![]()

1

THE PROGRESS OF EVOLUTION

No-one should make sweeping claims concerning evolution in fields outside the biological world without first becoming acquainted with the well-seasoned concepts of organic evolution and, furthermore, without a most rigorous analysis of the concepts he plans to apply.

Mayr, The growth of biological thought. Copyright © 1982 by Ernst Mayr.

Do societies, or cultures, evolve? It all depends, you will say, on what I mean by evolution. An anthropologist would probably interpret the question as one about progress, thus: ‘Is it reasonable to envisage an overall movement from the primitive to the civilized in human modes of life?’ Most likely the anthropologist’s answer would be negative, but even were it affirmative he would surround it with qualifications—if only to avoid the charge of ethnocentrism. But how would a biologist construe the question? Most biologists consider evolution a proven fact, yet many balk at applying the idea of progress to living nature, just as do anthropologists in relation to culture and society (Lesser 1952:136–8). According to one recent definition, designed to embrace social phenomena within a biological framework, evolution is ‘any gradual change’ (Wilson 1980:311)—a definition that must strike anthropologists (and perhaps many biologists too) as too broad to be useful. Surely all societies are changing all the time. But paradoxically, so long as anthropologists were content to regard their subject as the study of ‘primitive’ forms, with the implicit connotation that others had progressed to a more advanced state, these forms were treated as essentially changeless. Are we, then, to regard evolution as progress without history, or as history without progress? These alternatives can be traced to the two major exponents of evolutionary thinking in Victorian England: Herbert Spencer and Charles Darwin. My purpose in this chapter is to isolate the critical points of difference between the two perspectives. Their clarification is essential to my subsequent project, which will be to link the difference to an opposition between the social and the cultural dimensions of human experience.

It is still widely believed that the ‘evolutionism’ that dominated nineteenth-century social thought was a unitary paradigm that owed its foundation to the publication, in 1859, of Darwin’s The origin of species. This paradigm is largely a fabrication constructed and maintained by those who claim to reject it (Hirst 1976:15). There was not one theory of social evolution but many, and all stemmed from ideas current long before Darwin. As Burrow has remarked, ‘The history of Darwin’s influence on social theory belongs . . . to the history of the diffusion of ideas rather than of their development’ (1966:114). And as we shall see, this diffusion did not take place without a great deal of distortion. These facts have been pointed out often enough in the literature.1 Their obfuscation can be put down in part to the belief amongst some biologists and much of the lay public that Darwinian theory provides the key not only to the evolution of life, but also to the past and future of humanity. Many distinguished scientists, whose careful consideration of the facts of nature leads them to reject the idea of inevitable ascent from ‘lower’ to ‘higher’ forms, have thought fit to pronounce on the progress of mankind in tones reverberant with the ideals of bourgeois enlightenment, and backed by no solid evidence whatsoever. Darwin did this (see Bock 1980:37–60), and so do many of his latter-day sociobiological followers (e.g. Wilson 1978). Anthropologists have good reason to protest against such naïve speculations. Yet if their protestations are to carry any weight, and if they are to produce a theory of social or cultural evolution that avoids the pitfalls identified by biologists decades ago, they must be clear about the epistemological status of the concepts they intend to apply. For this reason Mayr’s admonition (1982:627), with which I headed this chapter, must be taken seriously. In its fulfilment, we shall inevitably have to stray rather far into the realms of biological thought. But let me begin with a word about the origin of ‘evolution’.2

The verb ‘to evolve’ comes from the Latin evolvere, which literally means to roll out or unfold. Already in the seventeenth century it was being extended metaphorically to refer to the revelation or working out of a preformed idea or principle. However, this usage was occasional and unsystematic (Williams 1976:103). The history of ‘evolution’ took an odd turn when it became the central concept of the theory of preformation in embryology, advocated by Charles Bonnet in 1762. According to this theory, every embryo grows from a tiny image of itself—a homunculus—present in the egg or sperm, which in turn contains an even tinier image of its future progeny, and so on. By extension, the very first homunculus—supposedly inhabiting the ovum of Eve—must have contained a programme for the development of all future generations, which would appear in the course of time as the homunculi were ‘unpacked’ one after another (Gould 1980:35, 203). However bizarre the idea, it did conform to the original, literal meaning of evolution (Bowler 1975:96–7). By the middle of the nineteenth century, Bonnet’s theory of preformation was defunct, but the concept of evolution had been revived in quite another guise by that dinosaur of Victorian philosophy, Herbert Spencer. The connotation had ceased to be one of the unfolding or unpacking of qualities immanent in the thing evolving and had become linked instead to the idea of progressive development towards an enlightened future. As a prognosis for mankind, this was hardly a new idea in Western philosophy, for its roots go back at least to the early seventeenth century (Bury 1932:35–6; Bock 1955:126). It reached a climax in Condorcet’s Progress of the human mind, published in 1795, which in turn became the inspiration for the work of Saint-Simon and his disciple, August Comte. From Comte, Spencer admitted to having adopted the term ‘sociology’ but little else (Burrow 1966:189–90; Carneiro 1967:xxi–xxii, xxxii). Despite their differences, which were indeed profound, both Comte and Spencer sought to establish natural laws by which human civilization might be ordained to progress (Mandelbaum 1971:89). It was Spencer’s self-proclaimed achievement, however, to have welded a conception of the development of society (‘the superorganic’) into a grand synthesis that embraced the temporal progression of all organic and inorganic forms as well.

The intellectual climate of Spencer’s day was particularly conducive to such a synthesis. At that time the dominant concern was to discover and explain how things had come to be as they are, a concern that grew in proportion to the steady decline in the authority of orthodox religious doctrines of creation, and to the concomitant advance of natural science. Thus the reconstruction of human development in its various aspects came to be conceived as but part of a wider enterprise, the reconstruction of life, which in turn was to be fitted into a picture of the history of the earth and even of the entire cosmos. Spencer found the inspiration for his synthetic philosophy through his acquaintance—at second hand—with the work of the German embryologist von Baer (1828), who had observed that every stage in the development of an organism constitutes an advance from homogeneity of structure to heterogeneity of structure (Mayr 1982:473). In an article entitled ‘Progress: Its law and cause’ (1857), Spencer endeavoured to show that ‘this law of organic progress is the law of all progress’ (1972:40). With one sweep of his cosmic pen, everything from the earth through all forms of life to man and human society was brought within the scope of a single principle of epigenetic development, as applicable in astronomy and geology as in biology, psychology and sociology. Shortly after the appearance of this article, Spencer decided to substitute ‘evolution’ for ‘progress’, on the grounds that the latter entailed too anthropocentric a vision (Carneiro 1967:xvii; Bowler 1975:107–8). His celebrated definition of evolution, appearing in First principles (1862), ran as follows: ‘Evolution is definable as a change from an incoherent homogeneity to a coherent heterogeneity, accompanying the dissipation of motion and integration of matter’ (1972:71). The grandeur of this conception captured the Victorian imagination. Before long, Spencer had a considerable following, and evolution had become a catchword. It still is, yet Spencer and his voluminous works are today all but forgotten. Although his intellectual death was pronounced almost fifty years ago by Talcott Parsons (1937:3), there are faint signs of a contemporary resurrection (e.g. Parsons 1977: 230–1; Carneiro 1973).

How are we to account for this curious turn of fate? In brief, the concept of evolution was extended—largely through the efforts of Spencer himself—to cover what Lamarck had called the ‘transformism’ of living forms, and the process to which Darwin came to refer as ‘descent with modification’. Spencer remained throughout his life a committed Lamarckian (Freeman 1974), a point of some significance to which we shall return in Chapter 6. But he also became a strong advocate and publicist of Darwin’s views, which he regarded as accessory to his own. For the principle of natural selection he substituted the catch-phrase ‘survival of the fittest’, which he had first hinted at in 1852, seven years before Darwin published The origin of species. The co-discoverer of natural selection, A. R. Wallace, later persuaded Darwin to adopt Spencer’s phrase, believing that it would be less conducive to the misinterpretation of nature as a wilful agent selecting forms to suit its purposes (Carneiro 1967:xx; Mayr 1982:519). Yet in the doctrine of ‘survival of the fittest’ the theories of Darwin and Wallace were equally exposed to distortion, for the essential connotation of differential reproduction was obscured (Goudge 1961:116–18). It was all too easy to regard the ‘fittest’ not as those who left relatively more offspring but as those who managed—with ‘tooth and claw’—to eliminate their rivals in a direct competitive struggle. Moreover, to avoid tautology, ‘the fittest are those that survive’; the victorious parties were considered a priori to be the most advanced on a general scale of progress. For this distortion, Spencer and subsequent ‘Social Darwinists’ must be held principally responsible. In reality, the process of variation under natural selection that Darwin invoked to account for the diversification of living forms, far from providing confirmation from within the field of biology of Spencer’s evolutionary ‘laws’, rested on principles wholly incompatible with the axiom of progressive development inherent in these laws. Today Darwinian theory has triumphed, in a form remarkably close to the original, and more or less purged of its Spencerian accretions (Ghiselin 1969). It has not, however, been stripped of the title Spencer bestowed on it—‘the theory of evolution’ (Bowler 1975:112–13). Therefore, to understand the difference between the social evolutionism of the nineteenth century and the biological evolutionism of the twentieth (as well as contemporary theories of cultural evolution constructed on the biological model), we must look more closely at the logical premisses of Darwin’s theory of descent with modification.

The most fundamental axiom on which Darwin built his theory was not the progression but the variability of living forms. Without variability there could be no natural selection, since there would not be the material on which it could operate. In fact, Darwin’s conception of variability contained three components, two of which were not original to him. First, there was the idea of continuity or insensible gradation. Darwin himself refers to the precept natura non facit saltum (nature never makes leaps) as ‘that old canon in natural history’ (1872:146, 156). It had indeed been around for a long time, in the form of the classical doctrine of the ‘Great Chain of Being’. According to this doctrine, which enjoyed widespread popularity from the Renaissance until the late eighteenth century (Oldroyd 1980:9–10), all the multitudinous forms of life are locked in place along a grand scale from the lowliest to the most exalted (human beings), such that not a single position in the scale remains unfilled (Bock 1980:10; Mayr 1982:326). Thus Leibniz, in a letter published in 1753, spoke of the ‘law of continuity’ that requires ‘that all the orders of natural beings form but a single chain, in which the various classes, like so many rings, are so closely linked one to another that it is impossible for the senses or the imagination to determine precisely the point at which one ends and the next begins’ (cited in Lovejoy 1936:145). If there is an evolution in such a system, it consists in the forward displacement of the entire chain, such that the hierarchical relations between its parts are preserved intact. Beings do not give rise one to another, as the less advanced to the more advanced; the monkey of the future—as Bonnet conjectured—may have the intellect of a Newton but will still be a monkey and not a human being, occupying its appointed place between mankind and beings lower on the scale, all of which will have undergone a concurrent advance (see Foucault 1970:151–2).

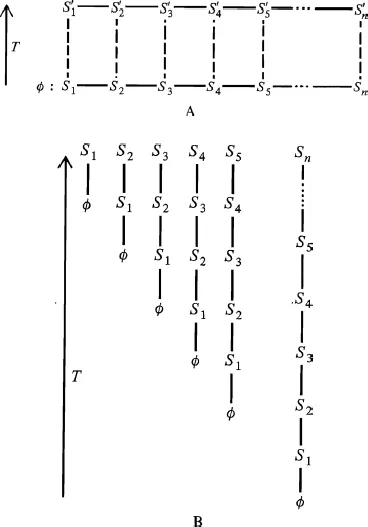

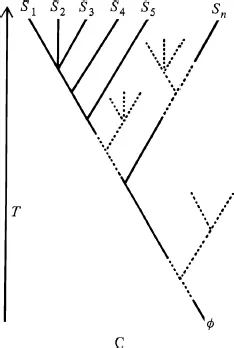

The idea that time, far from carrying forward the scale as a whole is rather intrinsic to its very constitution, as the movement by which its successive elements are revealed, is quite a different one. It was anticipated as long ago as 1693 by Leibniz, who nevertheless remained unaware of the challenge it posed to his own philosophical system (Lovejoy 1936:256–62). But it was that most maligned figure in the history of biology, Jean Baptiste Lamarck, who went the furthest in what Lovejoy has called ‘temporalizing the great chain of being’, by setting it in motion, replacing an essentially static picture of living nature with one of continuous flux. In Lamarck’s conception, organisms could ‘work their way up’ the scale as if on a moving staircase. As fast as some reach the top of the scale, others are supposedly being created at the bottom—by ‘spontaneous generation’—to ascend in their turn (see Fig. 1.1). Thus the chain is, strictly speaking, no longer one of being but one of becoming, defining not a series of fixed and unalterable positions but a trajectory of advance. However, superimposed on and complicating this linear movement is a ‘lateral’ process of adaptation to particular environments. Thus for Lamarck, the representatives of a species are undergoing constant transformation, both as they progress up the scale and as they encounter diverse physical conditions (Boesiger 1974:24–5). In his understanding of temporal variability and adaptive modification, Lamarck has perhaps as good a claim as Darwin to have founded the theory of evolution, as it is understood in contemporary biology (Mayr 1976; 1982:352–9). But when Lamarck’s works were published, in the first two decades of the nineteenth century, ‘evolution’ still carried the connotation—from Bonnet—of preformation. And Bonnet was a staunch advocate of the fixity of species in the chain of being. That is why Lamarck chose a quite different concept—that of transformism—to characterize his theory.

The ideas of continuity and temporality are both crucial components of the Darwinian conception of evolution. Yet for Darwin they had connotations quite different from those they had for Lamarck and his predecessors. For the continuity of ‘descent with modification’ is not a real continuity of becoming but a reconstituted continuity of discrete objects in genealogical sequence, each of which differs minutely from what comes before and after. Thus the life of every individual is condensed into a single point; it is we who draw the connecting line between them, seeing each as a moment of a continuous process. And consequently, time is not intrinsic to evolution but is conceived as an abstract dimension in which these points are plotted; instead of an inner time that actively brings forth or reveals new forms in progressive succession, we have an outer time that provides a backcloth against which the whole parade of forms is to be projected. Gillespie is right to claim, in these respects, a complete hiatus between Lamarckian and Darwinian conceptions of the evolutionary process, for what Darwin did ‘was to treat the whole range of nature which had been relegated to becoming, as a problem in being, an ...