- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is an account of the psychology of romantic love in the context of a theory of emotions. The account develops out of studies in brain psychology and the extension to topics in process-philosophy, such as the nature of value and belief, and the central role of feeling in mental process. The approach is subjectivist, that is, from the internal standpoint, and in this respect it differs greatly from the externalist and objectivist trends in modern cognitive science and empiricist philosophy. Love is the ultimate in value, so that a theory of love is also a theory of the nature of value and its relation to feeling, belief, and to drive and desire. The role of intention, reason, and appraisal is critiqued. The relation to other feelings, such as jealousy, envy, anger, loss and grief is discussed in terms of a general theory of emotion and the basis in a process account of the mind/brain state.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Love and Other Emotions by Jason W. Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Falling in love

A man who is “of sound mind” is one who keeps the inner madman under lock and key.

—Paul Valéry, Mauvaises pensées et autres (1943)

Introduction

We have all fallen in love or wanted to fall in love, and for those who have truly loved, when they look back, they often feel that falling in love was often the most wonderful part of being in love. There are so many reasons why people love each other, not only romantic love but also the love for family, children, pets, and possessions. One can fall in love quickly, at first sight as we say in English, in a coup de foudre (struck by lightning) in French, or love can grow slowly like a friendship that becomes romantic. The sexual can be a powerful bond or it can pull a couple apart. There are loves and longings that are stronger for being unconsummated. A couple can meet at a bar, a blind date, or on the internet. There is the wanting to fall in love, the fear of love or dependency, thoughts of past loves, inhibitions, biases, predispositions, loneliness, commitments to others, treasured memories, and painful disappointments.

There is the readiness, the timing and openness for a new love, issues of gender, age and social or educational inequality. There is the relation to hate, despair, rejection, humiliation and sacrifice, and to feelings of agency and helplessness. Given the complexity of the context behind every act of love, and the multitude of needs and predispositions, one can say that there are no wrong reasons for falling in love, just the wrong people to fall in love with. The topic is so difficult that it is unlikely any two people will agree on a given interpretation. Still, mindful of the warning above, I would like to offer some thoughts on this age-old subject from the standpoint of process (microgenetic) theory.

Psychology of love

Love is a form of value, and value takes many forms. It begins with drive in the unconscious (Ucs) core of the self. Core value is bound up with drive in relation to the self-preservative instincts, such as hunger. For microgenetic theory, the core category and the drive do not come together but are fused from the beginning in a single construct. Specifically, every affect has a conceptual frame and every concept has an affective tonality. The broader implications of this view are that feeling is the process of becoming and concepts (objects) are the substance of being (Brown, 2005).

The initial drive-representation is hunger, which is primary and unitary, replicating the self. Sexuality develops later as a secondary drive, replicating the species. First, the organism is replicated, then the population. Aggressive and defensive attitudes are vectors of drive expression. They take the drives outward in approach and avoidance, fight and flight, domination and submission. The category of the drive-representation develops to a concept and its affective tone, what I call conceptual-feeling, that aims to an object. The global pre-object (category) of drive narrows to the object (concept) of desire (fear, etc.), that is, the drive-category specifies an object-concept. Core self- and drive-category, say the unconscious self and the drive of hunger, partition to the conscious (Cs) self, concepts, images, and intentional feelings. Concept and feeling, though bound together, are now directed to objects that fulfill or satisfy feelings such as wishes, desires, or fears. A desire can be for an object in immediate perception or one thought about. It can be in the present, past, or future. The ability to think about an absent object is probably uniquely human. It is essential to loving, which develops so much in the imagination.

Instinctual feeling begins with a drive-category in the unconscious self and fractionates to conceptual feeling in the conscious self, where the object-concept is bound up with intentional feeling such as hope, fear, or wish (see Figure 2.1). The object-concept and its affective tone—the idea or memory of the person and the feeling for the person that expand in the imagination as part of the developing object—continue outward to become valued objects (others) in the world. This may be a difficult part of the theory to understand but to the extent such data are relevant to the theory, it is consistent with work on brain imaging. For example, the caudate nucleus is active in individuals who have just fallen in love. In those who have been in love a longer time, anterior cingulate and insula are activated (Fisher, 2004). The caudate and linked structures are associated with drive states, the latter regions are part of the wider limbic formation associated with subtler affects and experiential memory.

The debate in psychology whether love is volition or need, that is, intentional or involuntary, or what role decision plays in falling in love, reflects the proximity of the dominant segment to drive or to desire. The closer to drive, the more love is like unconscious need. The closer love is to desire, the more it is like wish, want, and intentional feeling. Volition does not precede and motivate action or emotion but is part of the same phase to which emotion develops. More precisely, the phase of desire is also one of volition, choice, and intentionality. One does not cause but accompanies the other. There is no sharp distinction since the dominance of one phase over another fluctuates. One moment an individual is madly in love, the next, there is indecision or uncertainty. This reflects the momentary accentuation of one or another phase in the actualization sequence. Love can begin with need and evolve to desire or it can begin with desire and descend to need, and find its complement in the needs of the beloved.

The conceptual-feeling—the feeling inside the developing object or object-concept of the beloved—externalizes with the beloved yet remains part of the pre-figuring concept. The feeling of desire that is part of the beloved in the object-development externalizes in the lover’s mind as it moves outward into (as) the external world. We think the objects we see are the real physical entities that exist as we see them. Actually, the world is the outer rim of the mind filled with perceptual images that appear outside and independent of the mind in which they develop. This does not imply the absence of a physical world, for unless a person is mentally ill or dreaming, the model is so accurate it might as well be the real-world.

We are usually unaware of the small quota of affect that inhabits all objects in the perceptual field. The trickle of feeling in the external field traces back to the drive-category. The perceptual field divides into innumerable objects like the tributaries of a great river, while the feeling that accompanies them narrows down to a partial affect. This feeling is the seed of object value. We know this occurs because in cases such as schizophrenia with depersonalization or derealization, feeling is withdrawn and objects seem unreal or mechanical. The change affects all objects, trees, dogs, people, who now appear as props, automata, or mannequins. The object also withdraws. It no longer exists as real and independent. The feeling that normally goes out with the object is felt within the mind from which it developed. When this occurs, the object becomes more thought-like and less independent. If the withdrawal is more extreme, or the world and its feeling-tone do not fully exteriorize, as in psychosis, the person may not know if he is awake or dreaming.

A similar process occurs in love, as the loved object withdraws to antecedent phases in the imagination where the real growth of love occurs. It is not without reason that one says, I am crazy about you, or I am madly in love with you, or to say one’s “head is in the clouds”—in French, “septieme ciel”—for lovers are presumed irrational. To say one is “head over heels” in love does not mean postural disequilibrium but mental instability. By irrational is implied that love is not the result of a reasoned analysis or decision, not concerned with truth but reinforced by post hoc justifications. More importantly, true, passionate, or romantic love depends on layers in mind that are unconscious, pre-logical, and bound up with animistic and metaphoric thought (see below).

Interest

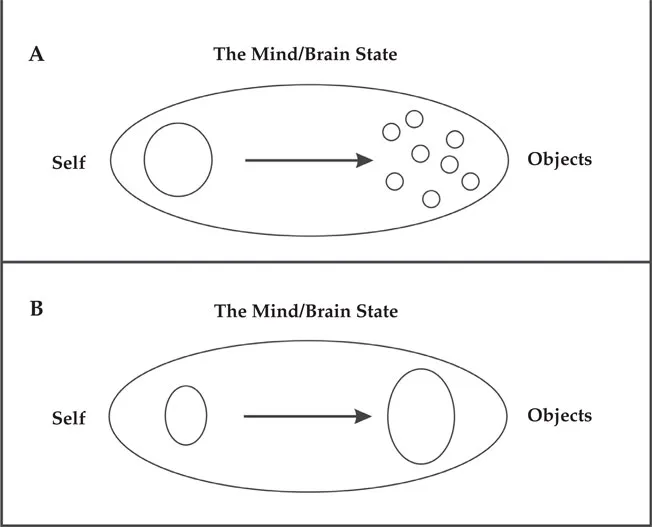

The initial sign of feeling in the world is the existence and reality of objects. We know this because it is altered in psychotic cases, when feeling is withdrawn and objects seem unreal. An affective tonality accompanies the object as it develops outward to the world. Ordinarily, this trickle of affect is evenly distributed over the field. Interest occurs when feeling is re-allocated from a uniform distribution in the field to one object or event (Figure 1.1).

Let us ask, what happens when you first see the person you will fall in love with? In the beginning, he or she is just another person in the world. Interest is the first sign of value, or value transmitted outward into the object as worth. It is located between desire in the mind and the trickle of feeling in the object, straddling inner and outer as an accentuation of the feeling that passes outward with the object. Interest can be weak or strong, and felt as personal or impersonal. We feel interest for someone or something, but we may also say that someone or something has interest for us. We say I am interested in that person or that person interests me, as if we are uncertain whether interest comes from the self or the other. Interest may start as a slight preference. Interest is perceived as value for an object (other) or the value the object has for itself. We say beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and we say love is in the heart, but it is the act of loving or beholding that transfers those qualities to what is perceived. According to an emphasis on the inner or outer pole in the trajectory of desire from the core self to external objects, value may be felt in the self as need, want or evaluation, or it can be assigned to the object, as worth or intrinsic value.

Figure 1.1. Feeling accompanies the object-development outward to perception. All objects have an affective tonality that is ordinarily evenly distributed over the field (A). With interest, affect becomes concentrated in one object or event as other objects fade into the background (B). This focal attention, or interest, is the initial stage of love.

The composer Janáček asked, why do I pick this daisy in a field of daisies? Why did I notice this person in a room filled with other people? Often we cannot say what attracted our attention. The preference is derived from earlier unconscious segments, of which value in the other is a surface manifestation. The feeling that is normally distributed over the entire field is now enhanced in one object. Interest occurs when the feeling hidden inside all the objects of the field is sequestered in just one. It is a mode of attention to one object at the expense of others. We are speaking of love, but an object of interest can be anything, a flower, a rock, an idea, or a sunset.

With interest, a phase preceding objectification is activated so as to dominate the perception. Other people and events recede into the background. Put differently, feeling (and its object) undergo a retreat from externality—though the world remains external—and the phase of inner feeling is accentuated. At this point, the value of the other is not pronounced. Attention may be distracted or shift to someone else. You may never see the person again. But suppose there is an exchange of glances or smiles, and the interest is mutual. You talk to each other and discover after minutes, days, weeks, or months that interest has grown to curiosity, even affection. The person takes on greater value; his or her attributes are now special, unique, and admirable. You think about the other and want to be together. At some point, if feeling grows, you realize you are in love. This can happen even if you are not loved in return or with the same intensity, though usually the one who loves imagines or hopes to be loved, or thinks it is only a matter of time before the love of the other is received, or believes the more love that is given, the more love will be returned.

This scenario is familiar to all who have loved, or believed they were in love. The reason that falling in love for many is so intoxicating is that the value flowing into the beloved is, in reality, surging in the self. For interest or valuation, the dominant segment in the actualization of the other recedes from full objectification to an idea or ideal. The other is no longer another object in the world but a concept in the imagination. At this phase, feeling is magnified. As interest becomes more intense, other feelings are evoked, curiosity, intrigue, anxiety. The feeling that went out to the world calls up earlier segments in the actualization process, precursors associated with wish, hope, or desire. The object of interest no longer need be present. Feeling is linked to the concept, not the actual person, allowing it to fade or grow stronger in the imagination. The transition from interest or focal attention to affection and love recaptures segments—markers—of phases in the original perception as the dominant segment descends (is revived) to the Cs self.

Gradually, the other becomes the beloved. The fulfillment of desire creates a sense that the beloved complements an imagined emptiness before the beloved appeared. The union with the beloved gives the feeling of wholeness or completeness not present before. It is the basis of the oneness or the soul-mate that lovers are seeking. The intensity of feeling that goes into the beloved increases his or her worth, which in turn validates the love that is given and is often sufficient to overcome deficiencies—or idealize them—and offset setbacks, arguments, and rejection. The fights and reproaches establish the limits and test the bonds between lovers. After an argument, she wonders, will he call? He asks, will she return? A love that survives builds up trust, but over time disputes can lead to resentment.

The activation of feeling and the inward retreat have parallels in other spheres of object-concepts. In meditation, the focus begins with a single object or activity at the expense of others. All objects save one are unattended, and as that one grows, others recede. Eventually, attention is suspended from all objects except one. There is withdrawal to antecedent object-concepts, then deeper categories, finally it is claimed, to the ultimate ground of existence. Mystical regression is like love in that it leaves behind the world of objects in a descent to non-self, oneness, and total immersion. There is an absolute focus and faith in the object of feeling. The mystic will endure deprivations and mortifications to achieve god-union. The lover will go through rings of fire for his beloved. We do not without cause say all is fair in love and war. In Christian mysticism, Christ is the lover and the end of descent is union with god in love. Love for another person is like this in that the goal is selfless union with the beloved. David Bradford has written, with good reason, that love is mysticism for the ordinary man.

The flow of feeling and objects into (as) the world makes everything that is seen, touched or heard seem vibrant and alive. Feeling arising in the observer is felt in the object and in the observer. In primitive mentality, the awareness of mind in objects is the basis of animism, in which all nature—animals, trees, the wind, the tide—is penetrated by mind or spirit. The separation of internal and external is indistinct. Objects take on totemic or magical powers. The layer of animistic thought close to dream, just beneath the surface of rationality, comes to the fore in love when we say we have fallen under a spell or think of love as a kind of magic, an enchantment, as in fairy tales of witches brews and magical potions that make one fall in love.

If the beloved, and the feeling for the beloved and, I would add, the feeling perceived in the beloved, all flow out of the lover’s mind, this transfer or ingress of feeling must be the basis for perceiving others as having feelings of their own. This concept is difficult to grasp. We see people and assume the feelings we recognize belong to them, not us. We have certain feelings about a person, but we do not believe the person’s feelings come from us. We do not think we are the cause of that person’s anger, pride, envy or depression. It seems strange to say that feelings in others are derived from our selves. But causing feeling in the other, and feeling the other’s feeling, are different events. Everything happens in the observer’s mind, including the feelings perceived in others, which trace back to the observer. This does not mean we create those feelings, no more than we create the person who feels them, even if the other is an image created in the observer’s mind. Others and their feelings are self-realizations, models of what we think they are truly like. Because we see a model, not the real thing, we can easily be mistaken when our own thoughts and feelings are read into someone we love. This explains why we are often misled in thinking we are loved as much as we love. We see a smile or feel a hand on our arm, have warm conversation or exchange sex, and imagine those gestures are signs of the love we are seeking. For a long time we may deny we are deceived or unloved. If we acknowledge this fact for someone we love deeply, we feel foolish and betrayed. Unrequited love invalidates the love we feel and vitiates the worth we extend to others or attribute to what is truly in their hearts.

The “chemistry” of love

We often speak of the “chemistry” of love, not as a chemical reaction but as a sign that we do not really know what accounts for who we fall in love with. We can describe the qualities of the other and say this is the basis for our love, but the reasons are deeper and impossible to know. After all, to say the lover fulfills something the self needs or lacks, or that the person we love completes the self, assumes that people know themselves so well they can say what is lacking in their self-concept. Most people have no idea what their core self is like. It is unconscious, and thus unknowable. We are informed of who we are by the consciousness of our acts and thoughts, the patterns in our behavior, and the reactions of others. We know ourselves as little as we know the reasons why we have fallen in love with a particular individual. This is why we so often make mistakes when we fall in love. The choice of a partner can say more about who we are than all the analyses, self-justifications, and rationalizations that come with it.

This points to the fact that the idealization of attributes is not sufficient to account for love, for too often love is as much for imperfections, weaknesses, or vulnerabilities as for positive attributes. Here we see the influence of Ucs need over conscious desire. The inability to know the Ucs core and the shifting Cs self leads many to search for the true, genuine, or authentic self that is assumed to underlie its surface manifestations. The problem for the one who loves is that even greater knowledge of the true self, if there is such a “thing” as the true self—which is knowledge that comes to some naturally with aging and an acceptance by way of the reactions of others, or from successes and failures in life, that is, a pragmatism as to personal strengths and weaknesses—does not prevent the incomplete self from loving someone who fulfills or completes them in one way but mistreats or disappoints them in another, for others have needs of their own that may not be satisfied by the one who loves them.

This core Ucs self has the beliefs and values that make up character and the attitudes and behaviors of an individual personality. These determine who, how and what we will love. In passion, if not in platonic love, the choice may reflect a failure to accept shortcomings, or an excess of pride and contentment. A person who chooses someone to complement or fulfill what he or she is lacking achieves a degree of complet...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER ONE Falling in love

- CHAPTER TWO Theory of the emotions

- CHAPTER THREE Love and desire

- CHAPTER FOUR The reconciliation of the emotions: love, envy, and hate

- CHAPTER FIVE Desire for things

- CHAPTER SIX Love and pathology: a note on psychoanalytic theory

- CHAPTER SEVEN Pornography and perversion

- CHAPTER EIGHT Kindness and compassion

- CHAPTER NINE Belief and value

- CHAPTER TEN Philosophy of romantic love

- REFERENCES