- 113 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drawings of People by the Under-5s

About this book

This work traces the development of the human figure in children's drawings, showing how children add to and alter their figures as they get older and more skilful. It discusses why children's drawings often seem so bizarre to adults, revealing what these figures tell as about the child's Intelligence Or Emotional Stability.; The Book Is Based In Examples From hundreds of children, but concentrates on a particular set of drawings gathered from one group of children attending a nursery. Also featured are drawings by children with learning difficulties, so that readers may see and learn from the different developmental patterns in the drawing of human figures. Additionally, the book makes comparisons of drawings by children in different cultures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Drawings of People by the Under-5s by Dr Maureen V Cox,Maureen Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1

Scribbling

Although many nurseries can accommodate very young babies, most take children from about the age of 2 or 2 years 6 months. By this age most children have had at least some experience of using a pencil, crayons or felt-tipped pens. Of course, many children will still be scribbling and may not produce anything recognizable for quite some time. Unfortunately many parents and teachers seem to regard scribbling in a rather negative way. The educational psychologist Sir Cyril Burt (1921) thought of it largely in terms of motor movements without any particular purpose. This is a pity since, in fact, there is more to it than this and we may also see some development taking place within this scribbling ‘stage’. So, it is a mistake to dismiss it as ‘just scribbling’.

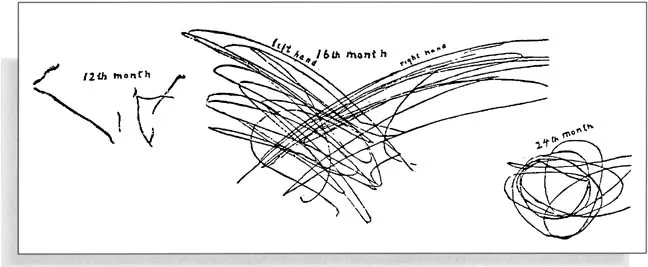

Like Cyril Burt, some other early writers (e.g., Bender, 1938; Harris, 1963) recognized that scribbling is an enjoyable activity for children primarily because of the rhythmic movement of the arm. As early as 1906, D.R. Major traced the development of scribbling in his son ‘R’. Around the time of his first birthday R would strike the paper with a pencil, a spoon or any similar implement, apparently in imitation of an adult's drawing or writing (see Figure 2). Gradually the arm movements became freer and the random disconnected lines produced with a pencil gave way to a more rhythmic left-to-right or back-and-forth motion of the hand, producing slightly curved lines with a loop at the end of each one. Those produced with the right hand dipped down towards the left and those with the left hand dipped down towards the right (see middle section of Figure 1). This swinging motion became more purposive and under good control by the time R was 18 months old.

From 18 months R began to add other movements: as well as horizontal lines often returning upon themselves he produced up-and-down and round-and-round scribbles (see scribble produced at 24 months in Figure 1). R's round-and-round scribbles became more controlled until he could produce an irregularly shaped figure bearing some resemblance to a circle or an oval.

Figure 1 Tentative stabs at the paper at 12 months of age give way to freer, rhythmic movements at 16 months. Round-and-round scribbles become more controlled by age 2 years.

Other researchers too have reported the increasing control that children manage to gain over the pencil and their ability to curtail their loopy or spiralling scribbles in order to form a roughly circular closed form (e.g., Bender, 1938; Piaget and Inhelder, 1956). This is important according to Rudolf Arnheim (1974) because the enclosed shape seems to suggest a figure against a background and opens up quite staggering possibilities of representation. By placing dots or scribbles within or outside the shape the child can represent important spatial relationships between objects or parts of an object. For example, a figure's eyes, nose and mouth can be contained within the boundary of the face. In Figure 23 two fish are contained within the boundary of the house in the centre of the picture.

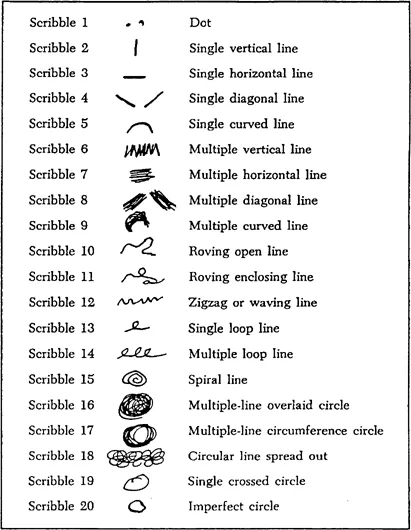

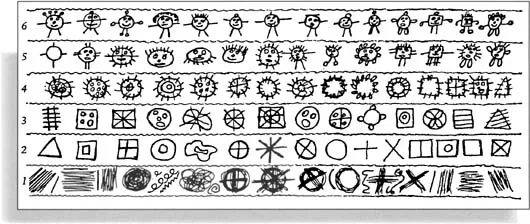

Rhoda Kellogg (1970) amassed a huge collection of children's scribbles and claimed to have discovered twenty different basic types, although each individual child doesn't necessarily produce all twenty of them (see Figure 2). She said that after practising these basic scribbles children then start to combine them and make more complicated forms. For example, they might draw a cross with two diagonal strokes; Kellogg called this a ‘diagram’. Framed inside a circle or a square it becomes a ‘combine’. A figure composed of three or more diagrams is an ‘aggregate’. These figures are elaborated into ‘mandalas’ (see level 3 of Figure 3). Then, at a later stage, ‘sun schemas’ appear – circular shapes and patterns with lines radiating from them (see level 4 of Figure 3). These sun schemas in turn are adapted, mainly with a face being added, and become the first representations of people. The idea, then, is of a progressive development from a repertoire of simple scribbles which are combined and recombined by the child into more complex patterns (see Figure 3). Although Rhoda Kellogg was careful to say that not all children necessarily go through all the steps in this process she none the less gave the impression of an orderly, step-by-step progression.

Now, we can sometimes see different kinds of scribbles used by different children in the nursery and one individual child may use a variety of types of scribble. But what evidence is there that the scribbles can be classified into twenty different types, as Rhoda Kellogg claimed? Well, the evidence is not very strong at all. Claire Golomb and Linda Whitaker tried to identify all these different scribbles (Golomb, 1981) in a study of 250 children. These researchers and their colleagues had great difficulty in agreeing with each other about the scribbles and, in the end, they could only agree on two main types: on the one hand, those which were circular, ‘loopy’ or included whirls and, on the other, those which involved repeated parallel lines. It seems to me that Claire Golomb and Linda Whitaker identified the two particular kinds of scribble described all those years ago by D.R. Major (1906) (see Figure 1).

Figure 2 (right) Twenty different basic scribbles identified by Rhoda Kellogg.

Figure 3 (bottom) According to Kellogg, basic scribbles are combined and recombined into more elaborate units.

In my own research I have found that after their earlier more exuberant scribbles some children may produce carefully controlled shapes and patterns along the lines described by Rhoda Kellogg, and this seems to indicate that they are gaining more skill at manipulating the pencil and are interested in experimenting with different shapes. But not all children necessarily do this; some simply go on filling the page with ‘sheer scribble’. So, it is not essential for children to produce the more carefully drawn shapes before they move on to representational drawing. In fact, although we tend to think of scribbling as a necessary early step in drawing there is no solid evidence that there would be a problem if children missed this experience altogether. And, indeed, there are examples of children in our own society and in others who have not had the opportunity to draw but later, when provided with pencil and paper, have produced recognizable figures often within the first half hour of experimenting with paper and pencil. This important observation was made by an anthropologist, Alexander Alland (1983), who visited a number of different cultures. What is particularly interesting is that the children's first encounters with the drawing materials were filmed so that there is a true record of their reactions and the actual process of drawing as well as the finished products. Alexander Alland found that there was not much evidence that the ‘milestones’ of early drawing development followed by western children occurred at similar ages in these other societies. Children did not necessarily draw the circles or mandalas claimed by Rhoda Kellogg to be universal. In fact, Alland came to the conclusion that the idea of a universal pattern of development in drawing has been much exaggerated.

Rhoda Kellogg believed that all children have an innate, aesthetic sense and that their scribbles reflect an urge to construct balanced, pleasing shapes; she claimed that children are not concerned with representing real objects, so their scribbles don't ‘stand for’ things in the real world. In fact, this is another aspect of her work which has been challenged. John Matthews (1984) has shown that children's scribbles sometimes are representational even if we adults don't recognize anything in them. He gives an example of Ben, aged 2 years 1 month, who made a series of overlapping loops on the page (see Plate 1, p. viii) and, while he was doing this, excitedly gave a running commentary: ‘…it's going round the corner. It's going round the corner. It's gone now’. Ben was probably describing the movement of an imaginary car going round the corner until it disappeared out of sight. So, Ben's scribble was not representational in the sense that it looked like a car; what he captured was the action or movement of the car. But this is representational; it has meaning and relates to something in the real world. It's not surprising, then, that John Matthews calls this sort of thing an ‘action representation’. We should be careful, however, not to get carried away and imagine that all scribbles are action representations. Often, when I asked my 2-year-old daughter about her pictures she would say, ‘I'm just scribbling’.

It's not clear from John Matthews' example whether Ben intended the car, or rather its movement, to be the subject of his picture before he began or whether he had already begun a spontaneous movement that then perhaps reminded him of a car. Sometimes when children are scribbling or experimenting with shapes they ‘see thi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Scribbling

- 2 Tadpole figures

- 3 The transitional figure

- 4 Drawing the body

- 5 Is there an orderly development?

- 6 Is development universal?

- 7 Adapting the conventional figure

- 8 Segmenting and threading

- 9 Gender in children' figures

- 10 Orientation of the figure

- 11 What can figure drawings tell us about a child' intelligence?

- 12 Children with an intellectual impairment or learning difficulties

- 13 Children with physical disabilities

- 14 Can drawings tell us about a child' personality or emotional stability?

- 15 Giving a helping hand

- Amelia Fysh

- References

- Index