There have been many books written about sleep, the varying theories about its nature and purpose, informed from multiple angles (adults, infants, animals, and even plants!) over many decades. As stated in the introduction, the purpose of this book is to deliver information that is current and state-of-the-art: to people with insomnia to help improve their sleep experience; and to healthcare practitioners in order to inform and enhance their practice. As a result, this chapter will not engage in a lengthy repetition of the evolving theories as to the purpose of sleep over the years, but will describe where we are at the moment and how this can be of use to the individual with a sleep problem and the practicing healthcare professional, restricting its range to human sleep in health and “disease”. This chapter is subdivided into sections that will examine our current knowledge about sleep from different perspectives. After an initial examination of the various states of consciousness, we will look at circadian rhythms, sleep stages, current ideas about memory, how sleep changes as we age, the influence of light on our sleep, tiredness, how social cues impact on our sleep, and then how physical and psychological insults can reduce the quality and quantity of our sleep. This chapter will then conclude by pulling all these elements together to explain the complex and dynamic nature of sleep. After reading through this chapter it is anticipated that the reader will have a good base-knowledge about the science underpinning what it is to sleep in health and in poor health, so providing them with a good foundation on which to introduce therapeutic interventions to help improve sleep in themselves, and for their families, friends, and clients.

States of consciousness

So to begin with it is worth looking at our minds and how we live life as perceived by our brains. Essentially there are three states of consciousness, which are all very different from one another; and our brains shift between these states continuously throughout our lives, every day, all the time. If we do not allow this shifting to occur, we suffer. If anyone has stayed awake for more than a couple of days and nights, then they will be acutely aware of what this feels like. Jet lag, shift work, being a new parent, there are many ways to experience these feelings, in fact everyone knows the feeling, we call it “tired”, we call it “fatigued”. This is because we need to shift our consciousness regularly, as to exactly why we need to do this still remains something of an enigma, although we are becoming increasingly aware these days that it has something very important to do with memory (to be discussed later in this chapter). The consequences of not shifting are serious, from mild discomfort, to billions of lost working hours (and so money), and huge industrial accidents with major consequences to people, economies, and the environment. The big things we have all seen on the news—Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, the Exxon-Valdes oil tanker spillage, the Three Mile Island nuclear core melt down, the Challenger space shuttle explosion, and so on. The smaller, subtler impact of mild to moderate tiredness and fatigue on the population is much more difficult to measure, but estimates are massive. In the US, where there have been detailed investigations conducted into the cost insomnia to society indicate direct cost estimates of fourteen billion dollars annually, rising to $100 billion for indirect costs (including work-related accidents and lost productivity), these were estimates from early in this second millennium (Sivertsen & Nordhus, 2007).

So what are these three states? First—we are awake, our brains are mildly to hugely active and we are “conscious”, we have volition, we are in control. Our attention is malleable and we range from “alpha” type activity (for example: zoning out in front of the television; or driving home from work and not really remembering the journey). Alpha states are where our brains could quite easily slip into another state of consciousness, the opposite end of the wakefulness spectrum is occupied by gamma wave activity. Gamma is where we are super-alert, and the best way to get our brains into this state is to play a team game like football where we are paying attention to ourselves, our team, the opposition, the ball, the opposition’s goal, our goal, who to pass to, where to run etc., playing 3D “Shoot-em-up” maze games on computer consoles has a similar effect. State one is conscious, awake, aware, and in control; but every twenty-four hours we need to spend a significant proportion of time (between a quarter and a third of the time for most adults) in the two other states which occur during sleep. Namely REM and non-REM sleep.

Sleep, in many ways, is the opposite of being awake. We are not aware, we cannot shift our attention (with the exception of a few people who experience “lucid” dreams, but even then that ability to shift attention is quite limited), and we are “unconscious”. Different parts of our brains go quiet or acquiesce, while other parts become more active, and we are beginning to get an understanding as to why, particularly with advances in functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) techniques. More on this later. REM sleep, as most people are probably aware, stands for Rapid Eye Movement sleep and our sleep period shifts between REM and non-REM sleep in a ninety-minute cycle (in the adult human), we will talk more about this “circadian” rhythm of the REM—non-REM cycle in the next section. Again, why we cycle between these other two states of consciousness whilst asleep is still something of a mystery, but we will look at some possible explanations for this later on.

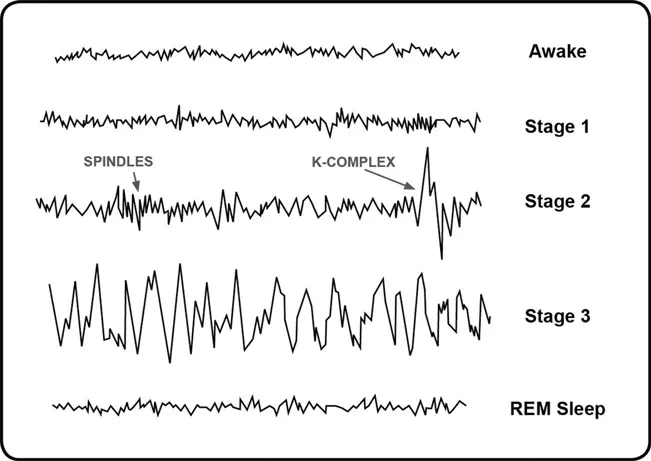

If we take a look at Figure 1 (below) we can see a graphical representation of the electrical activity of our brains in these three states of consciousness. “Awake” is characterised by high frequency, but low amplitude (or height of the wave) waveforms—the higher the frequency, the more “awake” we are, so gamma activity is very fast, beta waves are intermediate and alpha relatively slow waveforms; and that makes sense if we think about how active our waking brains are when we are engaged in different activities. As our brains tire and get ready for sleep we lose the higher frequencies and become more alpha dominated. We know what this “drifting off” feels like, because we do it every night and have done so, every night, for the whole of our lives. It is very difficult to go to sleep if we are very excited (i.e., our brains are banging away at a high frequency). So gradually our brainwaves slow down, we “phase-out”, we “drift-off” and this (electrically speaking) is our brainwaves slowing and the amplitude (height) of the brainwaves increasing. We have entered stage one non-REM sleep—also referred to as transitional sleep. This stage is not regarded as true sleep, but an interface period between wakefulness and sleep. This stage is characterised by alpha waves and some theta wave activity, but a loss of the higher gamma and beta frequencies. We spend a very little time in this stage, but some interesting things can occur to us during this time. We can twitch and jerk ourselves back to wakefulness here (so-called hypnic jerks); our arms and legs can feel heavy, twitch, and feel uncomfortable (restless legs syndrome (RLS), and periodic limb movements (PLM)) can also occur here; and we can have, sometimes vivid, visual experiences: hypnogogic (going to sleep) and hypnopompic (leaving sleep) hallucinations. Usually though, we pass through this stage relatively quickly and without incident into stage two non-REM sleep, the lightest stage of true sleep. This stage is again characterised by a reduction in the frequency and an increase in the amplitude of the brain’s electrical waveforms, but is identified by the appearance of K-Complexes and Spindles (see Figure 1 below), and by a loss of alpha and a predominance of theta wave activity. These K complexes and spindles are enigmatic in their own right with uncertainty about their true function, but they are probably resultant from brainstem control mechanisms that may serve as an external noise suppression feature to allow us to maintain sleep and progress into our deeper “restorative” sleep. These deeper stages three and four of non-REM sleep are collectively known as deep sleep, delta wave sleep, or slow wave sleep (SWS) the latter being the most popular (Rechtschaffen & Kales, 1968). Recently stages three and four have been grouped together and we now refer to stage three only as SWS.

Slow wave sleep is again characterised by a reduction in the frequency and an increase in the amplitude of the brain’s electrical wave activity. If one compares these waves to those characteristic of wakefulness in Figure 1 below there is a striking difference. These big, deep, and slow waves are the waves that we need to get every twenty-four hours to restore, refresh, and enable us to live functional lives. Without them we suffer the consequences, this kind of sleep is fundamental and we have got some pretty good evidence as to why. We will look into these after a quick word or two about REM sleep. So sleep stages one to three collectively comprise state of consciousness two—non-REM sleep.

State of consciousness three is REM sleep. REM looks like wakefulness (please see Figure 1 again), which is why it has sometimes been referred to as “paradoxical” sleep. If one just looks at the electrical activity of the brain (by sticking electrodes on top of the head and measuring the minute electrical activity of the brain’s cortices through the scalp, (this form of assessment is referred to as the electroencephalogram or EEG) we see what looks like state one—wakefulness. However, if we place other electrodes (under the eyes and under the chin, the electro-occulogram and electromyogram respectively) we see rapid eye movements, hence REM, and a loss of muscle tone in the muscle under the chin. The placing of electrodes in an EEG, occulogram, and myogram combination is referred to as polysomnography and is the way sleep is measured in a sleep laboratory. There are sometimes other electrodes placed on limbs, respiratory and cardiac areas to measure other physiological responses too. The reason for the myogram electrode is to detect atonia, or paralysis. A key feature of healthy REM sleep is a loss of muscle tone. If you have ever woken up with a damp pillow, this is because you have been in REM, sleeping on your side and you have dribbled out of the side of your mouth as your jaw has slackened during REM periods. We are still not sure why this paralysis in REM occurs, but there are numerous theories, including: not acting out our dreams, reducing activity so we do not awaken and remain asleep etc. Indeed, the whole purpose and reason for REM remains largely debated with multiple theories abound as to the phenomenon. There are memory-related hypotheses, the central nervous system stimulation (ontogenetic hypothesis), scanning and sentinel (observing the environment for threat) hypotheses, and even a defensive immobilisation hypothesis, whereby we look as if we are dead and so are left alone by potential predators. It may well be that there is truth in a number, or even a combination, of these theories and we will return to one of the memory hypotheses later as this seems to have the most credibility and application in modern humans.

So there are the three states of consciousness, Awake, REM sleep and non-REM sleep. We will return to these ideas in further sections of this chapter to fill out on the current thinking as to purposes of the sleep states, and their significance to the primary state of wakefulness, which affects us all. Before this though, we will take a brief look at the circadian rhythm.

Figure 1. Electrical waveforms of the three states of consciousness.

Circadian rhythms

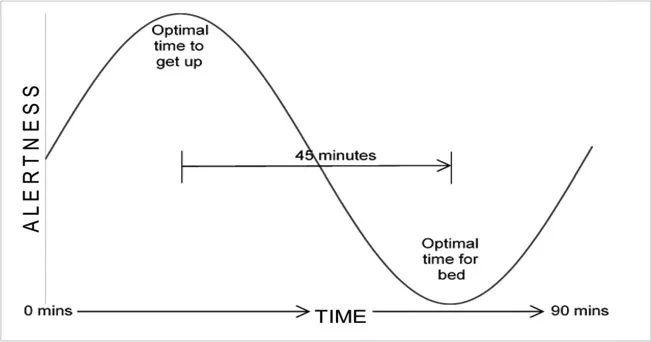

There is a clock inside our brains, which operates continuously and without our conscious awareness, controlling a whole range of our physiological functions. This clock is not exclusive to humans, all animals and even plants have “rhythmicity”, periods of activity interspersed with regular periods of inactivity or quiescence. This rhythmicity was first noted as far back as 4BCE, but the first experimental evidence of their existence was conducted on plants in 1729 by a French scientist called Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan. Since then several periodicity genes have been identified, including: the CLOCK, PER1, PER2 and PER3 genes, simpler organisms have just one of these genes, more complex organisms have two, three, or all four of these genes, whose effect is to provide the host organism with this internal, or endogenous, clock. Humans have all three of the PER genes and the CLOCK gene and these are known to effect the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) two distinctive groups of cells at the back of the hypothalamus in the centre of our brains. Adults have a circadian rhythm of ninety minutes, and this is very regular. Even in people in the advanced stages of dementia, this endogenous rhythm clicks along continuously and many of our functions are controlled and influenced by it. The cycling of REM and non-REM sleep follow this rhythm. Hunger and thirst, urine production, alertness, even creativity follow this rhythm, along with many other functions. Here are a couple of practical examples that help to explain the phenomenon: We are all familiar with a dip in alertness mid-afternoon, and another before we go to bed, at these times our circadian rhythm is reaching a minimum, our alertness is at its lowest, and it is here when we can easily initiate sleep. If we wait half an hour though, our alertness is on the rise and we begin to reach a peak, this is when sleep is very difficult to initiate. If you have ever shifted your bedtime from its normal time, then it is often difficult to get sleep. For example: “I’ll be getting up early tomorrow to catch an early flight, so I’d better go to bed early,” and then you cannot get off to sleep until the usual time. Or, you go to bed later than usual and think: “Why can’t I sleep, it’s past my usual bedtime, I should be tired and so I should be able to get to sleep”. If you want to shift your bedtime from its usual slot then you need to move it by ninety minutes to catch the preceding, or succeeding, circadian dip. This can be hugely effective in the therapeutic intervention for insomnia and we will return to this later in Chapters Five and Six on the treatment of sleeping problems.

* * *

Another example of the circadian rhythm in action is something many people will be familiar with: the “Eureka moment”. If you have ever found yourself “blocked”, for example, you cannot think of an answer in an exam; or you cannot seem to find the right words to express yourself when writing something; or you are not performing to your usual standard in a certain task etc., then you are probably “dipping out” in your circadian rhythm. Leaving the task and returning to it forty-five minutes later and, suddenly, the answer is there, the words flow, the block has gone, the Eureka moment arrives—as your circadian rhythm is peaking. This is easy to see in action if you ever watch professional tennis matches, or snooker on the television. These matches are long in duration and so it is possible to observe individual players performing well, and then later they seem to go “off the boil”. These fluctuations in performance are driven by the circadian rhythm. There is a large, unexplored opportunity to use the circadian rhythm to offset poor performance and optimise periods of high performance, not only in the sports arena, but in all of our lives, both socially and professionally. Knowing your own rhythm and scheduling tasks and activities around it can enhance your performance and, perhaps more importantly, avoid tiredness-related errors and accidents.

Figure 2. One cycle of the adult human circadian rhythm.

Figure 2 above shows a simple illustration of one cycle of the circadian rhythm.

As mentioned above the circadian rhythm in adult humans has a period of ninety minutes, however, this is reduced in children and infants (Czeisler, Zimmerman, Ronda, Moore-Ede, & Weitzman, 1980). The very young have circadian rhythms of around forty-five–fifty minutes from birth and into the first year of life. The circadian rhythm then extends out in toddlers and young children to around sixty minutes, before extending out again to the ninety minute, adult period of ninety minutes around mid-childhood (Bes, Schulz, Navelet, & Salzarulo, 1991). The field of chronobiology is huge, but, for our purposes in this book, we will only refer to the circadian rhythm in its relationship to sleep. The following section examines the various sleep stages, the passage of which is determined by the circadian rhythm.