![]()

Part 1

The Cross-Cultural Sme Environment

Cross-cultural studies seek to describe and compare phenomena in different cultural, social and economic environments. Cross-cultural studies focusing on small businesses are based on different kinds of data, from official statistics to research reports, and the rich literature of cross-cultural studies which encompasses a wide variety of perspectives and aspects. An individual author’s own background, based on knowledge and experience gained in different cultural settings, makes any book a personal document and more or less different from other similar publications.

Official statistics are available from international organizations and statistical offices of individual countries. However, formal faults and shortcomings reduce the usefulness of such statistical information. These arise from inappropriate data collection mechanisms, inconsistency in definitions and uncertainty about original data accuracy. A considerable amount of research and literature about small and medium enterprises in international contexts makes reference to such statistics without mentioning or even being aware of its potential lack of reliability.

The study of facts and phenomena in other cultures requires that activities and events are understood and can be accounted for. Language is important not only as a means of communication but also in defining the names of subjects and activities. As the following extract demonstrates, local names which are deeply culturally-rooted cannot always be translated into another language while keeping their original meaning: distortion of words and meanings becomes a complication in cross-cultural studies. The extract goes on to consider African traditional political thought using terms not of African origin but that come from foreign countries, particularly from Europe: the problem arises from having to formulate concepts through translations.

In religion, for instance the Christian missionaries with the assistance of their few African proselytes translated “God” into all sorts of words. In Acholiland, God was translated as Jok, although, as we have been told, the term Jok does not mean the “High God” which the white missionaries had in mind. The term normally means the God of a particular Acholi chiefdom so that the Jok of an Acholi clan or Chiefdom A is not necessarily the Jok of the Acholi clan or Chiefdom B. For instance, the Jok of the Koch Chiefdom, one of the largest chiefdoms in Acholi, is Lebeja; whereas the Jok of Padibe Chiefdom is Lan’gol. To make it even more complicated, we find that the Payira Chiefdom has seven clans and each of these clans has got its own Jok. The seven Jogi of the Payira people, representing the seven clans of Paiyira are Jok Kalawinya, Jok Kilegaber, Jok Byeyo, Jok Ona, Jok Lwamwoci, Jok Ang’weya, and Jok Goma. In other words there is no one Jok for all the Acholi clans; and, consequently, Jok cannot be said to represent the Christian High God who is supposed to be the God of all men, including, of course, the Acholi in northern Uganda.

So it is with the African traditional political thought. We are faced with the problem of having to apply European terms to explain concepts which are uniquely African; we have to formulate concepts of African experiences and thought-systems in terms of European languages and philosophy. The result of this is that while we may be able to conceive and appreciate African ideas on politics, economics, religion or culture, we may be unable, because of our inadequacy in the English or French language, to express these ideas articulately and meaningfully. When this happens, we may then conclude that the African ideas are inadequate, poor or even barbarian. On the other hand, while we recognise the problems involved in the use of European languages in explaining African concepts, we cannot all the same avoid using these languages in discussing African political thought because in Africa we do not have one single language in which all Africans can exchange their own ideas and their own experiences in their own language or thought-system. That is why, while a Muganda can sincerely enjoy a joke with an Englishman, he may not be able to enjoy the same joke if it is presented by a Matabele with whom he shares the African continent. (Mutibwa 1977)

This rather long quotation from African Heritage and the New Africa by Phares Mukasa Mutibwa of Makerere University in Uganda spells out a picture of African culture at a detailed level that is unusual in general descriptions. Similarly-detailed levels are, of course, not necessary every time a cultural phenomenon is to be described. The dilemma is, however, that we cannot know how much detailed understanding is necessary to fully grasp a cultural phenomenon. It is possible that cultures are incommensurable and it is therefore not possible to fully understand unless one is part of that particular culture.

Chapters 1 to 5 are characterized by a macro perspective which assumes enterprises are parts of a development process taking place in their operating environment. Since a process requires a structure that is fixed during the time frame of interest, this structure is primarily defined by the legal system, the political system and traditions and values from the culture. Within this structure different processes take place, one such process being the development of the small business sector. The parameters that may vary in this process include management styles, employee attitudes and the strategies of the firms, all being subject to the structure that provides the limits within which the process parameters may vary. The picture of structures given in this first part is intended to provide the background for Part 2.

Chapter 1 presents a picture of small business in different parts of the world in terms of definitions, demography and various statistical data. Growth of the SME sector is discussed and the small business sector of four is scrutinised in some detail.

Chapter 2 gives an overview of economic development, and includes a discussion about different measures of development. After an initial discussion of SMEs and economic development (expanded in the next chapter) a number of influential development researchers are profiled.

In Chapter 3, the question is raised as to the extent small firms contribute to economic development. The concept of added value is introduced as an important parameter for the discussion of small business growth.

Chapter 4 discusses entrepreneurship and asks if the entrepreneur and the small business manager play the same roles. The motives for starting up a small business in different cultures are discussed, as well as the nature of entrepreneurship in cross-cultural environments.

Chapter 5 considers whether Government is facilitator or ‘trouble-maker’ for SME growth. What are the roles of Government in supporting the SME sector, and why is it that otherwise laudable interventions can have counterproductive effects?

Reference

Mutibwa, P. M. (1977) African Heritage and the New Africa. Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau.

![]()

1 Small Business in the World

Introduction

‘Small business’ is not a homogenous concept and cannot be treated as such. In many countries, small business is all business, whereas in others the small business sector is distinct from large firms. Given the ambition of this book to give an overview of small firms, their operational environments and their management in a cross-cultural context, the choice of aspects and perspectives become critical. The external perspective dominates in the first part of the book, where small firms are seen in their respective contexts characterized by political systems, economic sectors and competence levels. The role of governments and public administration differ widely between regions and countries in respect of industry support. While insufficient access to risk capital, hindering bureaucracy, bribery and corruption and inefficient legal and infrastructure systems form part of the business reality for many small firms in many countries, the corresponding situations for small business in Europe, North America and Japan are both different and more supportive. It is inevitable that the conditions for efficient management depend crucially on the influence of different factors prevailing in different parts of the world.

The dominance of the service sector as contributor to the national economy in high-income countries1 creates business opportunities and has been important for entrepreneurship and small business growth. In low- and middle-income countries, where the agriculture and manufacturing sectors are significant for the domestic economy, the production of goods is important, and many small firms belong to the manufacturing sector. Although in discussing small business this book does not distinguish between different industry sectors, examples and case studies are drawn from many different sectors. However, the variety and types of firms are such that it is impossible to include all of them in one book. In the manufacturing sector, firms range from those of low technological level relying on manual labour, to highly advanced firms with fully automated production processes. Although different types of firm in different environments have different needs in respect of management theories and tools, a more generic set of business theories is also useful in widely different cultural contexts.

Questions and aspects related to the growth of the small business sector is a dominant theme throughout Part 1, as well as in Part 2. The focus is motivated not only by the significant interest that has been placed on small firms for their expected contribution to job creation and economic growth, but also by the disappointment and growing mistrust in small firms as engines of growth in the economy. This view requires a shift in perspective from the external macroeconomic perspective, where small firms can be assessed in their contribution to society growth, to the internal perspective, where performance and management of individual firms are viewed based on their own individual conditions.

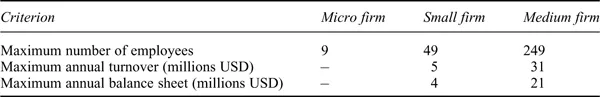

‘Small business’ is an ill-defined concept, not least because ‘small’ is a relative term. A small business in a Western country may be regarded as a medium-size or even a big business in a developing country. A small business can be anything from a one person bicycle repair shop in a street in Hanoi to a high-tech manufacturing company in Stockholm with around 50 employees. It can be officially registered or not, it can be an entrepreneurial activity that has just started or it can be a stable business that has been operating in the market for many years. The European Union (EU) has adopted a standard definition that classifies small and medium firms into three categories according to number of employees and annual turnover. Firms with less than ten employees are thus classified as ‘micro enterprises’, firms with between ten and 50 employees are referred to as small and those with between 50 and 250 employees as medium-sized enterprises; firms with more than 250 employees are large enterprises. Table 1.1 summarises the EU definition, also used by the World Bank and United Nations.

Table 1.1 Definition of small and medium enterprises in the European Union

Referring to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as a group can give the impression that firms have essential features in common. In fact, many medium-size firms have more in common with the lower end of large enterprises than with small firms. Above a certain size, firms tend to develop organizational structures and hierarchies that are characteristic of larger firms. There is no definite measure when this happens, but at around 20—25 employees ad...