![]()

PART I

The triple helix concept

![]()

1

A UNIVERSAL TRIPLE HELIX

Silicon Valley’s secret

The ultimate source of the Valley may be found in a triple helix dynamic, shared with the Boston region. Other regions have had dyadic university–industry or university–government relationships regularly present, or even sporadic triadic ones but these two regions are unique in having had interaction among university, industry and government as relatively equal partners and been “innovative regions” for more than a century.

Fostering university–industry–government interactions is the secret of innovative regions such as Silicon Valley and Boston but significant ideological, cultural and resource barriers impede their development. In these two regions, driven by necessity and vision, academic leaders such as President Karl Compton of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Provost Frederick Terman of Stanford and their colleagues put aside ideological blinders and invented a new innovation model of knowledge-based economic and social development. Visiting world leaders, from France’s de Gaulle to Russia’s Medvedev, have toured the Valley, seeking a clue to its success even as scholars try to tease out a unique explanatory feature, such as firm organizational style (Saxenian, 1994; Caspar, 2007). Deep triple helix roles and relationships may be found behind the libertarian ideology of contemporary Silicon Valley hidden by a mythos of heroic individual entrepreneurs, exemplified by Steve Jobs. His tale, memorialized in an opera The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, is an updated version of the 19th-century Horatio Alger “rags to riches” story that legitimated a previous generation of private enterprise with relatively obscure public roots (Ng, 2015).

A long-term pattern of apparently disconnected dots constitutes a triple helix that underpins the emergence of iconic firms like Apple and Google and a plethora of more recent start-ups that characterize Silicon Valley’s surface. In Northern California, US Navy support for advanced radio R&D in industry in the early 20th century was followed by firms’ interactions with Stanford University, raising the level of the university’s technical base from which start-ups began to emerge (Lécuyer, 2005). The location of a government aerodynamic research center in Sunnyvale helped create a similar parallel dynamic that persists to this day. Post-war government-funded R&D attracted by Stanford expanded a start-up dynamic, surrealistically satirized in an HBO television series based upon a Silicon Valley engineer’s 1980s experiences (Leslie, 1993; Lowen, 1997; Silicon Valley, 2014). A CIA venture capital arm is an investor in Palantir, a leader in deep data mining, while the Google founders who met at a Stanford computer science department orientation for new PhD students were part of a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)-funded research program on search that supported the research group where they developed their algorithm. Government’s role in the Valley has been essential to its successive renewal across technological generations and diverse fields with conjoint theoretical and practical potential, driving Stanford’s academic success as well as innovation in the competitive industries of the Bay Area.

Government initiatives and programs played a key role in both regions, providing the resources to help found the venture capital industry in Silicon Valley and through revising regulations for investment, making possible the invention of the venture firm in Boston. The hip-hop musical Hamilton has revived the public role in US economic development, bringing an 18th-century national innovation and collaborative development model to the forefront of public attention, and retaining Alexander Hamilton’s image on the 20-dollar bill as well (Lind, 2012). New developments in innovation strategies and practices are invented, giving rise to an entrepreneurial university, linked to industry and government.

It is a “hidden industrial policy” (Etzkowitz and Gulbrandsen, 1999), instantiated, for example, in the fledgling network of manufacturing research and development institutions, established under President Obama. The pulling together of government, academia and industry operates like a virtual Bell Labs, producing small-scale innovations that can be widely shared (Paul, 2016) across manufacturing industries. These are merely the latest in a stream of initiatives, from the Lincoln, Hoover and Roosevelt eras, that have created a triple helix innovation model. It is spreading from Silicon Valley and Boston, inland to Dayton, Ohio, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and elsewhere, where some of the same collaborative initiatives are being taken. State economic development and innovation policies could be expanded nationally from a focus on individual firms to entire industries but direct responsibility for job creation is controversial on the federal level (Atkinson, 2016; Tuttle, 2016).

The first venture capital firm, American Research and Development (ARD), was itself a synthesis of university, government and financial industry elements and practice, an exemplary triple helix organization (Ante, 2008). The Governors of the six New England States convened a series of discussions among university–industry–government leaders, in response to a declining manufacturing economy in the early 20th century. The council they created became a platform for organizational innovation, including the invention of the venture capital firm to speed firm formation from MIT. The transfer of this financial innovation to northern California, assisted by a federal government program to expand the nascent venture capital industry in the early post-war, helped create an ecosystem of support for start-up formation and growth. University–industry–government collaboration might otherwise have been a temporary World War II phenomenon, acceptable in a national emergency but not in peacetime (Draper, 2011). Industrial decline in one region and absence of an industrial economy in the other, with the common presence of industrially oriented academic institutions with porous boundaries, provided a fertile soil for creating a new model of knowledge-based economic and social development.

Triple helix sources

A pathway from a declining industrial to an emerging knowledge-based society is created through universities, firms and governments interacting and “taking the role of the other.” In this model of interactive spheres, entrepreneurial initiatives are not only the actions of individuals who form companies in the industrial sphere. Thus, there are organizational entrepreneurial initiatives as well as individual ones. Entrepreneurs can also be universities and government organizations and entrepreneurship can take place as a collaboration of individuals and organizations in various institutional spheres.

Government and industry were the primary institutions in industrial society from the 18th century. The university is the generative source of knowledge-based societies just as government and industry were the primary institutions in industrial society. Industry remains a key actor as the locus of production, government as the source of contractual relations that guarantee stable interactions and exchange. The competitive advantage of the university, over other knowledge-producing institutions, is its students. Their regular entry and graduation continually brings in new ideas in contrast to R&D units of firms and government laboratories that tend to ossify, lacking the “flow-through of human capital” that is built into the university. The presence of an entrepreneurial university whose faculty and students actively seek out the useful results of their research is a key factor in regional innovation. Beginning within Stanford’s Engineering School, an entrepreneurial culture has spread more broadly within the university, from its electrical engineering department to computer science, to the medical school and to other universities in the region, like Berkeley and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), a specialized medical university, that had previously not seen this as their mission.

The ideal triple helix configuration is one in which the three spheres interact and take the role of the other, with initiatives arising laterally as well as bottom-up and top-down. A Swedish university liaison director once asked, “Why a triple helix; why not a ‘double helix’ of university–industry?” The answer is that it is only possible to develop university–industry relations up to a point, without considering the role of government. On the other hand, too much government control limits the source of initiative to a narrow range of officials. Finding the appropriate balance between too little and too much government has led to the creation of triple helix quasi-governance models in which actors from the three spheres, especially at the regional level, cooperatively create and implement policy initiatives.

Toward the triple helix by different routes

Beyond co-evolution of mutually interacting institutional spheres is the transition of the key spheres from a double to a triple helix. It is the introduction of the third element, one based on creatively producing and disseminating new knowledge in the form of ideas and technologies that is the “great transformation” of the current era, following the great transformation of the 18th century that created a double helix of government–industry, with its dual statist and laissez-faire formats (Polanyi, 2001 [1944]). In discussions with Rosalba Casas and her colleagues at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), it became clear that university–industry relations could not be understood in isolation. A triple helix of university–industry–government interactions was the resulting insight.

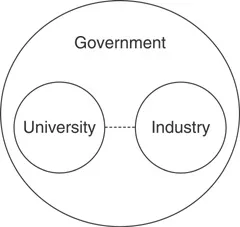

The path to the triple helix begins from two opposing standpoints: a statist model of government controlling academia and industry (Figure 1.1) and a laissez-faire model, with industry, academia and government separate and apart from each other, interacting only modestly across strong boundaries (Figure 1.2). From both of these standpoints, there is a movement toward greater independence of university and industry from the state, on the one hand, and greater interdependence of these institutional spheres, on the other. The interaction among institutional spheres of university, industry and government, playing both their traditional roles and each other’s, in various combinations, is a stimulant to organizational creativity. New organizational innovations, especially, arise from interactions among the three helices (Figure 1.3). The common triple helix format supersedes variation in national innovation systems.

Our purpose here is to elucidate the transition to a triad of equal and overlapping institutional spheres. Double helices, lacking a third mediating element, tend toward conflictual relations (Simmel, 1955). The question of the appropriate balance between industry and government, including the role of labor and capital in society, is expressed in theories and social movements that promote socialism or capitalism. A struggle between proponents of these two basic societal formats has ensued since the inception and growth of the modern state and industry, from the 18th century. Nevertheless, there is a basic commonality of laissez-faire and statist regimes despite apparently divergent formats. This structural similarity is exemplified by the interchangeability of government and industry in leading roles in various theories of reform capitalism and market socialism (Kornai, 1992).

Statist and laissez-faire regimes, the traditional competing models of social organization in modern societies, represent reverse sides of the government–industry coin. Statist societies emphasize the coordinating role of government while laissez-faire societies focus on the productive force of industry as the prime mover of economic and social development. Both formats emphasize the primacy of these two institutional spheres, albeit in drastically different proportions. Thus, strong and weak roles for government and industry are the defining characteristic of statist regimes while the reverse relationship is the basis of laissez-faire societies.

FIGURE 1.1 The statist model

Statist model

In some countries, government is the dominant institutional sphere. Industry and the university are subordinate parts of the state. When relationships are organized among the institutional spheres, government plays the coordinating role. In this model, government is expected to take the lead in developing projects and providing the resources for new initiatives. Industry and academia are seen to be relatively weak institutional spheres that require strong guidance, if not control. The former Soviet Union, France and many Latin American countries exemplify the statist model of societal organization.

The statist model relies on specialized organizations linked hierarchically by central government. Translated into science and technology policy, the statist model is characterized by specialized basic and applied research institutes, including specialized units for particular industries. Universities are largely teaching institutions, distant from industry. A central planning agency was a key feature of the Soviet version of the statist model. A decision was required from the central planning agency to arrange implementation of Institute research. Waiting on such a decision often became a blockage to technology transfer since the firms and the institutes could not arrange the matter directly, at least not through formal channels.

In the 1960s, the Argentinian physicist Jorge Sabato set forth a “triangle” science and technology policy model applying the statist model to a developing country, arguing that only government had the ability and resources to take the lead in coordinating the other institutional spheres to create science-based industry (Plonski, 1995). In Brazil, during the era of the military regime, the federal government science and technology policies of the 1970s and early 1980s, implicitly attempted to realize Sabato’s vision—government funded by large-scale projects to support the creation of new technological industries such as aircraft, computers and electronics. The projects typically included funds to raise the level of academic research to support these technology development programs. A side effect was increased local training of graduate students to work in the projects.

The role of government increases in all countries in times of national emergency. The US, for example, reorganized itself on a statist basis during the two world wars, placing industry and university into service for the state. The Manhattan project to develop the atomic bomb during the Second World War concentrated scientific and industrial resources at a few key locations, under military control, to accomplish this project (Groueff, 2000 [1967]). The recurrent calls for a Manhattan project to address such diverse problems as cancer and poverty suggest the attraction of the statist model even in countries with a laissez-faire ideology (Nelson, 2011). Indeed, the statist model can produce great results, with good leadership, a clear objective and the commitment of significant resources.

The statist model often carries with it the objective that the country should develop its technological industry separately from what is happening in the rest of the world. In Europe this model can be seen in terms of companies that are expected to be the dominant national leader in a particular field, with the government supporting those companies, such as the Bull Computer Company in France. In this configuration, the role of the university is primarily seen as one of providing trained persons to work in the other spheres. It may conduct research but it is not expected to play a role in the creation of new enterprises.

Even in France, the classic statist regime, much of these expectations have changed in recent years. Efforts have been made to decentralize elite knowledge-producing institutions from Paris in order to create other alternative sources of initiative. Although not yet at the level of the German Lander or the American state government, a new level of regional government gains resources and is able to take its own initiatives. Start-up firms, initially offshoots of military programs, begin to take on a life of their own.

Change in statist societies is impelled by need to speed up the innovation system by introducing new sources of initiative. Bureaucratic coordination concentrates initiative at the top and tends to suppress ideas that arise from below. Lateral informal relations across the spheres may partially override formal top-down procedures as in the former Soviet Union. However, such working around the system was typically confined to relatively limited initiatives. When there was a need to undertake larger-scale initiatives, the way was often blocked, outside of the military and space spheres that were given extraordinary priority in the Soviet Union.

Laissez-faire model

Another starting point for the triple helix model is separation among institutional spheres. Ideology and reality often diverge, with the spheres operating more closely together than expected. In the US, for example, skepticism of government often obscures the emergence of the triple helix. In reality the institutional spheres are closer together than is commonly held, but accepted US belief is the model of government, industry and academia operating in their own areas without close connections.

In this model, the university is a ...