![]()

Part I

Mirrors and Myths

![]()

Chapter One

Mirrors and misplaced identities

“The greatest healing is to know who you are”

(Mooji, 2011)

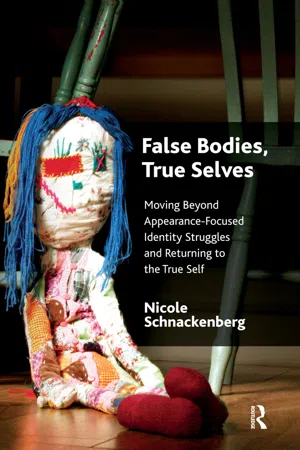

A dear friend of mine, whose beautiful artistry appears on the front cover of this book, once gave me a homemade patchwork doll. I was instantly mesmerised by it. It had been lovingly and painstakingly sewn together by hand using old, discarded pieces of scrap material and loose cuttings of thread. It looked haphazard, captivating, strangely beautiful. The more I looked at my quirky little gift the more I recognised myself in those sewn together pieces of cloth. For most of my life I had been a patchwork person, a marionette made up of gathered scraps of other people’s ideas and expectations. Painfully unable to placate or to please, I had squirrelled away other people’s perceptions and desires about who I should be as a child, sewn them together and made a person out of them, a person other people called “Nicole’”, a person I could barely even recognise. The shreds of my true Self were left in rejected tatters. The Germans have a beautifully onomatopoeic word for this: Zerrissentheit, meaning “torn-to-pieces-hood”.

I had become, as Donald Winnicott, the pioneering English paediatrician and psychoanalyst, called it, a false self (Winnicott, 1965). And I was certainly not alone. As I began to scan my periphery, I observed the tragic annihilation of people’s true needs and desires in almost every direction I looked. I began to see, beneath so many smiles, a deep brokenness, a gaping void, a tragic loss of Self.

It is this move away from the true Self, in the context of appearance-focused identity battles, which will concern our discussion for the entirety of this book. It is my firm conviction that appearance struggles arise out of the pain of living as a false self and can, therefore, reach a resolution by allowing the true Self to re-emerge.

Many of us begin our day by looking into the mirror. We assume that what we see there is our self. Yet, it continues to remain unclear as to how we recognise our own image, known in scientific circles as visual self-recognition. Jacques Lacan believed that human infants recognise themselves in a mirror from the age of about six months old and from then on view themselves as an object that can be viewed from outside of themselves (apperception). He called this the “mirror stage” (Lacan, 1977). More recent research suggests, however, that we only begin to recognise our own reflection between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four months (Nielsen et al., 2003). We are not alone in this ability to recognise our own image. In a classic experiment, Gallup (1970) found that chimpanzees are also capable of self-recognition, since they are able to use mirrors to direct their behaviour towards an otherwise unseen novel mark placed upon their face. More recent studies have found that the only other primates who share this capacity are the apes (Posada & Colell, 2007).

While Lacan initially proposed that the mirror stage was simply part of an infant’s development, his theory later evolved. He no longer believed the mirror stage to be a singular pivot in the life of a small child, but, rather, viewed it as a permanent structure of subjectivity, as something he termed the paradigm of the imaginary order. The basis of the imaginary order is that the ego is formed in the mirror stage, which occurs through identification with the viewed image. Our ability to recognise ourselves and identify with the recognised image is thought to be especially fundamental to the awareness of being a self among others like us. We can then build more complex forms of self-identity on to this awareness, such as a diachronic (over time) sense of self. Our bodies change significantly over the course of our lives, with each life stage altering multiple facets of our appearance. As we age and our appearance changes, we must adapt to the altered reflection in the mirror in order to sustain recognition of the changing face and body that we see there.

There are many reasons why we might look into the mirror. Perhaps we are checking our hair or deciding if our shoes look as if they are having an argument with the rest of our attire. These are trivialities, yet looking into the mirror can also be anything but a trifling experience. Perhaps we are looking to derive our sense of self-worth from the reflection we see. Perhaps we are checking whether we actually exist at all. The human body and its appearance are heavily value laden and imbued with meaning. The body is a

site of birth, growth, ageing, and death, of pleasure, pain and many things . . . an object of desires . . . a bearer of features . . . a biological machine that provides the material preconditions for subjectivity, thought, emotion and language. (Cromby & Nightingale, 1999, p. 10)

When we look into the mirror we are seeing a rich web of experience, overlaid with our current ideas and notions about who we have been and who we think we now are.

Mirrors have featured heavily in myths and legends and in children’s literature across time. They also abound in superstitious thinking across the ages. In some ancient cultures, it was considered necessary to cover all the mirrors in the house when a loved one died under difficult circumstances, since people believed that the spirit of the dead person would linger on, looking for a body to possess in order to complete any unfinished business. Breaking a mirror, as many of us will know, is said to carry bad luck for seven years, a superstition traceable to the Romans, who were actually the first to create glass mirrors. The Romans, along with the Greek, Chinese, African, and Indian cultures, believed that a mirror had the power to take away part of the gazer’s soul. Some cultures have long exclaimed that if you look into a mirror often enough you will see the devil, perhaps by way of warning people against the so-called sins of vanity and self-obsession.

In Greek mythology, one person who might have done well to heed this advice was Narcissus. Narcissus was an exceptionally handsome young man who constantly spurned the affection of the adulating nymphs. One day, desiring a drink, Narcissus took himself to a clear pool of water wherein he saw his reflection and promptly fell in love with it. Since he could not gain the love he felt, he remained pining at the pool and died there. When the nymphs heard of his tragic fate, they went down to the pool and found no body, but a flower at the spot where Narcissus died, the flower that now bears his name. Another Greek myth famously featuring a mirror reflection is that of Perseus, one of the first heroes of Greek mythology. To avoid looking into Medusa’s eyes and, thus, being turned into stone, Perseus viewed Medusa through a reflection in the mirror and was, thereby, able to cut off her head and defeat her.

The fauna of mirrors is a rather interesting superstition, springing from an ancient Chinese myth, which claims that behind every mirror there is a completely different world, first described in a story by Jorge Luis Borges entitled “Fauna of mirrors” (Borges, 2006). Such thinking has also been adopted by more modern writers, including Lewis Carroll in Alice through the Looking Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Alice, while pondering what the world is like on the other side of a mirror’s reflection, climbs on to the fireplace mantel and pokes at the wall-hung mirror there. To her immense surprise and delight, Alice finds that she is able to step through the mirror and into an alternative reality, into a world in which she is adoringly crowned as a queen before waking up to the realisation that it has all been nothing more than a dream.

In Snow White, we also find the legend of the mirror possessing other-worldly abilities, with the wicked step-mother summoning the spirit in the mirror to tell her who is the “fairest one of all” in order to reassure herself of her own good looks. This legend is based on scrying, which, in its basic form, is the belief that a young woman will see her future husband if she applies focused concentration and asks who “is the fairest one of all?” while combing her hair by candlelight at midnight in front of the mirror. Mirrors have long been used as a means of divination, an art known as catoptromancy. In this ancient practice, it is said to be possible to divine the past, present, and future by gazing into the surface of a mirror, usually positioned to reflect the moonlight. Catoptromancy was practised for many centuries and is the origin of much folklore. Père Cotton, confessor to King Henry IV of France, reputedly used a mirror to reveal plots against the King. It is also known that Pythagoras, the famous Greek mathematician, frequently practised catoptromancy during a full moon.

In my favourite fairy-tale, The Snow Queen, by Hans Christian Andersen, an evil troll makes a magic mirror that has the power to distort the appearance of anything reflected in it. While failing to reflect all the good and beautiful aspects of the gazer, it nevertheless magnifies all the dark and ugly qualities, making people seem far worse than they actually are. The trolls are so delighted with their creation that they wish to carry the mirror into heaven to make fools of the angels. As they lift the mirror higher and higher, it begins to shake, eventually shattering into millions of tiny pieces and falling back down to earth. The splinters are blown asunder by the wind, entering into people’s hearts and eyes, freezing their hearts over like ice and rendering their eyes blinkered like the troll-mirror itself; they are now only able to see the dark and ugly in everything.

Looking into the mirror and perceiving only the dark and ugly aspects of the self is sadly not an occurrence restricted to the realm of fairy tales. For growing numbers of people all over the world, the mirror can become such a window into self-loathing, abandoned self-worth, and disintegrating self-respect. A report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Body Image (2012) found that girls as young as five are worrying about their size and appearance, and that one in four seven-year-old girls have tried to lose weight at least once. Heartbreakingly, 34% of adolescent boys and 49% of girls surveyed were found to have been on a diet to change their body shape or lose weight and 60% of participating British adults reported feeling ashamed of the way they look. These figures are hardly surprising given that, according to the British Social Attitudes Survey conducted in October 2014, almost half of all adults (47%) think that “how you look affects what you can achieve in life”, and one third (32%) agree with the statement “your value as a person depends on how you look” (Government Equalities Office, 2014). Such messages permeate our media, with 75% of those surveyed by the All Party Parliamentary Group viewing media, advertising, and celebrity culture as being the main social influences on body image.

Western culture would appear to be providing the ideal conditions for difficult life experiences to seek resolution in appearance battles. By the end of the twentieth century, popular culture had begun to identify bodies as sites of commodified forms of health and beauty, offering glamorous identities and powerful sexuality, though at a price. Since then, we have been increasingly drip-fed the myth that happiness can be constructed via the manipulation of our physical appearance. Many of us, subsequently, have dabbled or thrown our selves headlong into our beauty projects, hoping to soothe and negate any emotional pain, most likely rooted in our childhood, through the modulation of our flesh. As we lose weight, increase our musculature, clear our skin, and increase our cup size, Western culture takes a standing ovation, thus legitimising further action. It is amazing, for some of us, just how deep the rabbit hole can go.

It is disadvantageous to their perpetuation for capitalist societies to extol the acceptability and beauty of our bodies, since this would negate any need for the purchase of goods. It is far more lucrative to sell the “you must look a certain way in order to be happy” myth, and to encourage us to change and “enhance” our bodies through diets, cosmetics, surgery, and other such means. Notably, cosmetic surgery rates in the UK have increased by almost 20% since 2008 to an estimated value of £2.3 billion, an upsurge that has been largely attributed by researchers to advertising and irresponsible marketing ploys. By insidiously fostering the belief that we can become better, more acceptable, and increasingly loveable by altering our physical form and appearance, we are persuaded to buy into the multiple industries whose survival depends on us spending money on their products and signing up for their programmes.

Too many of us have decided that if we are seemingly imperfect it must be our fault. If we are too large by society’s standards, it is because we have not dieted enough; if our hair is too frizzy, it is because we have not searched earnestly enough for the right products to smooth it down; if we have dark rings under eyes we should be ashamed for not covering them up with one of the plethora of concealers sitting expectantly on the chemist’s shelf. We have heedlessly and tragically swallowed the cultural myth that it is not only our business to make ourselves look good, but also our obligation to be beautiful. As Martina Cvajner writes, having interviewed Italian women about their perceptions of their appearance,

For my informants, to “take care of their appearance” did not necessarily mean pursuing one’s natural physical beauty. Rather, beauty was something to be constructed. The body, in other words, is a canvas that counts—to define if and whether a person is a woman— not for its intrinsic qualities but for the degree of effort and creativity of what is being painted on it. If you take care of yourself, you are a woman. (Cvajner, 2011, p. 364)

This sense of being agents of our own beauty is tangled up in our experience of our body image. Such body image develops partly as a function of culture in response to cultural aesthetic ideals (Rudd & Lennon, 2001). We cannot really talk about body image, therefore, without considering the society within which a person is situated. In current Western culture, thinness and attractiveness are seen to be highly desirable physical traits for women, while men are lauded for being muscular and handsome. These notions of attractiveness are intrinsically wrapped up in experiences of self-worth. Such perceptions are reinforced through evaluations of, and comparisons to, others, including family members, peers, and media images. Comparison to idealised images in the mass media, for example, has been shown to create and reinforce a preoccupation with physical attractiveness (Groesz et al., 2002).

Western culture’s current standard of attractiveness for women, as portrayed in the media, is slimmer than it has been in the past and, hence, is unattainable by most women (Hausenblas et al., 2002). Many women, however, subliminally absorb the thin ideal and could come to berate themselves for any failure to morph into it. Such ideation wreaks havoc, as one might imagine, on self-esteem and self-worth. Ninety-five per cent of women are estimated to diet at least once in their lifetime (Grogan, 2008), a practice which has become a cultural norm in many Western societies and yet is life-threatening at worst and painful to some degree at best. The body reacts very strongly to a shortage of food, as we shall see in Chapter Three, which can result in significant compromises to the person’s physical, emotional, and psychological health. Comparisons to media images have been shown by Heinberg and Thompson (1995), among others, to trigger depression, anger, and distortions related to body image. In terms of media images of men, research has found that men are now portrayed as more muscular than in the past (Leit et al., 2001), with almost one third of British men wanting to look like the models they see in magazines (Diedrichs et al., 2011).

While some advertising does portray relatively “ordinary” or “average” people in everyday situations, most advertising presents an unrealistic or idealised picture of people and their lives (Richins, 1995). Sadly, the level of beauty and physical attractiveness presented in media images is characteristic of only a tiny proportion of the population. Yet, the message we are perpetually sold is that this level of beauty and attractiveness is the norm, or, at least, something towards which we can realistically strive. The digital manipulation, or “airbrushing”, of such media images is likely to further exacerbate this reality gap.

Cultivation theory posits that consistent media representations construct an alternative reality: in this case, a reality in which the world is populated by slim, attractive women and handsome, toned men. Due to the pervasiveness of these images, an upward shift of people’s personal image expectations can occur (Blowers et al., 2003). In an innovative study by Hargreaves and Tiggeman (2003), the effects of appearance-related television commercials and non-appearance-related television commercials on body dissatisfaction among adolescent girls were analysed. The girls exposed to appearance-related commercials became more dissatisfied with their own appearance than those who were exposed to non-appearance-related commercials. Overall, findings indicated associations between greater body dissatisfaction and more frequent television viewing. In another study, Myers and Biocca found that women’s perceptions of their bodies changed after watching less than thirty minutes of programming or advertising, a finding which suggests that our body image is highly elastic and susceptible to outside influence. They concluded,

Television images that are fixated on the representation of the ideal female body immediately led the female subjects to thoughts about their own bodies. This in turn led to the measurable fluctuations and disturbances in their body image. In their mind’s eye, their body shape had changed. (Myers & Biocca, 1992, p. 126)

These influences can be understood within the concept of social comparison theory, as outlined by Leon Festinger (1954). Social comparison theory postulates that people are driven to acquire a precise assessment of themselves by discerning their abilities and opinions in comparison to the individuals around them. According to Festinger, people obtain a sense of validity and clarity by comparing themselves in specific domains against an objective benchmark provided by the people with whom they are comparing themselves. Comparing ourselves with someone similar produces more accurate appraisals, while comparing ourselves to more dissimilar others creates less accurate assessments. Due to the overwhelming societal preference for thin, beautiful women and handsome, muscular men, most of us, therefore, are comparing ourselves with people highly dissimilar to ourselves, resulting in less accurate appraisals of our own attractiveness and body shape. Indeed, it has been estimated that less than 5% of the population could ever realistically attain to the body image ideals presented in the media.

While media attention and societal discussion focus primarily on the health risks of being overweight, the health risks of being underweight (which are considerable) receive far less attention. Research conducted by Flegal and colleagues (2005), for example, found that being underweight was associated with an estimated 33,746 excess deaths (above the usual mortality rate) in the year 2000 in the United States, despite the very small percentage (2.7%) of the subject pool in this category. Con versely, many people classed as being overweight live longer and healthier lives than people categorised as normal weight (Flegal et al., 2013) and around 19% of people classed as obese are metabolically healthy (Hankinson et al., 2013). With...