eBook - ePub

Surviving the Early Years

The Importance of Early Intervention with Babies at Risk

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book considers the principal physical and psychological ideas and thoughts of what happens to parents from the moment they conceive. The discussion covers mothers who have become vulnerable due to "external" circumstances and provides different models to help overcome this process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Surviving the Early Years by Stella Acquarone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THOUGHTS IN SEARCH OF A THINKER

In the first three chapters, we consider a particular dialogue of emotions: the principal physical and psychological ideas and thoughts of what happens in parents from the moment they conceive.

CHAPTER ONE

The emotional dialogue: womb to walking

Much of the research literature over the past decades focuses on the infant’s cognitive and emotional development within the primary intersubjective dyad. In this chapter, I focus on the maternal perspective—the mother’s mental representations and her own emotional contribution to the primary relational system.

The way we mother is rarely our optimal choice. Women’s needs have changed dramatically over the past few decades, but a young baby’s needs have changed little over the millennia. In the west, educational parity and legislation grant women greater access to economic resources and higher occupational status. This creates new dilemmas and compromises for women, who realise that their ambitions and workplace demands are discordant with baby care. In Europe, some 12–20% of educated women decide to forego reproduction altogether. Facilitated by effective contraception or safe abortion, many young women delay childbearing in pursuit of a career, and some even decide to freeze their eggs. Pregnancy might occur naturally, but those whose fertility is compromised by postponement need assistance to conceive when the time feels right to have a child. On the other hand, earlier sexual activity and destigmatisation of non-marital births result in a high incidence of teenage pregnancies, and very young, often unsupported, single mothers.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy may be defined as an intertwining of three systems—physiological, emotional, and sociocultural. When first conception takes place within a stable couple, the period of transition to parenthood involves emotional upheaval. The partners’ twosome is reproducing a third. For the woman, two people now occupy one body—hers—which could be a bizarre and disturbing experience. Her external body image changes in response to visible alterations (the shape of her breasts and swelling belly), while internal configurations expand to include the newly occupied bodily cavity, new physiological symptoms, and a new organ—the placenta. Parameters of the couple’s previous relationships are destabilised with the pregnant woman’s greater vulnerability and dependence. As future co-parents, facets of their respective generative identities must be reformulated, and her self-image as expectant mother, worker, and lover changes. In addition, the couple’s sexual relationship is affected by bodily reappraisal and conceptualisation of the womb’s inhabitant, and their changed selves. While imminent parenthood draws some partners closer, for others, their divergent roles in gestating the baby might feel incongruous with previous equality, leading some women to feel privileged to carry the baby and others to feel resentful at having to do so. Similarly, in some couples, the man might feel grateful, while others might feel envious and deprived of this experience, leading to acrimony or even abandonment. Intimate partner aggression and direct foetal abuse are known to increase during pregnancy.

Many factors are involved in an expectant mother’s antenatal attachment to the baby, such as whether the conception was planned, wanted, and timely, and with the right impregnator. Pregnancy could be complicated by physical illness, disability, or multiple gestations. Sudden and incapacitating life events (such as bereavement, eviction, miscarriage, foetal diagnosis, etc.) or socio-economic problems (such as unemployment, poor housing, and poverty) can be devastating. Needless to say, the risk of antenatal as well as post natal emotional disturbance is elevated by a past psychiatric history or post traumatic stress disorder (TSD), but most studies stress the importance of current emotional support in boosting resilience in the face of adversity.

Previous perinatal experiences influence how this conception is perceived, as do unmourned reproductive losses from the past—her own or within her family of origin (Raphael-Leff, 1993). Similarly, fertility treatment and assisted conception, especially with donated gametes, can engender powerful fantasies and evoke feelings that the singularity of conception has been violated, which affect the internal dialogue with the foetus (Fine, 2014).

Antenatal emotional disturbance

In addition to the distress experienced by the suffering woman and her family, maternal disturbance during pregnancy has implications for the unborn child. In the mother, depression, paranoia, phobias, anxiety, and childhood abuse are associated with smoking, self-medication, recreational drug-taking, self-harm, and even suicide. Risk-taking behaviours and enactments have complex meanings, and could signify disregard for, or rejection of, an unwanted baby, or might challenge the baby to prove his/her capacity to withstand maternal failure. A pregnant woman’s state of mind, thus, has an indirect impact on the unborn baby through her behaviour.

We have long had evidence that emotional aversion to pregnancy and negative representation of the baby during pregnancy affect the postnatal mother-infant relationship, and predict insecure future attachment patterns (Fonagy et al., 1991; Raphael-Leff, 2011; Zeanah et al., 1994). Twenty to forty per cent of antenatally depressed mothers also report obsessional thoughts of harming the child. Maternal anxiety and PTSD (often linked to early emotional deprivation or childhood abuse of the expectant mother) indirectly affect the unborn baby through poor antenatal clinic attendance, unhealthy eating, or risk-taking during pregnancy—all of which are associated with interuterine growth retardation, smaller babies, and preterm delivery with long-term consequences.

The “foetal origins hypothesis” finds that the lower one’s weight at birth, the higher the risk for coronary heart disease, hypertension, stroke, type-2 diabetes, osteoporosis, and more fragile “homeostatic” settings in adulthood (Barker, 1999; Copper et al., 1996; Teixeira et al., 1999). Epidemiological studies suggest this might be attributable to increased uterine artery resistance index in the mother during pregnancy, with long-term effects on the child. Foetal under-nutrition has also been found to predispose men to depression in late adult life, suggesting a neuro-developmental aetiology of depression, possibly mediated by programming of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Interestingly, the odds ratios for depression among men, but not women, rise incrementally with decreasing birth weight (Thompson et al., 2001).

Although long considered an “old wives’ tale”, research findings now suggest that maternal emotions have a direct effect on the gestating foetus. Emotion can be as toxic as alcohol, nicotine, and opiates imbibed by the mother. Exposure in the womb to chronic maternal stress has been linked in later life with depression, hypertension, psychosis, hyperactivity, and alcoholism, possibly resulting from damage due to prolonged activation of brain opiates during gestation.

A growing body of work finds that maternal distress in pregnancy is associated with later behavioural problems in the offspring. Antenatal as well as postpartum maternal stress are correlated with the temperament of their three-year-olds (Susman et al., 2001). One longitudinal study of over 10,000 women isolated antenatal from post natal disturbance, finding that anxiety in late pregnancy posed an independent risk associated with behavioural/emotional problems into pre-adolescence (O’Connor et al., 2005).

The mechanism of transfer is unclear, but it is postulated that emotion has an impact through associated biochemical and physiological transmission. Foetal cerebral circulation is affected by maternal anxiety (Sjöström et al., 1997) through high cortisol levels, which, when transmitted to the foetus, increase the baby’s hyper-reactivity (Wadha et al., 1993). Obstetric complications are also associated with both heightened maternal anxiety and perinatal distress.

Clearly, as prophylactic treatment is indicated, midwives, health visitors, and other perinatal practitioners are in a prime position to identify distress and refer women for psychotherapy, ideally during pregnancy. But what does such “distress” consist of?

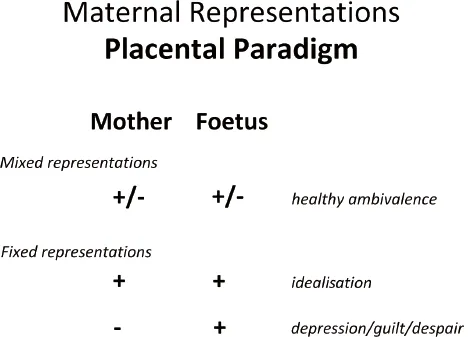

Placental paradigm

Depending on the “emotional climate” of her inner world, a pregnant woman views her inmate as vulnerable or thriving, damaged or demanding, perfect or potentially harmful (Figure 1.1). Concurrently, she might see herself as bountiful or deficient, hospitable or invaded. Accordingly, their emotional connection is deemed reciprocal, while at other times it feels asymmetrical, incongruous, or antithetical, a one-way process that privileges either herself (as generous, withholding, or exploited), or focuses on the baby (as greedy, or needy, malevolent or benign, etc.). Depending on her own psycho-history, current mood, physical condition, and the baby’s movements, one pregnant woman may oscillate several times a day, alternating between both positive and negative fantasies, while another maintains a “fixed” idea of the primal interchange.

Thus, one pregnant woman might experience the give-and-take between herself and her unknown baby as a pleasurable communion, while another is filled with a sense of alarm at the foetus pumping waste into her. Endangered by the foetus leaching her internal resources, an expectant mother might be unable to stop binging or smoking to assuage her escalating anxiety. Another feels guilt-ridden, believing she is insufficiently nurturing to sustain the pregnancy or produce a normal, viable baby. Experiencing persecutory feelings of invasion or dissipation and exploitation, yet another resorts to retaliatory behaviour, such as bashing or starving the “parasitic” foetus.

Clearly, her personal stance, with its underpinning mental configuration, reflects a woman’s self-esteem and generative psycho-history (including previous miscarriages or abortions, painful experiences of disappointment or betrayal, or happy ones of love and trust). A woman with a robust sense of self, who has self-reflectively come to terms with her own parents’ human fallibility, will be resilient enough to tolerate the discomforts and risks of pregnancy through trust in her own “good-enoughness” now, and as mother to a less-than-perfect future baby.

Observations of non-clinical groups (for instance, childbirth education classes and community samples) indicate that pregnant women who are confident in their capacities and more secure in their attachments experience a rich mixture of feelings and fantasies. These vary throughout their daily activities in response to social contacts, physiological triggers, foetal movements, daydreams, and other experiential stimuli.

This attitude of healthy ambivalence enables an expectant mother to accept the uncertainties of gestation and the hardships of parenthood, including inevitable changes in lifestyle, as well as the many joys (and losses) motherhood will bring. Such a flexible approach allows an expectant mother to play with a variety of daydream scenarios about her unknown baby and herself as a mother, during the course of which further digestive processing of her own childhood experiences occurs. However, maintaining a “fixed” idea of pregnancy and the foetus, whether positive or negative, reduces the likelihood of emotional elasticity and “working through”.

Preconscious mental representations of parenting are complex, multi-layered, and variable. Clinical experience with women or couples (often beginning months or even years before conception occurs, and continuing well into parenthood) indicates that a person’s mental representations of him/herself as carer are multi-determined. Imagery consists of a composite schema related to one’s own emotional experience (or “internal model”) of being parented. Childhood events and recollections of early care mingle with subsequent encounters with nurturing or rejecting others. Adult expectations, hopes, and conscious wishes join less conscious configurations, including identifications with the baby, and with past carers and/or aggressors.

However, in addition to such residues, during the emotional upheaval of pregnancy and early motherhood, unresolved past issues are powerfully reactivated.

“Contagious arousal”

For all of us, our sense of self is constituted through reflective mirroring (Winnicott, 1967), and “affective biofeedback” provided by sensitive carers (Gergely & Watson, 1996), which forms the basis of our capacity for our understanding of mental states in ourselves and others (Fonagy et al., 1991). Such parental “mentalization” echoes the “metabolisation” of acute preverbal anxieties, which paves the way to internalisation of a capacity for self-containment (Bion, 1962). Parenting revives this procedural experience with an intensity that relates to intentional and unwitting “messages”, including projective distortions. Emotional understanding is also composed of residues of the archaic carer’s own unconscious sense of self—as mother, sexual woman, and agential person—in the world beyond domesticity. All this might or might not have been processed along the way, both by the original carer and the current (expectant) mother whose composite representations of motherhood also reflect imagery of her own baby-self in the mind of her archaic primary carers, thus replicating the emotional climate of her own pri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- About the Editor and Contributors

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part I: Thoughts in Search of a Thinker

- Part II: Reaching the Vulnerable at Risk from “External” Circumstances

- Part III: Vulnerable Groups Coming from “Internal” Fragile Circumstances

- Conclusion

- Index