CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Creative writing and historical context, research and teaching

Chapter contents

The fairytale of authors in schools

History of creative writing in schools

Creative writing – process or product?

Creative writing – contemporary practitioners

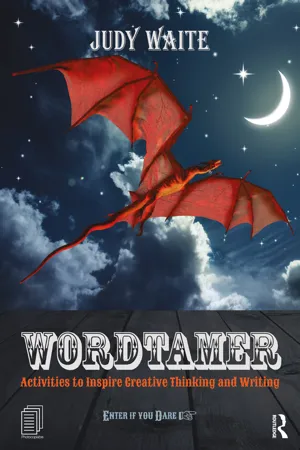

Wordtaming and the funfair of ideas

Spelling, punctuation and grammar – pupils who struggle

Ofsted observations – evidence and research

Gender differences in creative writing

Boys versus literacy

Storytelling versus story writing

Creative writing and ICT

Blended learning

Blank in the mind

Fiction versus non-fiction

Research and imagination

Interactive writing approaches

(VARK)

Can creative writing be

taught?

Creative individuals, universal

approaches

Author practice

Writing in education – from reception years to MA and PhD

Moral messages evolved through

fiction

Writing for experience

Writing original material

Craft skills and raising standards

Why do stories matter?

The value of stories

Morals and writing

Complex thought and discussion (scope for)

Fairytales and cultural influences

Themes and messages

The fairytale of authors in schools

When I was first published as a children’s author, writers were often seen as celebrities in schools. We were invited in to talk about recent books, describe a typical writing day, divulge the mysterious secrets of where we got our ideas and explain the intricacies of the publishing process. We answered questions, sold books and wrote our signatures on the prelim pages with an elaborate flourish.

I was never altogether comfortable with this model. It seemed to be a day when the waters parted; the author rose up from mysterious depths, then later sank back into their watery otherworld. These authors left no discernible traces in the halls of learning. They could only hope that perhaps, sometimes, pupils found a shell, or the bones of small fish, and grew curious about where they’d come from.

I became more interested in exploring approaches that might still resonate once my visit was over. I wanted to investigate how my own creative writing techniques might work even if I wasn’t there to facilitate the activity. Consequently, I created bespoke sessions for differentiated activities and outcomes and included extension activities that could run beyond my sessions. Feedback from these was always positive and was often particularly remarkable around pupils who had previously been working at ‘below average’ in terms of focus, imagination and written outputs.

I was not the first to be thinking like this – it was just that this was the first time I had thought like it.

Creativity, creative process and links to literacy are on a journey that can be traced back to the 1960s and doubtless before that. Educationalist Sir Alec Clegg wrote The Excitement of Writing (1964), drawing from peers who were combining art and music to inspire young writers (Jones and Wyse, 2004: 21). The book included samples of pupil work that demonstrated impressive results, and Clegg evolved material that was critical of the divide between mind (something measurable) and spirit (something felt). He articulated this by comparing the differences between writing on a prescribed topic from notes on the blackboard and telling someone in your own personal written words of something that has excited you (Clegg, 1972).

The notion of creative writing as a ‘process’ rather than a product, attributed to Donald H. Graves, emerged in the 1980s and Graves went on to establish the practice of writing workshops in schools. Writing workshops became embedded within literacy teaching, creating a ‘community of writers’. Teachers and pupils wrote alongside each other, creating and sharing ideas and techniques (Chamberlain, 2016). Lucy McCormick Calkins (1994) continued evolving craft approaches alongside writerly practice, acknowledging that ‘writing does not begin with deskwork but with lifework’.

Since the turn of the century there has continued to be an impressive flow of innovative pioneers. Talk for Writing (Corbett, 2011) takes a collaborative approach: young writers listen to the rhythms and cadences of language in advance of writing their own stories, and teachers share writing practice with their class, evolving and improving ideas through purposeful discussion and example. The National Association of Writers in Education (NAWE) placed writers in nine different schools between 2006 and 2009, visiting once a term over the course of three years and demonstrating measurable progress in the literacy and writing skills of the control groups they were assigned to (Horner, nd). Schools, recognising the impact professional writers could make to the written work of pupils (Cremin and Myhill, 2012: 157–8), brought in writers who would attach to the schools for longer periods, as consultants and as writers-in-residence.

Teresa Cremin, former president of the United Kingdom Literacy Association (UKLA) and Professor of Education (Literacy) at the Open University, has conducted a range of studies and interactive literacy initiatives including schemes that challenge traditional approaches to reading, and has also developed residencies that connect teachers with writers, which consequently support teachers as writers (Eyres, 2016). These are all models of excellence that demonstrate universal, measurable approaches endorsed by specialists.

Moving beyond the days when I was first throwing poems in the sea, if I now take a group of pupils into the woods and ask them to close their eyes and sense the trees, I understand the ‘felt’ experience behind the action and the theories that are attached, the value of this activity to writing and how to negotiate the ideas that evolve.

If I transform a whole classroom into an interactive funfair, I know in advance whether I want to link with fantasy, horror, or realism and I steer the connecting activities based on the outcomes identified. I can assess the direct impact of the lesson on the writing, analyse how well character, setting and genre have been utilised, and give in-depth feedback on ways to develop both the language and the ideas overall.

Throughout this book I have ‘tamed and trained’ my own approaches so they not only have value for others working in education, but also that those same ‘others’ can take them from me and make them their own. All the material has been researched, adapted and piloted at primary and secondary level in order to assess measurable differences and developments.

Teachers can follow the creative writing in the Wordtamer Showtime activities (pages 134–210) ‘by the book’ or they can amend and adapt these to suit their own groups’ needs and abilities. Although primarily pitched at creative practice within the context of literacy, the activities offer multi-modal and cross-curricular approaches.

It is hoped that Wordtamer will be of value to those who hope to learn to teach, those who are learning how to teach and those who are already teaching.

It will also have benefits for anyone who seeks inspiration and the development of crafting skills; those many teachers and professionals I work with who aspire to write stories of their own.

Government reports continually acknowledge the need for more flexible, imaginative practices to be embedded within schools’ literacy programmes. Recognition of the value of extended projects that provoke more depth and detail in writing outcomes resulted in a call for teachers to take more risks and to ‘be inventive’ (Ofsted, 2012). Taking risks and being inventive are the heart and pulse of creative writing, and if new initiatives can continue to support writing at all stages, then models of excellence can literally ‘move English forward’ into the future.

Wordtaming and the funfair of ideas

A significant number of young people get left behind in the writing race, and this follows them beyond primary and secondary learning, dragging like a ball and chain through all their adult lives. There may be many reasons for this, but some studies highlight issues around an overly intense focus on spelling, punctuation and grammar:

only just over half of the pupils (KS3) surveyed saw themselves as good writers who valued the opportunity to use their imagination in their writing. The other half did not think they were good at writing and cited their inability to write neatly, spell or punctuate. These young people had clearly not gained the confidence to use writing for their own purposes and expressed a lack of confidence in terms of technical competence rather than in the messages they might need to convey, and recommendations are in place for initiatives to work with teachers and with pupils to address this.

(Horner, 2010)

This is a complex debate, as it is clear that spelling, punctuation and grammar are essential ingredients for good writing. Theories and practice wrestle with alternating approaches. There is the need to establish these skills in advance of evolving creativity, pitted against a desire for creative, engaging sessions that don’t concern themselves with more secretarial elements. Either way, at both primary and secondary level skills in writing generally lag behind those with reading. Added to this, studies consistently identify gaps in performance between boys and girls. This is not confined to England, or even the UK: ‘Underachievement of boys is a concern broadly paralleled throughout the English-speaking world and beyond’. The gap between girls’ and boys’ achievement in English is greatest in writing (Ofsted, 2009) and this trend continues (see Ofsted, 2012 and DfE, 2016).

A study of under-achieving primary-age boys aligns with the previous Arts Council survey: boys struggled with punctuation, grammar and sometimes even the practical skill of holding a writing implement, but this didn’t mean they didn’t have stories in their heads. Many boys indicated that they wrote at home, when they were free to write material that mattered to them, drawing on their own interests and passions (Warrington and Younger, 2006: 146–9).

I have observed from my own school visits that boys (in particular) can rush at me, tumbling out stories that are lengthy, complex and rich with dramatic ideas, but when I respond enthusiastically with ‘that sounds great, but don’t just say it – write it’, they disconnect. If they write at all, the story becomes a dumbed down version of its former self. Storytelling does have a place in the classroom, and is an art in itself, but it has not evolved into a valid, measurable component within the ongoing teaching of literacy. The development of s...