![]()

PART I

Theories of conspiracy theory

![]()

1

From fears of conspiracy to fears of conspiracy theory

The stigmatization of conspiracy theory in academic discourse

In early 1875, a throng of reporters and spectators flowed into Brooklyn City Courthouse to attend the civil trial of Theodore Tilton v. Henry Ward Beecher, the legal culmination of what Walter McDougall has called “the most sensational ‘he said, she said’ melodrama in American history” (551–52).1 A member of the prodigious Beecher clan and leader of the large Plymouth Church congregation, Henry Ward Beecher was already well-known as an outspoken clergyman and social reformer when rumors began to make headlines that Beecher had had an extramarital affair with Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of his former friend and colleague Theodore Tilton. For over two years, the scandal filled the newspapers in Restoration America until Beecher was put on trial. Out of fear of being viewed as one of the “forty thousand preachers to lie it from Sunday to Sunday,” as the women’s rights activist Victoria Woodhull put it (qtd. in McDougall 551), Beecher employed a team of seven notorious and driven lawyers to redeem his good name. His defense strategically portrayed Beecher as the victim of a conspiracy designed by Theodore Tilton and another former colleague of theirs, Henry C. Bowen – a plot, one of Beecher’s lawyers argued in court, which was “the most remarkable conspiracy of modern times” (qtd. in Tilton 808). Two days later, in its detailed summary of the trial’s proceedings, the Boston Daily Journal reported that Beecher’s legal team had called Tilton “a conspirator […] against the character of Henry Ward Beecher” and had “Developed” a “Conspiracy Theory” (“Beecher Trial”; also cf. Figure 1.1).2

FIGURE 1.1 “The Beecher Trial.” Courtesy of Readex, a Division of NewsBank, inc. and the American Antiquarian Society

While it is indeed difficult to ascertain when and how the term “conspiracy theory” first entered the English language, to locate, as Andrew McKenzie-McHarg writes, “a singular moment of creation” (2), it seems safe to assume that during the Beecher-Tilton scandal the term was for the first time introduced to a broader public. Contrary to the Oxford English Dictionary’s explanation, which dates the first usage to 1909, the compound is thus not a product of the 20th century, but of the late 19th century (cf. McKenzie-McHarg 2). This is not surprising given that the legal definition of the term “conspiracy” was also widely debated at this time (cf. Cohen, “Capital” 69–71). In fact, the problem of what qualified as a criminal conspiracy remained largely unsolved until the middle of the 19th century, and many experts complained that “few things [had been] left so doubtful in the criminal law, as the point at which a combination of several persons in a common object becomes illegal” (qtd. in Doyle 3). The first four federal conspiracy statutes passed by Congress during the Civil War and in subsequent years promised to offer more clarity (3–4); going back to the 1863 English Common Law definition, they all, at a very basic level, defined conspiracy as an agreement of two or more individuals engaging in unlawful activities (“Gold Gamblers”).

Beecher’s legal team opted to portray the pastor as the victim of a criminal conspiracy at a time when conspiracy persecutions and allegations had become increasingly popular in U.S. courts and outside. To “develop” a “conspiracy theory” became synonymous with a line of argumentation that presented a hypothesis which could either be validated or refuted. As Andrew McKenzie-McHarg has shown, conspiracy theories also entered the terminology of forensics since journalists, police officers, and detectives investigating crimes showcased “a readiness to build compounds linking a specific kind of crime to the term theory” (4). “Conspiracy theory” was one of many ways to account for the crimes committed – other explanations included “suicide theory,” “murder theory,” or “abduction theory” (4).3 For instance, in 1881 District Attorney Isaac Wayne MacVeagh proposed a “conspiracy theory” to argue against the idea that Charles J. Guiteau had been the lone assassin of President James Garfield;4 the term was also used in two newspaper articles in 1904 which commented on a customs fraud trial (“Theory of Conspiracy”) and the case of a chauffeur’s homicide (“Conspiracy Theory: New Explanation”).

As an explanation in criminal justice and forensics the phrase “conspiracy theory” continued to be used until well into the 20th century. From the beginning, however, these hypotheses prompted heated discussions. During the Tilton-Beecher trial the Daily Critic deemed the defense’s conspiracy theory “improbable” and chided Beecher’s lawyers for “presum[ing] to a surprising extent on the credulity of the American people” (“Beecher Trial”). In a quarrel with the Baltimore Sun in 1894, the Washington Post mocked the other paper for “the fatuous stupidity of [its] cuckoo conspiracy theory” about the enactment of a tariff law (“Great Baltimore”). Most interesting is an article published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in the immediate aftermath of the Garfield assassination. Not only does the article – wrongly – criticize several newspapers for having created the term “conspiracy theory” to explain the assassination, it also expresses disdain for the “revolting” and “horrible” theory itself: “There was infinite wickedness even in suggesting such a thing as possible,” the article deems, “and there is absolute diabolism in discussing it affirmatively.” The newspaper then professes its belief in the common sense of the American people and hopes that while “The vicious few may harbor [the conspiracy theory] and nurse it; […] the vast body of citizens […] will reject it as a horrid libel upon the American character” (“The Conspiracy Theory”; also cf. McKenzie-McHarg 4).

Not only does the article adamantly oppose the idea that Guiteau could have been part of a conspiracy, but it also attacks the conceptual explanation of the conspiracy theory and thereby hints at the semantic shift that the term experienced in the 20th century. It frames the hypothesis as the product of a distorted mindset, puts the term into quotation marks, and calls into question whether the conspiracy hypothesis “can be dignified by the name of theory” (“The Conspiracy Theory”). As several scholars have argued (cf. McKenzie-McHarg 2; Butter, Plots 289), it was in the early Cold War period that the term developed another semantic strand which carried a distinctly pejorative connotation and intellectuals began to question whether the term “theory” was adequate. Since then, the term has come to connote an antiquated worldview, a pathological belief system, or, as one journalist phrased it in the 1970s, “an ideology, a haphazard theoretical system structured around a network of conspiracies” (Donner, “Conspiracies” 657).

The origins of this second semantic strand can be traced to Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies (1952)5 in which he describes and criticizes what he refers to as the “conspiracy theory of society” (High Tide 94; italics in the original). Popper firmly established the term conspiracy theory in academic discourse and helped to conceptualize conspiracy theory as an object of study. In similar fashion, many of the intellectuals who wrote about conspiracy theories in the following decades popularized the term but also contributed to its shift in meaning. In The Age of Reform (1955), Richard Hofstadter intermittently makes use of the term which is, quite tellingly, listed under “conspiratorial manias” (Index iv). A 1956 article on conspiracy theorizing in Harper’s Magazine (Rovere, “Easy”) and the various dissertations which dealt with conspiracy theories in the 1960s (cf. Baum; Remington) are also indicative of the term’s mainstreaming.6 In 1983 the term appeared for the first time in the title of a scholarly publication, in Architects of Fear: Conspiracy Theories and Paranoia in American Politics by George Johnson (cf. McKenzie-McHarg 3).

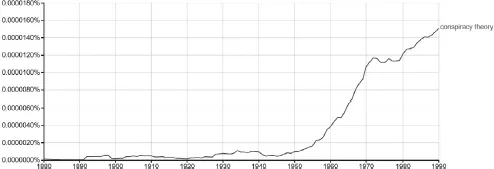

By tracing the origins as well as the popularization of the term conspiracy theory there are two observations to be made: (1) while the term dates back to the second half of the 19th century it only developed into a mainstream vocabulary in the second half of the 20th century, as a quick search of the term with Google’s Ngram Viewer also reveals (see Figure 1.2);7 and (2) the mainstreaming of the term is inextricably linked to theoretical (academic) investigations of conspiracy theorizing. But the scholars, journalists, and intellectuals who began to study conspiracy theories not only defined and described them, they also actively delegitimized the epistemological foundations of the belief in conspiracy theories. In other words, the establishing of the term went hand in hand with its delegitimization; the more popular “conspiracy theories” became, the more they were stigmatized.

FIGURE 1.2 A Google Ngram search of the term conspiracy theory, 1880–1990 (http://books.google.com/ngrams)

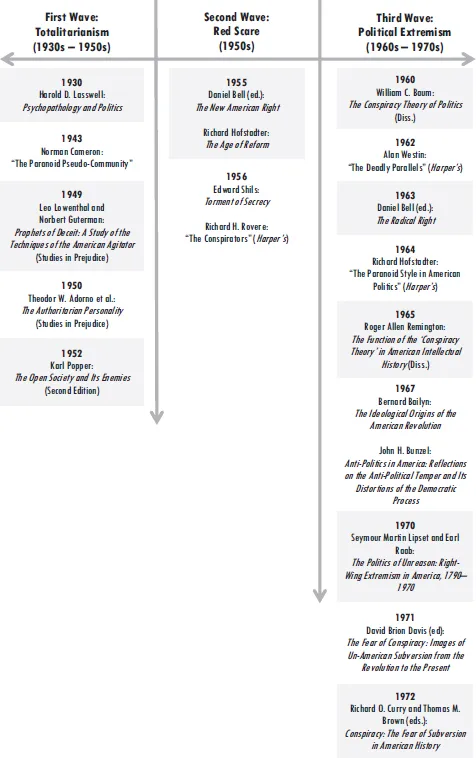

Conspiracy theories existed throughout American history, well before the term itself entered American everyday language (cf. Bailyn; Butter, Plots). While conspiracy theories initially circulated in a culture that accepted them as legitimate sources of knowledge, they later circulated in a culture which marked them as illegitimate. My aim in this chapter, then, is to investigate the semantic shift of the term “conspiracy theory”: to investigate how, why, and when the conceptual model of conspiracy theory was delegitimized. By focusing, above all, on academic writings dealing with conspiracy theory and published from the 1930s to the late 1970s I demonstrate that the conceptual model of conspiracy thinking was stigmatized in academic discourses in three phases (see Figure 1.3). The first phase encompasses the beginnings of conspiracy theory research published between the 1930s and the early 1950s and can be seen as a reaction to the rise in totalitarian regimes in Europe; the second phase follows the height of anti-communism during the Red Scare in the mid-1950s; and the third phase runs from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s when, above all, consensus historians and pluralists denounced conspiracy theorists as the members of a paranoid, extremist fringe of society and politics.

FIGURE 1.3 The three waves: overview of selected writings on conspiracy theory, 1930–1972

While this chapter shows, above all, how an, initially largely intellectual, discourse on conspiracy theory emerged and gained traction, I also want to point at several factors which help to explain why this discourse emerged in the first place. Of course, it is difficult to offer reasons for the stigmatization of conspiracy theory by forging causal connections in an almost conspiracist fashion without sounding either too speculative or too deterministic. Yet, I believe that developments in the production, circulation, and accessibility of scientific knowledge ultimately played into the discursive formation of conspiracy theory. On the one hand, the growing influence of disciplines like sociology and sociology of knowledge with their focus on structural explanations and questions of rationality in the mid-20th century can be traced to transformations in the sciences and the differentiation of disciplines at the turn of the century (cf. Hayek). On the other hand, the trickle-down effect and prevalence of psychological, psychoanalytical, and sociological thought outside of academia in the 1940s to 1960s (cf. Benjamin Jr.), which helped to spread Theodor Adorno’s or Richard Hofstadter’s psychological explanations and definitions of conspiracism, was owed in large part to the popularization of science and academization of audiences in American postwar society.

Newspapers, magazines, and radio broadcasts had begun to dedicate segments to popular discussions of science since the 1920s (cf. LaFollette 8), but the postwar decades witnessed an unprecedented growth in audiences who were receptive to and interested in scientific ideas. This was in no small part thanks to the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act or, as it is more commonly known, the “G.I. Bill,” which was passed by Congress in June 1944 and which provided financial assistance to World War II veterans pursuing a degree in tertiary education. As Beth Luey has shown, 2.8 million veterans immediately benefitted from the G.I. Bill, but, more importantly, college attendance rose by 140 percent during their children’s generation in the 1960s and 1970s (36). While the rise in college enrollment was also due to the overall population growth in the postwar years (36), and the G.I. Bill disproportionately affected college attendance by white men rather than women and African Americans, it “clearly sustained postwar prosperity, fueled a revolution in rising expectations, and accelerated the shift to the postindustrial information age” (Altschuler and Blumin 86).

For the academic sector as well as the publishing industry, the academization of audiences proved to be deeply profitable: college curricula and faculties were broadened and scientific book industries expanded. Again, two infrastructural developments spurred one another, as growing textbook sales between the 1940s and 1970s coincided with the advent of paperbacks in the postwar era (cf. Luey 37). As a consequence, scientific knowledge, including ideas and statements about conspiracy theory, were much more easily available in these decades, from cheap, widely sold paperback textbooks to magazines and newspapers which “translated” scientific ideas into a more popular form, and were widely consumed by audiences who were better equipped than ever to engage with theoretical assumptions about human psychology, sociology, or political science – and the fallacies and intricacies of conspiracist beliefs. The fact that Hofstadter, at the time a noted, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, published “The Paranoid Style” in Harper’s, a magazine that catered both to intellectual and popular demands, singularly underlines the changing media landscapes of academic publishing and the broad impact that his, and others’, dismissal of conspiracy theory as paranoia could develop at the time.

Finally, it is important to point at the intellectual habitus shared by most of the academics who devoted some of their research to conspiracy theorizing in the 1940s to 1970s. The common theoretical and ideological foundations of the academic writings on conspiracy theory in these years “were not so much convergences of individual beliefs,” Alexander Dunst explains, “[but] consequences of a shared cultural formation”: “with national socialism and the Holocaust [and anti-communism] an immediate presence, Western intellectuals felt called upon to defend a modernity seemingly under threat” (Madness 32). This is not to suggest that these scholars joined a conspiratorial union to eradicate any conspiracist thoughts, but to emphasize that the early scholarly literature on conspiracy theory has to be seen as a series of reactions to certain historical, political, and socio-cultural events and transformations perceived as attacks on intellectualism, the autonomy of the sciences, and democratic principles. The theoretical concepts which these intellectuals offered, such as Hofstadter’s phrase of the “paranoid style” or the nexus between conspiracy thinking and political extremism, thus also represent historical concepts and, while many of these early ideas on conspiracy theorizing still remain insightful, should be handled with care by 21st-century scholars of conspiracy theories. These concepts and the term “conspiracy theory” itself stem from particular moments in American history when Americans were still concerned about conspiracies but also, growingly, showed concern about conspiracy theories.

The beginnings of conspiracy theory research

When in 1922 journalist Walter Lippmann published Public Opinion, a pessimistic critique of modern democracy, he was inadvertently one of the first in...