12

Epistemologically Authentic Scientific Reasoning

Clark A.Chinn

Betina A.Malhotra

Rutgers University

In this chapter, we present a cognitive theory of scientific reasoning, and we discuss implications of this theory for instruction and research. We focus especially on experiments as one important form of scientific reasoning. Our basic premise is that experiments can be represented cognitively as models that incorporate several kinds of inferential connections, including causal, contrastive, inductive, and analogical connections. Reasoning about experiments involves constructing and critiquing these cognitive models of experiments. The theory presented in this chapter is a major extension of an earlier theory, the models-of-data theory developed by Chinn and Brewer (1996; 1999).

Although we focus mainly on experimentation in this chapter, our analysis can easily be extended to other forms of scientific research. Models-of-data theory was originally developed to account for data in historical sciences such as paleontology, geology, or archaeology. This chapter extends models-of-data theory to experimentation. We think that only short steps are needed to extend the theory from these two forms of data to other forms of data such as correlational studies or case studies. In later sections, we will briefly discuss these extensions.

Models-of-data theory provides a basis for examining the nature of reasoning about experiments and other scientific research. In this chapter, we apply models-of-data theory by contrasting the reasoning needed to think about two kinds of experiments: a) experiments typically conducted by scientists, and b) experiments typically conducted by students in schools or by participants in psychological studies of scientific reasoning. We argue that the models underlying actual scientific experiments are fundamentally different from the models underlying most of the simple experimentation tasks currently used in classrooms and psychological studies of scientific reasoning. As a consequence of the differences in cognitive models, reasoning about models of actual experiments involves different cognitive processes than does reasoning about models of these simpler experiments. Indeed, we propose that reasoning about actual experiments is based on a fundamentally different epistemology than reasoning about the simple experiments. Our analysis suggests a need to develop scientific reasoning tasks for use in schools and in psychological studies of scientific reasoning that come closer to reflecting the epistemology of real scientific research.

Throughout this chapter, we will call experiments typically conducted by scientists authentic experiments. Experiments typically found in schools and in psychological studies of scientific reasoning will be called simulated experiments. The reason for using the term simulated experiments is that these experiments are intended to simulate key components of authentic experimentation within tasks that can be completed with relatively limited time and resources. If simulated experiments are successful at simulating crucial features of scientific reasoning, then they can be used to teach students about scientific reasoning and to investigate processes of scientific reasoning.

The outline of the chapter is as follows:

- We begin by briefly reviewing past work on the nature of data.

- We outline models-of-data theory and then present our extension of this theory to experimentation. We also note how the theory can be extended to non-experimental research.

- We turn to an analysis of the dimensions along which authentic experimentation and simulated experimentation may differ. We analyze: a) differences in underlying models, b) differences in cognitive reasoning processes needed to reason about the different models, and c) differences in epistemological assumptions that are implied by the different cognitive reasoning processes.

- We discuss implications of these differences for research, instruction, and assessment. We emphasize the importance of developing simulated tasks that capture the epistemology of authentic experimentation.

What are Data?

Most scientists and philosophers of science would agree that theories explain data. But what are data? Philosophical work on data has been dominated by the issue of whether data are theory laden. The positivists assumed that data are based on direct experiences and are logically independent of the theories that explain them. Later work challenged the assumption that data are independent of theories. Philosophers such as Hanson (1958) and T. Kuhn (1962) argued that data are theory laden, so that the very way in which data are conceptualized is tainted by theories. If data are theory-laden, then data can never provide an unambiguous test of theories, which means that the validity of scientific theories is suspect. Much subsequent work has debated whether data really are as theory laden as Hanson and Kuhn suggested.

The issue of the theory ladenness of data long obscured the question of what data are. Data were most often treated in an unanalyzed fashion. Data were seldom analyzed as having a complex internal structure of their own, and the details of the data collection processes were not given much attention. In the past two decades, scholars have begun to redress the neglect of data. Both sociologists of science (e.g., Knorr-Cetina, 1981; Latour & Woolgar, 1986; Pickering, 1984; Rudwick, 1985) and philosophers of science (Franklin, 1986; Galison, 1987; 1997; Giere, 1988; Hacking, 1983) have developed detailed accounts of the work of scientists, paying careful attention to the actual process of gathering data, including detailed descriptions of how experiments are carried out and interpreted. Psychologists of science have also examined the experimentation of scientists as revealed in their laboratory records (such as Tweney’s analyses of Faraday’s work, this volume) and in their laboratory meetings (Dunbar, 1995). This work has provided a set of rich descriptions of the data-gathering procedures that lie behind what scientists report as “data.” It has made clear that data are complex and that many inferences are needed to link data to theory.

Chinn and Brewer (1996; 1999) have developed a theory of evaluating data that assumes that people represent data cognitively as models. Their models-of-data theory was developed to account for how undergraduates evaluated nonexperimental data such as data supporting or opposing the theory that the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period was caused by a meteor striking the earth. Models-of-data theory endeavors to present a systematic account of how data are connected to theories. In the next section, we outline this theory and then extend the theory to experimentation.

Models-of-Data Theory

Models of Data

Models-of-data theory was originally developed as an account of how individuals evaluate reports of data. The theory assumes that when individuals evaluate data, they begin by constructing a cognitive model of the data (cf. Kieras & Bovair, 1984). Suppose, for example, that a student reads the following report describing hypothetical archaeological data from the American southwest:

One theory that has been advanced to explain why the Anasazi abandoned their cliff dwellings is the theory that the Anasazi were driven away by a drought. Evidence for the drought theory derives from analyses of tree rings. It is well established from the narrow rings found in tree rings that the Colorado Plateau suffered a severe drought between A.D. 1276 and 1299, and this interval corresponds with the time of the abandonment. Recent studies of tree rings from timbers in the ruins on Long House shows that the last construction took place in the late 1270s.

We assume that a reader constructs a model of the ideas in this report using standard comprehension and elaborative processes. The model consists of causal connections and generalizations that connect observed data with the explanatory theory that drought caused the abandonment of the cliff dwellings. Several pieces of the model of data are explicitly stated in the text. Other parts of the data are inferred by readers (cf. Collins, Brown, & Larkin, 1980), who will vary in how elaborate a model they construct (Chinn & Brewer, 1999). Models are thus mental constructions that will vary from reasoner to reasoner.

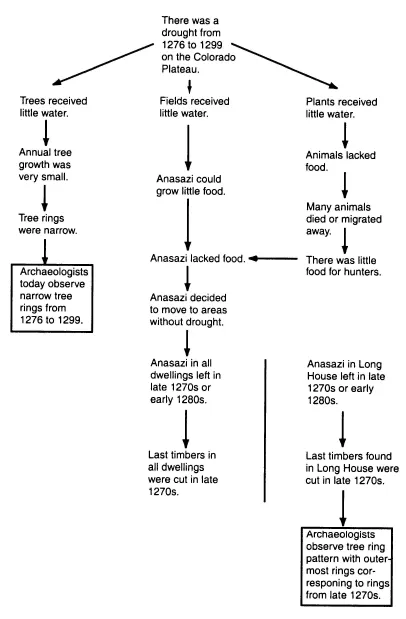

A hypothetical reasoner’s model of the situation described in the text is shown in Figure 1. The model consists of three causal paths intended to explain two pieces of data. One of the two pieces of data is explicitly described in brief report: Archaeologists have observed that trees had narrow tree rings from 1276 to 1299. This first piece of data is explained by assuming that a drought occurred from 1276 to 1299.

The leftmost causal path in Figure 1 connects the hypothesized drought to the tree ring observation: Because of the drought, trees received little water, which caused annual tree growth to be restricted, which in turn caused tree rings for those years to be narrow. Thus, a drought provides a causal explanation for the observed narrow tree rings from 1276 to 1299.

A second piece of data can be easily inferred from the report: Archaeologists have observed that the outermost tree rings in logs in Long House correspond to rings found in the late 1270s. This implies that the last timbers cut by the Anasazi were cut in the late 1270s, and hence that the Anasazi left Long House in the late 1270s or early 1280s. Generalizing from Long House to other cliff dwellings (generalization occurs over the line segment in Figure 1), archaeologists infer that probably all cliff dwellings were abandoned at about this time. The report asserts that the drought caused the abandonment. Although the report does not specify the causal paths by which drought causes the abandonment, two causal paths can easily be hypothesized. One path traces the events by which a drought would cause crop failures; the other elaborates the process by which drought would drive game animals away. These events together would have left the Anasazi without food, a sufficient cause for deciding to move away and abandon the cliff dwellings.

Figure 1. A model of tree ring data supporting the theory that drought caused the Anasazi to abandon their cliff dwellings.

The model of data in Figure 1 integrates the observed data into an explanatory web of connections, consisting of many causal connections and an inductive connection. Figure 1 displays the model of the data in a semantic network as a convenient shorthand for displaying key events and inferences. However, we are not committed to this representational format; mental models are another plausible format (see Chinn & Brewer, 1996).

Evaluating Models of Data

According to models-of-data theory, the reader of a research report constructs a model of data such as the one shown in Figure 1. If the reader’s own theory is consistent with the interpretation embodied in the model, the reader is likely to accept the complete model. If, however, the reader’s theory is inconsistent with the interpretation contained in the model, then the reader is likely to try to discount the model by finding alternative causes for one or more events in the model. For example, with the model in Figure 1, a skeptical reader might accept that the last timbers in Long House were cut in the late 1270s but deny that this was due to the Anasazi leaving. A possible alternative cause is that the Anasazi did not leave but stopped building rooms because their population was no longer growing. Alternatively, a reader might accept both that there was a drought and that the Anasazi left in the late 1270s but argue that the departure was due not to the drought but to other causes such as being attracted to new centers of culture that were growing to the south. If the individual can provide an alternative explanation for any event in the model, the individual can discount part or all of the model. If not, the individual will probably accept the entire model. (For more details, see Chinn & Brewer, 1996; 1999.)

Chinn and Brewer (1999) have presented evidence in support of this theory from undergraduates evaluating data in the domains of dinosaur metabolism and the cause of the Cretaceous mass extinction. Chinn and Brewer noted that the theory had been elaborated only for prehistoric data, as is typical in fields such as paleontology, geology, and archaeology. This chapter will extend the theory to account for other types of data.

Models of Experiments

In this section, we extend models-of-data theory to experimentation, presenting two examples of models of experiments. One purpose of presenting these examples is to provide concrete illustrations that we can use in our later discussions of the differences between authentic experiments and simulated experiments.

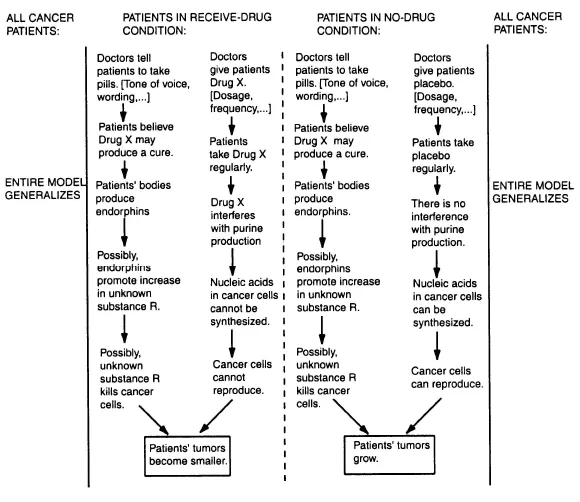

To illustrate how models-of-data theory can be extended to experimentation, consider first a fairly simple example, a clinical trial of a cancer-fighting drug. In this hypothetical two-condition experiment, patients take Drug X in one condition and a placebo in the other. Figure 2 presents a model of the experiment that might be constructed by someone with a moderately detailed understanding of the experiment. A scientist involved in designing or evaluating the experiment would certainly have a much more elaborated model.

The two conditions in the experiment are represented as two separate models, separated by a dotted line that denotes that the two models represent contrastive conditions. In the first condition, represented in the model in the left half of Figure 2, doctors tell patients to take pills that contain Drug X. Those variables that are known to be controlled are listed within brackets at each point of human intervention. For example, the recommended dosage and frequency of taking the drug are known to be controlled, as are the doctors’ tone of voice and the wording used to provide directions to patients. The three dots inside the brackets indicate that there may be other unknown variables that have been or should be controlled.

Figure 2. A model of conditions in a hypothetical clinical trial.

There are two causal paths by which the drug reduces the size of the tumors. The first path reflects the direct biochemical effects of the drug itself, in which the drug interferes with ...