanding and clinical usefulness of the concept of Expressed Emotion (EE) in research on families and persons diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia (Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Eberleinfries, & Sturgeon, 1982). There has been some research support for the hypothesis that EE might be relevant in working with depressed patients and their key relatives. This led to the setting up of the LDIT to determine whether intervening with a family member or partner might have beneficial effects on the designated patient's depressive symptoms if the partner's EE was reduced.

This is where another piece of history comes in. In the mid-1980s, Julian Leff and the Marlborough Family Service team in London, a group of therapists working systemically in a community setting, jointly engaged in researching the outcome of their therapeutic work. EE was used to measure aspects of the couple (dyadic) relationship, and the study showed that EE (and Critical Comments in particular) was reduced in couples and families presenting problems ranging from emotional and conduct disorders in children, to eating disorders, marital discord, and family violence. These results provided further encouragement to investigate the relationship between depression and EE and to determine whether the existence of such a relationship might inform therapeutic practice. Eia Asen was one of the Marlborough team involved in the study (Asen et al., 1991) and was therefore approached by Julian Leff to set up the pilot phase of the LDIT. Elsa Jones joined the project after the pilot phase.

Because cognitive behaviour therapy and pharmacotherapy with a psychoeducational component had already been rnanualized, it was necessary for systemic couple therapy also to be described in a manualized form (see chapter two). No controlled studies had been carried out evaluating whether systemic therapy was of any use with depressed patients. Because no standardized treatments existed, the development of a treatment manual for this form of therapy was a precondition for the funding of the study by the body providing the grant—the Medical Research Council.

Version 1 of the manual was exactly one page long, since it seemed impossible to make concrete the art of therapy. However, this version was not acceptable to the researchers, as it was thought to be "too vague". Version 2 went to the opposite extreme: over 100 pages, narrowly printed, obsessionally detailing every possible therapeutic manoeuvre, with form of words, tone, pace of delivery all prescribed. When trying this out, it emerged that not even the writer of the manual could possibly have any hope of adhering consistently to it. At this point, Elsa Jones joined the project and provided a different perspective. Over a period of nine months, new ideas and techniques were introduced and then modified by both of us until agreement had been reached on a version that we could both subscribe to.

Writing a treatment manual is one thing, but adhering to it is another. Adherence to a manual or protocol is important in research so that results can be compared. It makes it possible to replicate research and to assess whether treatment models being compared are significantly different from one another. Consequently, each session was videotaped, and tapes were randomly selected by an independent rater to check for treatment adherence and treatment integrity. This included looking at fifteen sessions with a total time of 1,026 minutes for CBT, thirty-eight sessions with 1,971 minutes for couple therapy, and forty-seven sessions with 1,445 minutes for drug therapy. This research (Schwarzenbach & Leff, 1995) concluded that it was possible to distinguish clearly between different models. Each model was demonstrably characteristic of itself and not of the other models. It was also found that the therapists adhered to the manual but also occasionally used some techniques from other therapies. Therefore, despite our difficulties in coming to terms with writing a manual, this research demonstrated that it was possible to describe what we did in such a way that the description encompassed our work but did not overlap with that of the other modalities.

The LDIT

Method

The LDIT involved an initial baseline assessment of depressed patients and their partners, followed by an intervention (treatment) phase. Patients were assessed at the end of treatment and again after a twelve- to fifteen-month period of no treatment. The treatment phase consisted of a maximum of nine months or twenty sessions for couple therapy and CBT, and one year for antidepressant medication. Patients allocated to one of the treatments were not permitted to receive any other treatment simultaneously. In other words, those patients seen for couple therapy did not receive any antidepressant or other pyschotropic medication. In the twelve months after completion of treatment, it was permitted to offer a maximum of two booster sessions.

Patients had to meet criteria for depression as measured by the Present State examination, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The threshold for significant depression on the BDI was set at 11. Partners were assessed on the BDI and the Camberwell Family Interview (Vaughn & Leff, 1976), and patients and partners were assessed on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale. The partner had to be rated as expressing at least two Critical Comments (high EE) during the Camberwell Family Interview (Vaughn & Leff, 1976). In addition to these baseline assessments, all patients—and, in couple therapy, also their partners—were given six-weekly BDI assessments to plot the course of mood changes during the treatment phase. Following termination of treatment, three-monthly BDIs were done by the researchers until the follow-up assessment. Subjects were excluded for a variety of reasons, including psychotic features, bipolar illness, organic brain syndrome, and primary substance abuse. The subjects who were included met the psychiatric criteria for significant depressive illness. Patients allocated to the different treatments were matched on all relevant characteristics, such as age of patient and partner, sex of patient, and chronicity and severity of depression. All therapists of the three different treatment modalities (CBT, antidepressant drugs, systemic couple therapy) agreed that the sample seemed biased towards the heavy end of the spectrum, with many of the patients having long psychiatric histories and being significantly distressed and socially disadvantaged. The presence of particularly difficult patients entering research projects is not an unfamiliar finding, and we discuss some of the implications below.

Results

On a number of different measures, couple therapy proved to be more effective and acceptable than antidepressant medication. Patients participating in couple therapy were less depressed at the end of treatment and on two-year follow-up.

Patients receiving antidepressant medication dropped out at a much more significant rate (56.8%) than those in couple therapy (15%). A fuller discussion of the complexity and wealth of data can be found in the research paper by Leff et al. (in press). A health economic analysis showed that antidepressant treatment is no cheaper than systemic couple therapy.

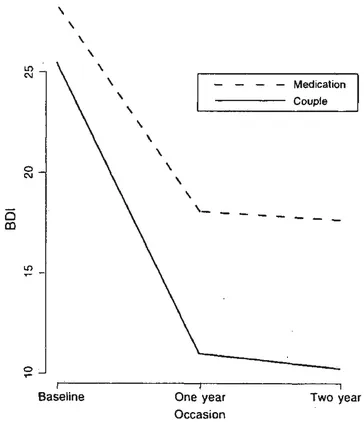

Figure 1.1 Mean profiles of couple and medical treatment groups

Figure 1.1 graphically illustrates the differences between the two treatment modalities as measured by the BDI. It can be seen that on average there is a dramatic drop in depressive symptomatology in the couple therapy group, not only at the end of treatment but, perhaps more strikingly, at two-year follow-up.

What do the findings mean?

The major finding of the study has to be the reduction in depression in the patients receiving this diagnosis. However, a number of other findings seem to us worth discussing.

Expressed Emotion

Did EE change during or after the different treatments? The number of Critical Comments, so crucial in the work with families containing a person diagnosed as schizophrenic, was found not to be related to change. In some of the couples with dramatic reduction in depressive symptoms, the number of Critical Comments went up, in others nothing changed, and of course there were those where there was a reduction. However, there was a significant change in another dimension of EE: the level of Hostility was significantly reduced in the couples' group as compared with the group of patients receiving antidepressant medication. Systemic therapy appears to affect hostility expressed by partners of depressed patients.

The costs of treatments

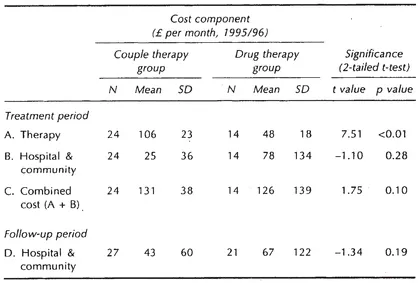

A health economic analysis was built into the research project from the very outset. The cost of couple therapy was calculated on the basis of the average number and duration of sessions (12 sessions, 60 minutes) and the unit cost of direct therapist contact time. All prescribed antidepressants (and associated blood tests) plus the prescribing psychiatrist's time were costed. Service utilization data were collected during therapy and on follow-up, covering a range of key health and social care services (in-/out-/day-patient hospital services; day care; contacts with a GP, community psychiatric nurse, social worker, counsellor, etc). Unit costs were attached to these data and aggregated to give a total cost estimate for each study subject. The mean cost of couple therapy was approximately £100 per session and that of drug therapy about half that, £50. However, it emerged that this significantly greater cost of treatment was offset by a reduction in hospital service use costs (£20 less per month in the couple therapy) and community service costs (£33 per month less). In summary, the combined cost of therapy and service turned out to be similar for the two groups (see Table 1.1).

Table 1. The costs of therapy and service utilization

We would like to speculate that the economics of working systemically might be even more striking than emerges from this analysis. First of all, many patients receiving antidepressant medication outside of research projects continue with the drugs for years. Therefore, the long-term costs of prescribing antidepressant medication would in reality be higher. Furthermore, this study did not cost for informal caregiver support by family or others, or for the indirect consequences of depression, such as lost employment. Again, this means that the actual economic benefits of no longer being depressed are greater than can be captured in the health economic analysis undertaken.

The subjects

It is striking that of the 290 individuals with whom the research initially made contact, 196 were excluded for a variety of reasons (no stable relationship, not being depressed, not being willing to accept randomization). Of the 94 taken into the trial a further 6 subsequently rejected the possibility of accepting antidepressants were they to be allocated to the medical arm of the study. Furthermore, for reasons of statistical simplicity, only heterosexual couples were considered.

Again, we venture to speculate that this process of repeated selection and self-selection resulted in a particular group of patients crossing the hurdles into the final stage of being accepted for therapy. What does it mean for a patient—or a referrer on behalf of a patient—to agree to accept any of three very different types of treatment to which they know they will be allocated at random? Most people have some opinion on what might be helpful in addressing their difficulties. To accept the conditions of the study probably means that one has given up hope for oneself or for one's referred patient. This must then have implications for the bias observed by the therapists—namely, that patients tended to belong at the more serious end of the spectrum. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why CBT seemed inappropriate for this group of patients, given that it has established itself as a suitable treatment for depression of recent onset and short duration.

The relatively low drop-out rate in the couple's group has been explained by the researchers as probably due to the greater acceptability of this approach when compared with antidepressant medication. This may well be valid but we think there could also be other reasons. In the first place, when we first met them, many of the partners of the patients diagnosed as depressed expressed their reluctance to participate in therapy (see chapter five), and we had to work hard to facilitate their engagement in the work. This is something that systemic therapists are particularly good at since, from the very beginnings of family therapy, we have set ourselves to learn how to involve family members, who may be reluctant to attend, in a cooperative endeavour focused on the resolution of problems that might at first be seen as being located within an individual. Second, systemic therapy—unlike some other therapeutic approaches—does not have a fixed procedure but works interactively, responsively, and reflexively in relation to the presentation of the client(s). This probably influences the quality of engagement. Third, systemic therapists are always interested in the wider system that forms the context for the symptom and its carrier. This interest may take the form of inviting significant others to sessions, in person or metaphorically, which signals the therapist's conviction that problems and their solutions may be located in the context rather than solely within the client. This context might mean the immediate interpersonal system of the designated patient or the wider context of culture, employment, and so forth. These ideas are explored in more detail in the subsequent chapters, but we mention them here because they may well constitute an explanation for the "acceptability" of systemic couple therapy.

Experiences in this project showed that it is possible to work within a positivist scientific framework without having to compromise the systemic stance. The results when viewed within the dominant scientific discourse prove that systemic couple therapy with depressed patients is effective. We have also found as psychotherapists that it is possible to survive and learn from participation in such a research project.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- Contents

- NEW FOREWORD

- SERIES EDITORS' FOREWORD

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- OVERTURE

- CHAPTER ONE The London Depression Intervention Trial: design and findings

- CHAPTER TWO The therapy manual

- CHAPTER THREE Working with depression, I

- CHAPTER FOUR Working with depression, II

- CHAPTER FIVE Themes and variations

- FINALE

- REFERENCES

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Systemic Couple Therapy and Depression by Eia Asen,Elsa Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.